Saudi Arabia and Qatar are cooperating with the Taliban. But their approaches to Afghanistan are different.

Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) members, like Saudi Arabia and Qatar, have high stakes in post-occupation Afghanistan. From the potential for international terrorist organizations—such as the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP)—to exploit the country’s security vacuum to the deteriorating humanitarian conditions of the Afghan people, Afghan troubles pose direct and indirect security threats to Gulf Arab states.

Although no government worldwide has yet to formalize diplomatic relations with the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, Gulf Arab governments are, to various extents, cautiously moving down a path toward soft normalization or partial recognition of the Taliban regime.

All GCC states have come to terms with the reality of Taliban rule in Afghanistan since August 2021 and must pragmatically deal with the situation on the ground. Saudi Arabia and Qatar see Afghanistan primarily as a security and humanitarian concern, however, their approaches toward the country differ. Under Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman (MBS), they have changed to a more humanitarian-based approach, using their sway in major Islamic institutions to funnel aid to the Afghan people. Qatar also started to play a more visible, leading role in Afghanistan roughly a decade ago, but has achieved much considering its relatively small size. It facilitated the US-Taliban talks that led to the 2020 Doha Agreement and played a valuable role in evacuating thousands of foreign troops and civilians out of Afghanistan in mid-2021.

The twists and turns of Saudi Afghan policy

Security concerns have been the central theme for Saudi engagement with Afghanistan, though the kingdom’s pursuit of different goals depending on the historical context reflects a continuous evolution of its strategic priorities. After the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979, Saudi Arabia presented itself as a barrier to the atheist claims of the communists. The country then worked to contain the ambitions of the Islamic Republic of Iran in Greater Central Asia, before pivoting again to become a bulwark of religious tolerance against radical terrorist ideologies, such as al-Qaeda’s, after September 11, 2001.

The abrupt shifts in Saudi’s Afghan policy speak of a foreign policy approach that is highly reactive to the country’s changing strategic priorities. This ultimately contributed to undermining the credibility of the Saudis in the eyes of the Afghan public, and their reputation reached an all-time low in the early 2010s. Mindful of the decades-long meddling in the country’s affairs, large swaths of the Afghan political spectrum grew distrustful of Saudi Arabia’s ambitions, and the kingdom was relegated to the sidelines of Afghan politics.

Saudi Arabia resumed engagement with Afghanistan in the wake of MBS’s nomination as crown prince in 2017 (a redefinition of the kingdom’s succession line also marked policy changes). In Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia has pursued a semi-open anti-Taliban policy, distancing itself from its former partner by contrasting the group’s radical version of Islam with its more “moderate Islam.” In July 2017, for example, Saudi Arabia hosted a two-day international conference of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), promoting peace and stability in the war-torn country. More than one hundred religious scholars from nearly forty countries participated in the event, which concluded with a declaration condemning the religious illegitimacy of violence perpetuated by the Taliban—a group that has yet to be formally recognized by any government.

The kingdom continues to leverage its still-relevant leadership credentials through Islamic intergovernmental organizations, such as the OIC and the Islamic Development Bank (IsDB), to pursue its national interests abroad. Reluctant to directly engage with the Taliban and short of contacts on the ground, Saudi Arabia found two valuable conduits in the OIC and IsDB to safely gain a foothold in Afghanistan. Against the backdrop of the Taliban takeover in mid-August 2021, Saudi Arabia has played a pivotal role in pressuring OIC and IsDB members to facilitate the provision of humanitarian assistance to the country. Moved by the aim of providing relief to the battered Afghan population, the IsDB approved the establishment of the Afghanistan Humanitarian Trust Fund in February 2022. In March 2022, the OIC appointed a new director general to its office in Kabul and the OIC Mission was officially inaugurated in mid-November 2022. High-ranking Taliban officials, such as the Afghan Acting Foreign Affairs Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi, and representatives from prominent international organizations, were present at the opening ceremony.

Despite recent successes, Afghanistan still evokes bitter memories in Saudi Arabia. Fearful of the potential reputational costs of engaging with the Taliban, Riyadh has been careful to gear its actions toward humanitarian goals and solidly ground them within an institutional framework. Confident of its well-regarded leadership role within OIC and IsDB, Riyadh has sought to pursue its Afghan policy through a “leading from behind” approach.

Qatar’s niche Afghan diplomacy in a nutshell

In roughly a decade of engagement in Afghanistan, Qatar has made remarkable strides in building sound diplomatic credentials at regional and global levels. By offering its intermediation services to third parties seeking an entry point in the Afghan complex, Doha went from a newbie to a trendsetter in the Middle East power game. With much less political baggage than other Arab Gulf states, Qatar saw Afghanistan as a springboard to promote its niche diplomacy. It facilitated the US-Taliban talks that led to the 2020 Doha Agreement and was critical in evacuation operations, airlifting thousands of foreign troops and civilians out of Afghanistan in mid-2021.

However, protracted diplomatic activism comes with strings attached. Qatar now has its fair share of problems linked to Afghanistan and has partially lost its untainted image as a neutral third party among some segments of the Afghan population. One of the first things Qatar did to gain some clout was to permit the Taliban to open a political office in Doha in 2013. Hampered by a United Nations (UN) visa ban and the UN General Assembly’s rejection of the Islamist regime’s request to have one of its ambassadors take over the country’s seat at the UN, the Taliban still rely heavily on the Doha political office to conduct diplomatic activities outside of Afghanistan. However, the Taliban, which has a long track record of simultaneously courting different partners and playing them against each other to extract concessions, has told Doha that they are exploring alternatives.

The meeting that took place in Abu Dhabi in early December 2022 between Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan—United Arab Emirates (UAE) president and emir of Abu Dhabi—and Mullah Mohammad Yaqoob—Afghanistan’s acting defense minister—highlighted the Taliban’s mounting commitment to broaden the number of facilitators beyond Qatar and Pakistan. With an Abu Dhabi-based company winning three bids to run operations at the main Afghan airports, the UAE has come to play a more visible role in the country during the past months. After years of strained relations, UAE-Qatar ties have improved recently, with UAE-Qatar leaders speaking of a shared desire for appeasement rather than confrontation. Just a day after his meeting with the top Taliban security figure, Sheikh Mohammed paid an official visit to Qatar’s Emir, Sheikh Tamim bin Jassim Al Thani, demonstrating that Afghanistan could offer the conditions to bring further rapprochement between Abu Dhabi and Doha.

Qatar’s Afghan policy yielded mixed results. On the one hand, it significantly helped Doha cement its status as an ascendant regional power and reputation as a reliable partner for the US and Europe. On the other hand, it highlighted the structural constraints hindering Doha’s ambitions to emerge as regional grand mediator. Qatar was unable to pressure the Taliban into making meaningful concessions while the Taliban took back Kabul and got the US to withdraw its troops. Whether the sound diplomatic capital Qatar built in Afghanistan over a decade will continue to pay dividends mostly depends on Doha’s capacity to retain its status as an all-weather mediator.

Cooperation over competition

Radical ideologies plague Afghanistan and its strategic geographic position in the heartland of Central Asia means that any troubles the country faces become regional and international concerns. From the 1979 Soviet invasion to the 2001 US invasion, history shows that armed escalation has knock-on effects that resonate well beyond Afghanistan. From a foreign policy perspective, the Afghan dilemma cannot be solved by one country alone. Past experiences show that exploiting Afghanistan’s security and political vacuums to settle old scores have led to devastating outcomes whose long-term consequences still resonate today.

As long as Afghanistan remains under the Taliban’s control, Gulf countries must determine to what extent they should engage with the Islamist regime. While there is no clear answer to that question, a loosely-defined consensus seems to have gradually emerged about the need to pursue low-key interactions with the Taliban to address security and humanitarian concerns. Gulf Cooperation Council countries should continue to coordinate their Afghan policy more closely and find a working formula to alleviate the hardship of Afghans.

OIC and IsDB have proved effective conduits to safely channel funds into Afghanistan, although their mitigation measures have fallen short of the mark. As long as these endeavors are geared toward the essential needs of the battered Afghan population and are solidly anchored on humanitarian grounds, the international community should not let Gulf partners alone shoulder the burden of providing the bulk of humanitarian relief to the country.

Leonardo Jacopo Maria Mazzucco is a researcher of the Strategic Studies Department at Trends Research & Advisory. He is also an analyst at Gulf State Analytics (GSA), a Washington-based geopolitical risk consultancy. Folow him on Twitter: @mazz_Leonardo.

Dr. Kristian P. Alexander is a senior fellow and the head of the Strategic Studies Department at Trends Research & Advisory, UAE.

Further reading

Fri, Sep 3, 2021

Afghanistan demonstrates why it’s time for a clear Syria policy, starting with northeast Syria

MENASource By Reem Salahi

If Afghanistan is to teach us anything, the Biden administration should not ignore Syria by having a non-existent policy. The longer the Syrian conflict continues, the more intractable and unmanageable it becomes.

Thu, Dec 15, 2022

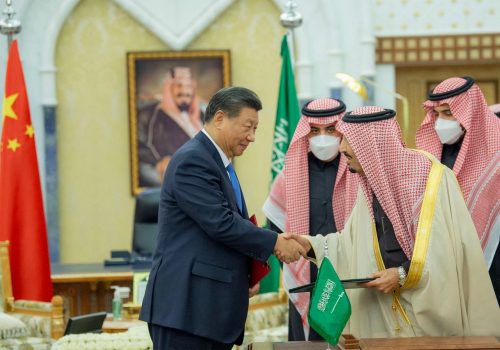

No, Xi’s visit to Riyadh wasn’t because of bad US-Saudi relations. It’s about much more.

MENASource By Jonathan Fulton

Given the bad state of US-Saudi relations, it is natural to see Xi’s visit in the context of geopolitical competition between Washington and Beijing, but that framework misses the bigger picture.

Thu, Mar 3, 2022

As Qatar becomes a non-NATO ally, greater responsibility conveys with the status

MENASource By R. Clarke Cooper

Although Qatar’s eligibility for MNNA status doesn’t automatically include a mutual defense pact with the United States, being designated a MNNA state is very much a declaration that the United States wants a deeper and stronger security-cooperation relationship with Qatar and expects the country to play a greater role in regional security.

Image: A high level delegation of the Taliban ruled Islamic Emirate led by Foreign Minister Maulvi Amir Khan Mottaki (center) left for Qatar on Friday Oct 8, 2021. Senior Taliban officials and U.S. representatives are to hold talks Saturday Oct 9 and Sunday Oct 10 about containing extremist groups in Afghanistan and easing the evacuation of foreign citizens and Afghans from the country, officials from both sides said. Its the first such meeting since U.S. forces withdrew from Afghanistan in late August, ending a 20-year military presence there, and the Talibans rise to power in the nation. The talks are to take place in Doha, the capital of the Persian Gulf state of Qatar. (Taliban handout via EYEPRESS)