What will minority and women’s rights look like in the new Syria?

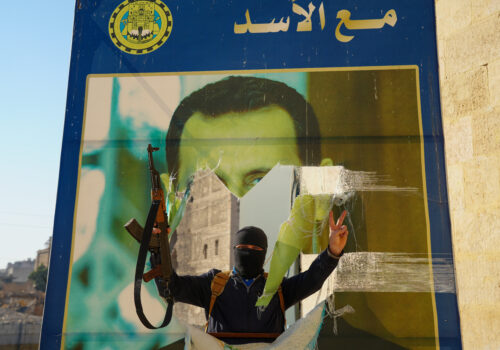

The fall of the Assad regime marked a seismic shift in Syria’s governance dynamics. The new administration, led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), is navigating a delicate balance between its ideological origins and the practical necessity of governance. One of the immediate challenges it faces is addressing the rights and concerns of Syria’s minorities and women. I witnessed this balancing act play out firsthand while in Damascus in the frenetic days following dictator Bashar al-Assad’s ouster. How the new transitional government responds to these challenges will be crucial for consolidating its internal legitimacy, managing societal cohesion, and engaging with the broader international community.

For minorities, between reassurance and skepticism

From the outset, the new authorities demonstrated a conscious effort to signal a departure from the divisive practices of their predecessors. In Aleppo, HTS contacted prominent Christian leaders and clergy across various denominations to repair strained relations and foster a sense of security. These meetings were not superficial; they included discussions on tangible grievances, such as the injustices faced by Christians in Jisr al-Shughur a year prior. Some of these grievances have since been addressed mainly through accountability and restoring properties to their rightful owners, an unprecedented move that underscores the leadership’s understanding of the need for inclusivity, albeit carefully managed.

Similar gestures were made towards the Druze community in Idlib Governate’s Jabal al-Summaq area, where HTS leadership engaged with representatives to rebuild trust and ensure that their communities were not targeted. Additionally, on December 17, leaders held dialogues with prominent figures from the Druze community in Suwayda and Jabal al-Arab, sending assurances of safety and future inclusion. For the Ismailis of Salamiyah, the transition of power was remarkably smooth, as the town surrendered without violence. This cooperative handover reflects longstanding tensions between the Ismaili community and the Assad regime, which had marginalized them over the years.

SIGN UP FOR THIS WEEK IN THE MIDEAST NEWSLETTER

However, the situation remains more nuanced with the Alawite community. The new government refrained from delivering targeted reassurances to the Alawites, instead embedding its messages of justice and reconciliation within broader declarations. The new authorities emphasized that no one would face retribution without due process and clear evidence of wrongdoing. The deployment of rebel forces in Latakia and its surrounding mountains occurred without notable violence, with explicit orders to safeguard public property and prevent retaliatory attacks. Such actions suggest an effort to mitigate fears of collective punishment among Alawites—a community burdened with its historical association with the Assad regime.

Still, there are lingering anxieties within minority communities. The Alawites, in particular, remain wary of the new leaders’ promises, balancing a cautious optimism with deep-seated concerns about potential reprisals. In response, some within the community have distanced themselves publicly from Assad, framing the current transition as an opportunity for a fresh start and a shared national future. Whether the new authorities can translate these gestures into meaningful inclusion will depend on their willingness to integrate minority representatives into future governance structures and decision-making processes.

For women, between pragmatism and policy gaps

The evolving role of women in Syria is shaped by societal necessity and practical realities. Syria’s protracted conflict has led to significant demographic shifts: countless men have been killed, displaced, or forced into exile due to military conscription, economic hardship, or combat involvement. As a result, women now bear much responsibility for sustaining households, working in various sectors, and managing day-to-day economic activities.

In urban centers and rural areas alike, women have maintained an active presence in the public sphere. Notably, no widespread attempts have been made to impose restrictive dress codes or curtail women’s mobility, in stark contrast to the fears many harbored when HTS first rose to prominence. Women freely participated in public celebrations across towns and villages, underscoring the relative ease with which they navigated public spaces under the new leadership.

However, women need to achieve meaningful political inclusion. While women are visible in mid-level administrative roles in the transitional government, there has yet to be any effort to appoint them to senior leadership positions or ministries. This mirrors a broader trend in conservative governance structures where women’s participation is often limited to symbolic roles. The new government’s failure to include women in decision-making risks alienating a critical population segment and undermining its claims of inclusivity.

Moving forward, the new leadership must recognize that empowering women is not merely a concession to international pressure but a practical necessity for rebuilding Syria. Women’s inclusion in governance, education, and economic development will be critical for addressing Syria’s demographic and financial challenges. The government can indicate its commitment to inclusivity with concrete steps, such as appointing women to leadership roles, supporting women-led initiatives, and ensuring equal access to education and employment.

Drafting a constitution

Despite the positive gestures made toward minorities and women, Syria’s new government under HTS leader Ahmed al-Shara faces structural and institutional challenges that threaten to undermine these early gains. Effective governance is not simply a matter of security or symbolic inclusivity; it requires building functioning institutions that deliver services, mediate disputes, and foster participation from all segments of society.

The need to integrate the experiences and expertise of Syria’s technocratic and bureaucratic workforce is at the heart of this challenge. The structure of Syria’s public administration going back decades included representation from various sects and backgrounds and significant contributions from women. Often overlooked in political narratives, this workforce remains vital to the country’s reconstruction and future success. The new government’s ability to retain and mobilize these experienced individuals within its evolving institutions will determine the effectiveness of its governance.

However, there are signs of tension between ideological considerations and practical governance. While Shara has shown a degree of pragmatism, particularly in dealing with local communities, the transitional government’s structures remain centralized and hierarchical, with power concentrated in a small leadership circle. This limits opportunities for inclusive decision-making and reinforces perceptions of exclusion among minorities and women.

To foster genuine participation, the new government must decentralize aspects of its governance, empower local councils, and integrate representatives from underrepresented groups. Decentralization has been a demand in many post-conflict contexts, allowing communities to manage their affairs while preserving national cohesion. In Syria, where local dynamics vary significantly across regions, such an approach would not only address the concerns of minorities and women but also strengthen the new authorities’ legitimacy.

The drafting of a new constitution presents both an opportunity and a challenge. On one hand, it offers a chance to codify the principles of inclusivity, justice, and representation essential for Syria’s long-term stability. On the other hand, the process is fraught with risks, particularly in a polarized environment where trust remains fragile. Minority communities and women must sit at the table during this process, ensuring their voices are heard and their rights are protected.

A constitution that explicitly guarantees the rights of minorities and women will strengthen the new government’s domestic legitimacy and address longstanding grievances that have fueled instability. It will provide a legal foundation for Syria’s governance, creating a framework that transcends political factions and ensures continuity in protecting vulnerable communities.

The test ahead

Syria is at a crossroads. The departure of the Assad regime has created a unique opportunity to redefine the relationship between the state and its people. The actions taken by Shara thus far—reaching out to minorities, refraining from imposing restrictive norms on women, and prioritizing internal legitimacy—reflect a pragmatic shift in HTS’s governance approach. However, these actions remain tentative and incomplete.

The true test lies in the new authorities’ ability to institutionalize these early gestures through concrete policies and legal frameworks. A new constitution that guarantees the rights of minorities and women will serve as a foundation for Syria’s future, ensuring that these rights are not contingent on political or ideological changes. Similarly, meaningful political inclusion—by appointing women and minority representatives to leadership roles—will signal a genuine commitment to shared governance.

For the Syrian people, the stakes are clear. After years of conflict and division, there is an opportunity to build a more inclusive and just future that reflects the resilience, diversity, and aspirations of all Syrians. The leaders of the new government face a critical choice: they can either embrace this opportunity and chart a path toward stability and legitimacy or retreat into exclusionary practices that risk perpetuating the very divisions they seek to overcome.

Sinan Hatahet is a nonresident senior fellow for the Syria Project at the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs and the vice president for investment and social impact at the Syrian Forum.

Further reading

Wed, Dec 18, 2024

The fall of the Assad regime is just the beginning of Syria’s quest for stability

MENASource By

Sectarian divisions and external actors threaten to render the fall of the Assad regime a new phase in Syria’s civil war rather than its conclusion.

Wed, Dec 18, 2024

Will Russia be able to keep its bases in Syria?

MENASource By Mark N. Katz

It would be in the United States’ and Israel’s interests not to give the new Syrian government reasons to let Russia keep those bases.

Thu, Dec 5, 2024

What does Turkey gain from the rebel offensive in Syria?

MENASource By Ömer Özkizilcik

The rebel offensive took many by surprise, but analysts familiar with the situation in Syria were aware that the rebels were prepared to launch it by mid-October.

Image: Religious leaders of Latakia address people as they celebrate after ousting of Syria's Bashar al-Assad, during a gathering after Friday prayers in Latakia, Syria, December 13, 2024. REUTERS/Umit Bektas