How WhatsApp upended Middle East diplomacy—and what the US can learn from it

The pandemic suspended life around the world. As travel and in-person engagement became taboo amid shelter-in-place decrees, governments, like all other businesses, have had to adapt to a new normal, propelling new virtualization and informalization of negotiations between leaders. This coincided and reinforced a major geopolitical shift: the diplomatic efforts leading to the signing of the Abraham Accords between Israel and three Arab countries.

Over the past few years, WhatsApp, the cross-border bridge-building tool used by over two billion users globally, has become a successful out-of-the-box and entrepreneurial tool of statesmanship, leveraging the privacy of direct leader-to-leader engagement and policy-hobnobbing to alter the pathway for regional peacebuilding and negotiations in the region.

“WhatsApp diplomacy” has become the de facto tool for facilitating traditional communications-based diplomatic practices and is now defining inter- and intra-state engagement between government officials around the world—particularly in the Middle East. The physical constraints imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated its use in facilitating multilateral and bilateral engagements, making WhatsApp—as well as its messaging app peers Signal and Telegram—now central to the personal forms of communication that influence how world leaders and their governments engage with each other.

In WhatsApp’s encrypted channels, diplomats feel freer to form and participate in groups where they privately share resources, coordinate meetings, strategize with colleagues, create informal alliances, lobby for their country’s positions, and coordinate policy decisions. The development of personal relationships between officials via WhatsApp allows for discretion in negotiations, which offers an immediate alternative to old-school practices, such as leaving the room to “chat outside,” for the majority of the time when foreign officials are not together.

In 2023, the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) acknowledged the use of WhatsApp by British diplomats, including former Secretary of State Dominic Raab, to conduct official business in place of government-encrypted communications platforms. Under the 2019-2022 Boris Johnson administration, WhatsApp exchanges increasingly supplanted email threads and formal meetings during peak COVID times, concentrating much of Whitehall’s decision-making processes on the app.

WhatsApp is upending relationships in the Middle East

In places like the Middle East, where WhatsApp is one of the dominant platforms for day-to-day communications, there is a strong and growing reliance on the messaging app to engage foreign government leaders. In the Gulf—where society and leaders value deep and personal relationships based on an established trust—WhatsApp is playing a significant role in building professional ties with other governments. Perhaps best and most notably exemplified within the Donald Trump administration, President Trump and then senior White House Advisor Jared Kushner invested significant time and effort into cultivating a strong rapport with Gulf leaders via instant messaging apps.

Kushner built personal and strategic relationships with Emirati and Saudi leaders through WhatsApp, helping to enable closer engagement and leading to critical foreign policy successes, including, most prominently, the 2020 Abraham Accords. Since leaving the White House, Kushner has retained access to these relationships, using them to lock in a $2 billion investment from the Saudi government’s sovereign wealth fund for his new private equity firm.

More recently, the Negev Summit organized in Sde Boker, Israel, in March 2022—which was the first-ever multilateral Arab-Israeli summit of foreign ministers—came together in a matter of days at the initiative of then-Israeli Foreign Minister Yair Lapid via a series of WhatsApp conversations with his Arab and US counterparts. These personal connections effectively cut out a multitude of bureaucratic layers to great success. The summit represented a pivotal shift toward warm peace, Israel’s integration into the region, and support for increased multilateral cooperation, establishing an annual meeting of foreign ministers from the member countries, as well as six working groups to advance transregional initiatives on an array of issues, including food and water security and clean energy.

New forms of communication mean new risks

The use of WhatsApp or similar platforms for diplomatic purposes is not without concern. Most pressingly, there are questions around the adequacy of its security capabilities regarding sensitive discussions between government officials and its lack of formal integration within diplomatic processes. Despite the adoption of end-to-end encryption, WhatsApp continues to collect information, including device information, IP addresses, profile names and pictures, and usage information, which it shares with other Meta-owned companies, including Facebook—a social networking site notorious for its privacy and data scandals.

Other questions of digital diplomacy, such as adequate data security and legality issues, present a challenge. In 2023, the US Supreme Court permitted WhatsApp’s parent company to pursue a lawsuit against NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware activities—following a lost appeal from NSO claiming foreign sovereign immunity—on behalf of unidentified foreign governments. NSO Group, now blacklisted by the Biden administration, was reported to have exploited a bug in WhatsApp to install spy software and conduct surveillance across sectors and dissidents.

“Government by WhatsApp” also underscores clear challenges to public record keeping and transparency when officials use these messaging apps for sensitive exchanges on personal or government-issued devices and accounts. This includes using automatic deletion (e.g. WhatsApp’s ‘disappearing messages’ functionality) to expunge a record of exchanges. A more pragmatic issue also relates to the exclusionary nature of WhatsApp groups and the capacity for policy decisions made during chat exchanges to be effectively acted upon through state bureaucracies.

Safe reliance on digital diplomacy, therefore, necessitates steps to address the legal parameters of using non-governmental communications platforms and establishing clear guidelines for sanctioned use. Countries like the United Kingdom have already taken steps to outline official guidelines on the use of WhatsApp for government business. Beyond that, messaging apps must be more clearly and effectively integrated into existing bureaucratic processes to guarantee solid follow-up and implementation across all levers of government.

While there is the possibility that such regulation could deter the use of these apps for direct coordination between policymakers, it would ensure necessary transparency in inter- and intra- government engagement. Such communications should be covered by the US Freedom of Information Act, Presidential Records Act, and Federal Records Act, just like email and other types of official government communication.

Encryption-enabled communications serve the public and national security, but privacy must be balanced and should be able to co-exist with public disclosure laws as needed.

Some branches of the US government have already begun to make the transition. The US Department of Defense and US Customs and Border Protection have recently purchased licenses for AWS’s encrypted messaging app, Wickr, which provides e-technology discovery and unlimited data retention, therefore, allowing the collection of electronically stored information in case of a lawsuit or investigation.

New tech can help governments better deliver services, conduct diplomacy, and quickly pivot to a virtual footing. The US government should start thinking beyond the methods by which services can be delivered and focus instead on what types of services can be delivered through a digital platform that supports the standardization of a verified WhatsApp account or an official US government app that emulates WhatsApp’s features. US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) urgently needs new service delivery models and enhanced communication channels with the public, and a future US government app modeled after WhatsApp could connect high-fee-paying customers experiencing emergencies with a USCIS immigration officer instead of a chat bot or contractor unable to make any decisions. At the State Department, standardizing the practice could provide its backlogged consular affairs department with a new method to communicate directly with people applying for visas overseas.

WhatsApp diplomacy offers a new model to fill public sector gaps and cut across red tape. Taking heed of lessons from similar pursuits in other countries, the US government can do more to create and embrace more agile responses to the people it serves and be able to balance privacy and transparency. It is challenging times like today where governments need further agility, collaboration, and creativity. The WhatsApp revolution and the rise of AI tools are undoubtedly models that can be attuned and molded to our specific needs.

Joze Pelayo is an assistant director at the Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative/Middle East Programs. Follow him on Twitter: @jozemrpelayo.

Yulia Shalomov is an associate director with the N7 Initiative in Middle East programs, where she supports the Center’s work on Israel.

Further reading

Thu, Jan 26, 2023

People-to-people exchanges matter. They’re integral to nurturing the Abraham Accords.

MENASource By Richard LeBaron

This piece identifies some of the issues involved in creating a strong framework for a vital “Abraham Exchanges” program and proposes a few ideas on how to get it off the ground.

Thu, Dec 15, 2022

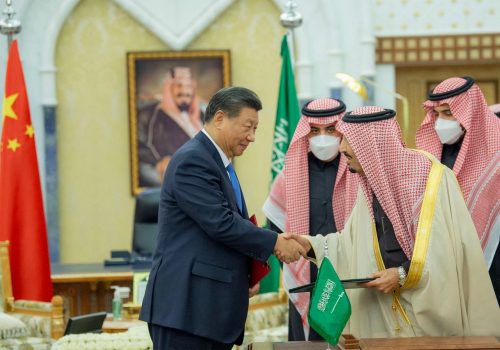

No, Xi’s visit to Riyadh wasn’t because of bad US-Saudi relations. It’s about much more.

MENASource By Jonathan Fulton

Given the bad state of US-Saudi relations, it is natural to see Xi’s visit in the context of geopolitical competition between Washington and Beijing, but that framework misses the bigger picture.

Thu, Apr 15, 2021

Baby bottle coffee drinks and censorship: The ultimate guide to Arab TikTok

MENASource By Samantha Treiman

Although TikTok provides a platform for creative expression and political speech, repressive governments around the world attempt to censor users—and the Middle East is no exception. Those in charge are fearful of the app’s quick-sharing nature, which can allow anything from popular dances to government slander to spread rapidly.

Image: White House senior advisor Jared Kushner (C) arrives to join U.S. President Donald Trump and the rest of the U.S. delegation to meet with Saudi Arabia's King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud at the Royal Court in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia May 20, 2017. REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst