There is a conundrum at the heart of European-Caspian energy relations: the politics are nearly in place, but project deliverability is not. Europe wants to secure substantial volumes of gas from Azerbaijan but, although Baku says it is making progress on plans to develop the fields necessary to meet longer-term targets for European exports, it risks being too late to help out because of long project timelines. Where the politics are not in place is that Turkmenistan, the only Caspian source that could help Europe access the additional gas it needs in 2023-24, remains unwilling to engage in the kind of discussions that would help it contribute to Europe’s requirement for immediate gas supplies.

The key issues are: timings for Europe’s requirement for additional imports (now); the requirements for infrastructure to carry these imports (now); and the timings for potential increases in Azerbaijani supplies (unclear). Then there are the terms under which Turkmenistan might consider exports across the Caspian; Turkey’s role as a potential market; and whether deliveries to the European Union should focus on the Balkans, rather than Italy.

Gas market fundamentals in Europe and Azerbaijan

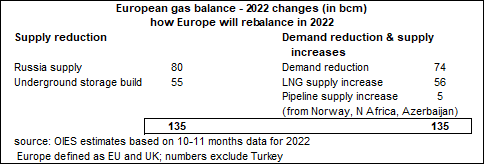

The underlying market context is how countries are managing their gas balances. The table below examines how Europe has rebalanced while losing around 80 billion cubic meters (bcm) of Russian supply:

Additionally, storage has been rebuilt, which in effect means parking current supply for tomorrow’s demand. On the other side of the rebalancing sheet, the principal components are falling demand and liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports. Pipeline imports increased only marginally. Interestingly, the 74 bcm demand fall is very close to the 15 percent reduction targeted by the EU Commission, and achieved through reaction to high prices, not government decree.

Europe has been lucky. Asia has taken less LNG and November was warm. EU total storage capacity in November was 95 percent full; by the end of November it had hardly moved, down to 94 percent. In effect, Mother Nature gave Europe a whole storage month.

Next year will be harder. There will be a full year of reduced (possibly zeroed-out) Russian gas, Asian LNG demand might return, storage will need to be rebuilt, and it might get cold in Q1 2023.

The Commission has spent considerable effort touring pipeline-exporting countries, like Norway, Algeria, and Azerbaijan, in search of more supply. In July, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and Energy Commissioner Kadri Simson were in Baku and came back with a memorandum of understanding (MOU) on expansion of the Southern Gas Corridor for more gas—from 12 billion cubic meters per year (bcma) to 20 bcma by 2027.

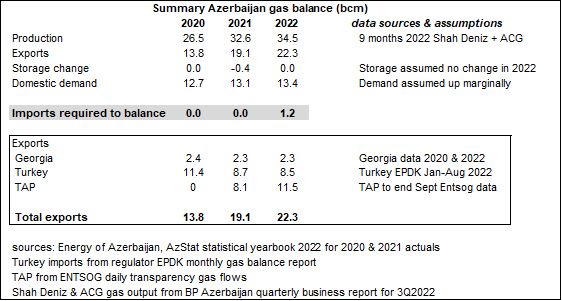

The other part of the equation is Azerbaijan. The table below sets the scene:

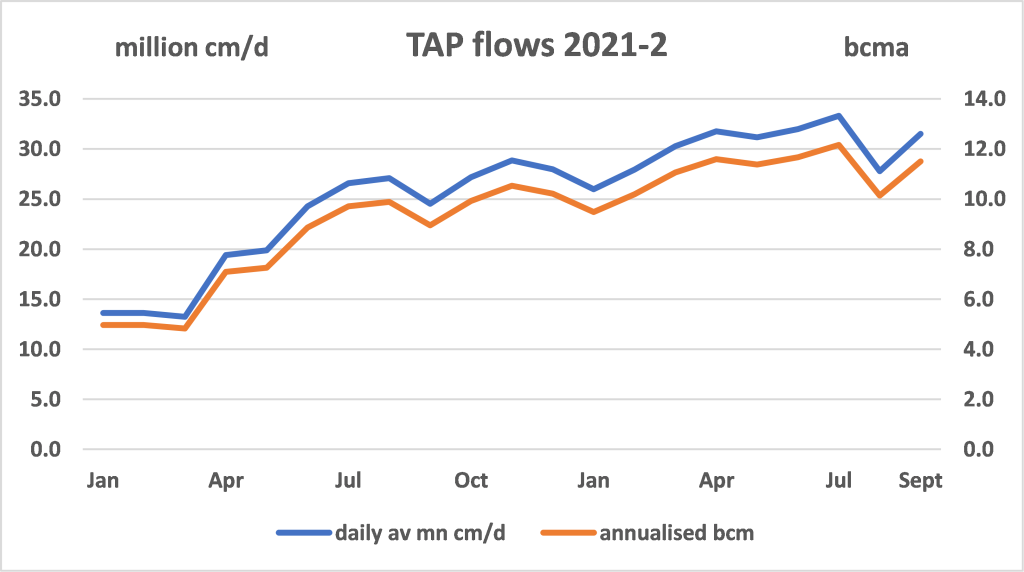

With Shah Deniz nearing full production now, Azerbaijani output will be up 5-6 percent in 2022. Exports will be up too, roughly unchanged to Turkey but up for Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) markets Italy, Greece, and Bulgaria. Energy Minister Shahbazov recently talked about 11.5 bcm to Europe, and this looks realistic. Note, TAP volumes recently have been at 12 bcma.

With reasonable expectations of a small rise in domestic demand and unchanged underground storage levels, Azerbaijan needs imports to balance.

In January 2022, a scheme involving Turkmenistan’s gas exports to Azerbaijan via an Iran 1-2 bcma swap started. Then in November came disclosure that Russia would supply Azerbaijan with 1 bcm between November and March. Exact volumes flowing have not been reported, but the balance above suggests at least 1.2 bcm is needed in 2022. A cynical view would be that Azerbaijan has successfully maneuvered to buy in gas at one price and sell it spot at high European prices.

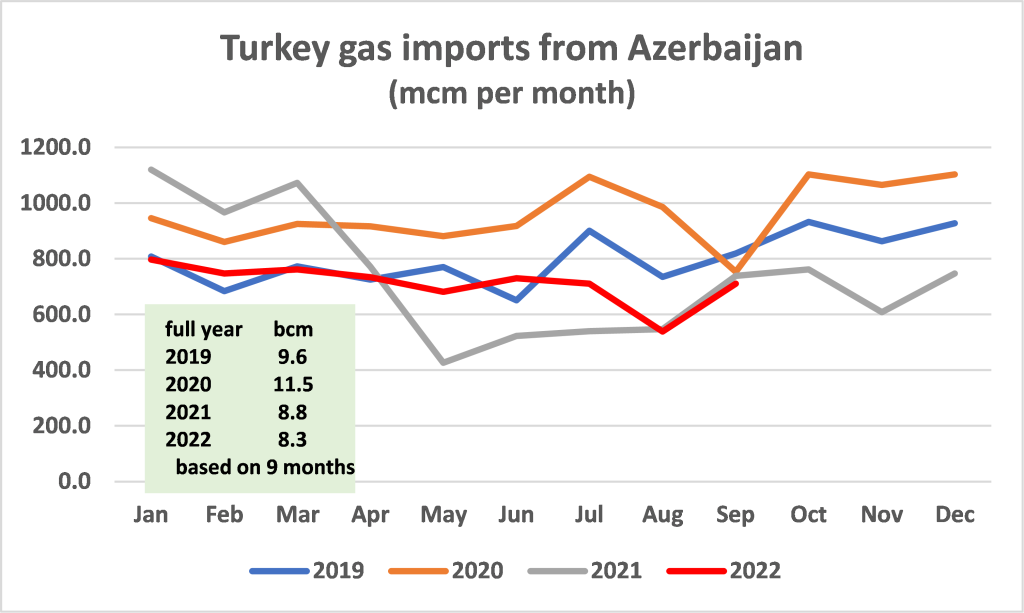

Meanwhile, Azerbaijani gas exports to Turkey remain down from the 2020 level of 11.5 bcm as a result of only a partial renewal of the Shah Deniz Stage 1 contract, with Azerbaijan preferring to retain some volumes for export flexibility. While commercially this makes sense, it may not politically. In an election year in 2023, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan will want to ensure maximum gas flows this winter, and Ankara is pressing Baku for an extra 10 bcm.

Erdogan is scheduled to hold tripartite talks with Turkmenistan’s President Berdimukhammedov and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev on December 14. According to a Bloomberg report on December 9, senior Turkish officials have said Erdogan would revive the idea of shipping Turkmen natural gas to Azerbaijan for subsequent insertion to the SGC. Almost certainly, the Turkish idea is based on using compressed natural gas (CNG) for the shipments, which would require construction of compression facilities and either specialized tankers or specialized storage cylinders for loading onto barges. In 2010, the International Energy Agency estimated it would likely cost around $1.40 to $2.00 per MBtu to ship 5 bcma of CNG across the Caspian, compared to costs of around $0.70 to $0.80 for/MBtu for gas transported by pipeline. Commercial sources in Ashgabat told one of the authors at that time they considered CNG transport would be roughly four times as expensive as pipeline gas. The authors regard a CNG Trans-Caspian value chain as being a non-starter.

Azerbaijan is therefore in a curious position. As a major gas producer, it has signed an MOU to carry more gas from Baku to Europe but lacks a clear path to providing all or most of the necessary input itself. Meanwhile, it has to import gas from Turkmenistan via Iran and Russia to help it meet its domestic and export commitments. And while Apsheron Stage 1 should come on-stream in 2023, its 1.5 bcma output is already earmarked for the domestic market.

The key issues

a.) Infrastructure and production requirements

Some sections of the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC) can currently handle a little more gas. There is perhaps 4-5 bcma of spare capacity on the sections from Azerbaijan to Turkey, but precious little thereafter. The EU-Azerbaijan MOU of July 2022 to take exports from the current 12 bcma to 20 bcma will require investment in compressors and, perhaps, some parallel pipelining (looping). The costs remain unknown but can be reckoned in billions of dollars or euros. TAP has already announced market test plans for 2023 to see whether suppliers are prepared to commit volumes for throughput that would justify the expansion costs.

On production, Azerbaijan has a long list of potential offshore gas developments: Apsheron, ACG Deep, Shah Deniz Stage 3, Shafag Asiman, and Socar’s Umid/Babek. At present, the only ones actually proceeding are Socar’s own Umid block, which is already producing at around 1-2 bcma, and the 1.5 bcma Apsheron Stage 1, although Socar sources say that discussions with Apsheron’s operator, France’s Total, for full field agreement are very close to completion and that an agreement could be concluded early in 2023. If so, this should add 3 bcma to Azerbaijani export-focused output in or around 2026.

All the others require either further exploration or a development plan and project commitment—in other words, a final investment decision (FID). Eventually—there is no clear timeframe—Socar hopes to produce up to 5 bcma from its Babek field while Socar sources say discussions on ACG Deep are “on track” and that the field, considered capable of producing up to 5 bcma, could start to come on stream in 2027-28. bp, the operator, is engaged in discussions with Socar on enhancing production at Shah Deniz, but there is no indication concerning either the volumes or timeframe for any increase in output.

b.) Timeframe

Getting a project ready for FID requires planning, engineering, project finance, commercial gas sale agreements, and contracts for platform construction and local infrastructure as well as for SGC pipeline expansion. Unless this process is already well under way, there is no hope for any additional export-oriented production from Azerbaijan for the next 4-5 years.

c.) Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan does have gas available. It can supply gas both to help Europe meet its urgent requirements for gas in 2023-24 and to cover any shortfall in Azerbaijani gas supply for an expanded SGC. Although the current swap via Iran demonstrates that gas from Turkmenistan can already reach Azerbaijan by pipeline, either directly or indirectly, lack of transparency and a 3 bcma limit to Iranian pipeline capacity render it almost irrelevant in the context of European supply.

That places the focus on a trans-Caspian pipeline, a subject raised by Baku in countless talks with Ashgabat. The problem is the near-total mismatch between European requirements and Turkmenistan’s aspirations. Europe wants gas now. In technical terms, this could be accomplished in relatively short order, such as through the Trans Caspian Connector project. This would link Turkmenistan’s and Azerbaijan’s offshore facilities with a 78-km pipeline, and could be put in place at an estimated cost of around $400-600 million within a few months of securing the necessary approvals of both countries and the necessary financing.

However, Turkmenistan has informed US diplomats that it is not interested in the Connector project and is signaling that it won’t get out of bed for anything less than the decades-old idea of a 30 bcma pipeline. Building such a line, and more importantly arranging the onward transportation and sales in Turkey and EU, would be far more complicated than a simple connector. A new 30 bcma system from Turkmenistan to Italy, roughly twice the size of the SGC, would cost vastly more than the $20 billion required for the SGC’s initial pipeline components.

Moreover, Turkmenistan would probably demand a long-term contract structure which the EU itself cannot provide, and which European companies might be reluctant to sign. Overall, nothing could be completed before 2030, by which time the EU should have resolved its current supply crisis and be far along the path to a renewables-based energy future.

d.) The role of Turkey

Turkey’s gas demand is soaring, amounting to 46.2 bcm in 2020, 57.3 bcm in 2021, and roughly the same in 2022. It wants more Azerbaijani gas and would also like gas from Turkmenistan in its supply portfolio. But Turkey is already a highly competitive market with multiple pipeline supply options from Russia (Blue Stream, Turk Stream), Iran, and Azerbaijan, while LNG routinely accounts for around 25-30 percent of all imports.

Moreover, while imports currently account for 99 percent of supply, it is developing its giant Sakarya field in the Black Sea, discovered in 2020, with first gas expected in March 2023, well in time for both the presidential election next June and for the centenary of the Republic next October. The build-up to planned 15-bcma plateau production in 2027 appears quite realistic. So the landscape for a Caspian producer looking at Turkey is becoming ever more competitive.

e.) The Balkans and the Trans Balkan Pipeline

Expansion of the SGC may well involve more than simply expanding the SGC, notably the addition of substantial new capacity to carry gas to demand centers in Northern Italy. When the SGC FIDs were signed in late 2013, Italy was importing around 7 bcma from Algeria and there was spare capacity for the system to accept gas from TAP. But Italian imports from Algeria are now running at around 21 bcma. Azerbaijan clearly worries that any expansion of SGC’s TAP section needs to be accompanied by several hundred kilometers of expensive new pipeline infrastructure within Italy.

There are alternatives. All the Russian gas which once flowed down the Trans Balkan pipeline system through Romania or Bulgaria and then to Greece, North Macedonia, and Turkey has, since January 2020, been diverted into Russia’s Turk Stream pipeline. So the 20-25 bcma Trans Balkan System is now only partially used. For instance, it currently carries around 2 bcma of Russian gas in reverse-flow mode from Turk Stream via Bulgaria to Romania. Using it as an alternative or complementary route to TAP is possible, although this would involve new marketing arrangements if substantial amounts of Caspian gas, for example the 8 bcm noted in the EU-Azerbaijan MOU talks in July, were involved.

Conclusion

Azerbaijan has no production projects that can deliver extra gas to Europe right now, and its strictly limited output prospects mean that if wants to inject as much as 8 bcma into an expanded SGC by 2027, then work, not talk, needs to start today.

Turkmenistan constitutes the only immediate source for new Caspian gas supplies in 2023. But while this could be inserted into a small but straightforward connector, and is backed by Azerbaijan, such an approach is rejected by Turkmenistan, which is waiting for Europe to come along with money and a long-term contract for 30 bcma. That simply will not happen.

On November 25, Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliev delivered the most pertinent summary of the current impasse. Asked by one of the writers of this piece about the status of discussions on a trans-Caspian Pipeline, Aliyev said it was up to Turkmenistan: “They have to make a decision. They want us to do it. They will have to take some action. We will not initiate action.”

John Roberts is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center and a member of the UN Economic Commission for Europe’s Group of Experts on Gas.

Julian Bowden is a former economist with BP specializing in gas markets in SE Europe and the Caspian, and is a Senior Visiting Research Fellow with the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies OIES.

The authors acknowledge that they are on the advisory board of a project to lay a 78-kilometer connector pipeline between the Petronas-operated Magtymguly field in Turkmenistan and gas-gathering facilities operated by BP in the Azerbaijan’s Azeri-Chirag-Gunashli oilfield.

Related content

Learn more about the Global Energy Center

The Global Energy Center develops and promotes pragmatic and nonpartisan policy solutions designed to advance global energy security, enhance economic opportunity, and accelerate pathways to net-zero emissions.

Image: Utility meters. (Doris Morgan, Unsplash, Unsplash License) https://unsplash.com/license