While the scale and volume of military interventions by China, Russia, and Iran are reportedly lower now than at the height of Cold War, the increasing risks of disruptive actions by these state actors and their proxies in a multipolar world require deterrence featuring robust technological solutions, which can only emerge from smart, adaptive policy.

The United States and its security partners are awaiting the Biden administration’s Global Posture Review, along with the potential expansion of security cooperation procedures, expanded congressional reviews, and a revision of the Conventional Arms Transfer (CAT) Policy—which would further protract an already lengthy arms-sale process. Meanwhile, dictatorial adversaries of democracy and freedom in Beijing, Moscow, and Tehran are aggressively seeking opportunities for disruption wherever Washington might expand or reduce security cooperation, or simply withdraw its presence. Ready access to low-cost, but effective, commercial technologies render that threat even more potent.

For the United States to remain a leader in this new multipolar world and more effectively plan its global posture, it must snap out of a Cold War-style mindset, cut down on bureaucracy, and refrain from expanding processes that hamstring security cooperation.

The Trump administration made some notable advances to promote innovation and protect US technological advantage through its 2017 National Security Strategy; 2020 National Strategy for Critical and Emerging Technologies, designed to actively promote innovation; and its commitment to revise the US export policy for Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS). These policies were a good start, but not enough. Now President Joe Biden has an opportunity to bring them to fruition.

To understand the rapid emergence of UAS threats, look no further than the growth of Iran’s military drone program in recent years, which also extends to Iran-backed groups across various regional conflicts. This includes Houthi rebels in Yemen using drones against Saudi Arabia, Hamas deploying them against Israel in the Gaza Strip, and Iraq-based Shia militia using them to attack US troops—likely including the recent drone attack on Al Tanf, a remote US outpost on the Syrian-Jordanian border. Iran’s increasing use of this technology, specifically “suicide” or “kamikaze” drones that fly into their targets and explode, requires integrated air defenses and Counter-Unmanned Aircraft Systems (C-UAS) technology. Regional US partners in the Middle East, which have increasing requirements to deter Iranian aggression, will seek every opportunity to acquire it from the US government.

The US security establishment has long acknowledged that adversaries like China and Iran are pursuing commercial, off-the-shelf technologies that can threaten US personnel, penetrate allies’ and partners’ air defenses, and generally challenge regional stability. But the US approach still has room for improvement.

As part of its new CAT policy, the Biden administration is considering expanding bureaucratic processes for arms sales to better safeguard US interests—but this inadvertently chips away at the prime placement of American aerospace and defense industries in the global marketplace. Extending the processes for military arms sales and transfers risks ceding the security cooperation space to US adversaries. The United States has a unique role in the world, and its national-security interests—including its defense industrial base—shouldn’t be compromised (certainly not by the government) in pursuit of a “level playing field,” as recently advocated by Assistant Secretary of State for Political-Military Affairs Jessica Lewis. For the US government to suggest putting US industry on par with competitors is counterintuitive; it is a national- and economic- security imperative for the government to bolster US industry to excel with every possible advantage.

US security cooperation historically encompasses facilitating arms sales, staging military training and exercises, developing interoperability among allies and partners, and bolstering the sovereign defense capabilities of security partners. All these efforts need to continue at a deliberate pace—but in a post-Cold War world, the United States no longer has a monopoly on arms sales with an overt technological advantage in all areas.

In recent years, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities became the focus of Chinese UAS production, and as then Chairman of the Joints Chiefs of Staff Joe Dunford noted in 2018, “Whoever has the competitive advantage in artificial intelligence and can field systems informed by artificial intelligence, could very well have an overall competitive advantage.” Many of us in the national-security enterprise at the time were also concerned with how AI innovation would shape the development of drones and integrated air-defense systems. With that technological competition heating up, allies and partners matter more than ever.

To remain the “partner of choice” for its allies and partners, the United States needs to work closer with them in collaborative partnerships, such as the trilateral AUKUS defense pact among the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom. It can also develop other proactive collaborative schemes in emerging technologies to enhance shared capabilities and interoperability, help security partners successfully meet updated UAS export policy, and aggressively advocate for and develop integrated air-defense capabilities.

For the sake of American interests, the US government must carefully foster its partnerships and spark a level of defense innovation to keep the United States and its partners truly secure.

R. Clarke Cooper is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, former assistant secretary at the US Department of State, a former senior intelligence officer for the US Joint Special Operations Command, and a combat veteran.

Further reading

Mon, Sep 27, 2021

The military, intel, and law enforcement must collaborate in this new counterterrorism era

New Atlanticist By R. Clarke Cooper

Addressing emerging threats means adopting an interagency and international approach to fighting them.

Fri, Nov 19, 2021

Climate security can help bring the US and France together once again

New Atlanticist By Marie Jourdain

After strained ties caused by AUKUS, how should the United States and France repair their bilateral relationship? By spearheading climate security.

Tue, Dec 21, 2021

The NATO-Russia standoff could redefine the transatlantic relationship

New Atlanticist By Andrew R. Marshall

The outcome of this dispute could rewrite the terms of security on the European continent for an entire generation.

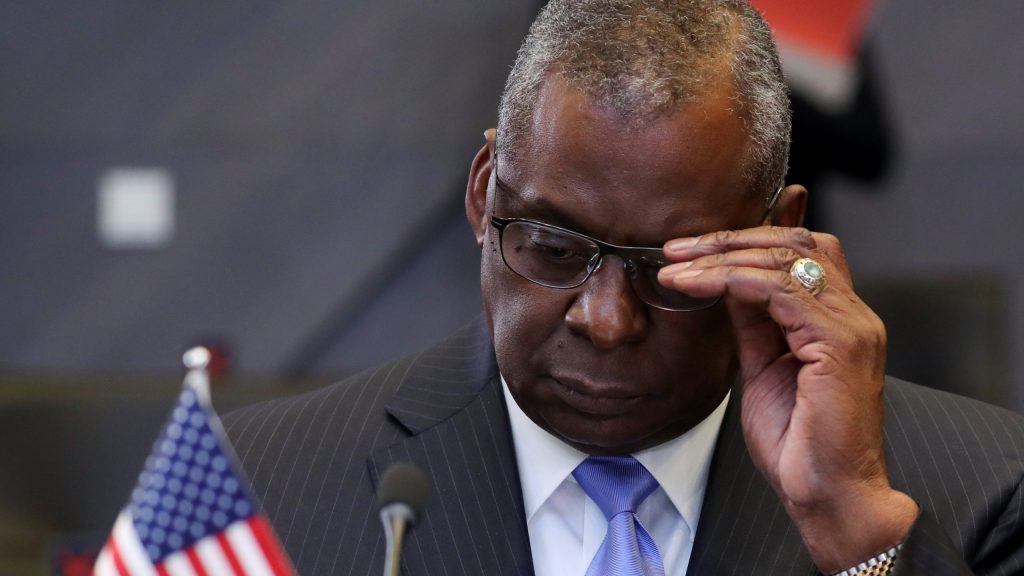

Image: US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin attends a NATO Defense Ministers meeting in Brussels on October 21, 2021. Photo by Pascal Rossignol/REUTERS