Watch the full event

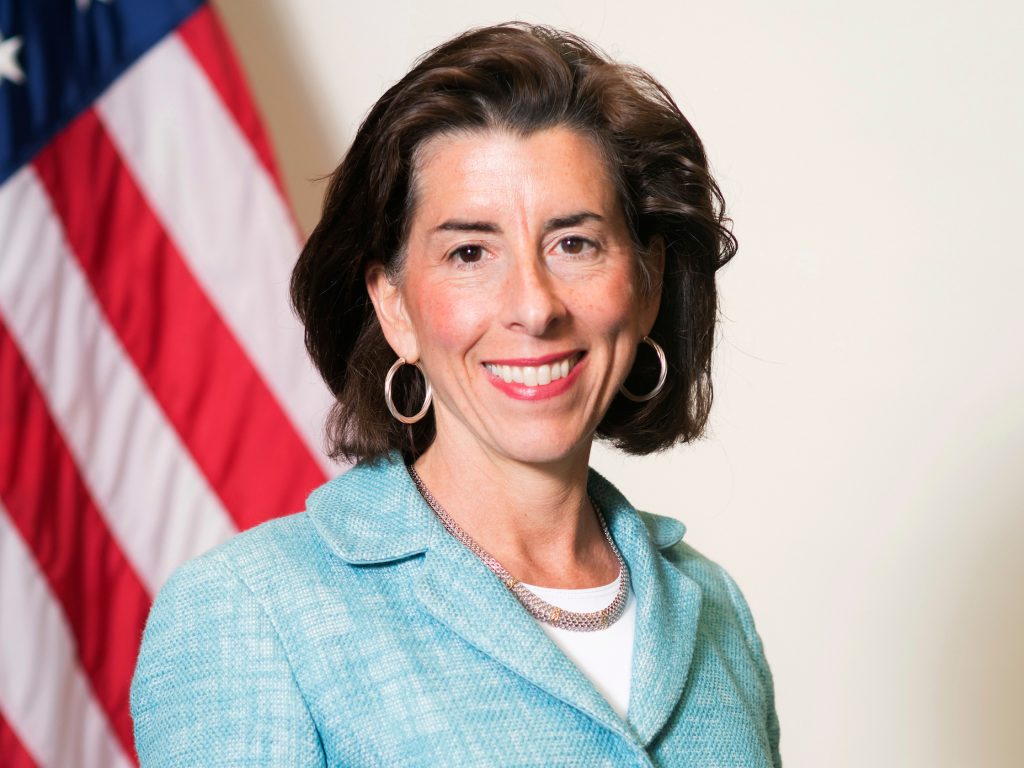

US companies are increasingly considering relocating their operations from China, said Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo, after many had to close their Russian operations earlier this year amid Moscow’s war against Ukraine.

“I’m hearing it from US CEOs, even from companies that have been manufacturing in China for decades,” Raimondo said Thursday in an Atlantic Council Front Page event. “The climate is getting tougher: uncertainty, [Chinese President Xi Jinping’s] increase toward autocracy. It’s hard to argue with them.”

Her comment came in a conversation with Keith Krach, co-chair of the Global Tech Security Commission—a joint initiative of the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub and the Krach Institute for Tech Diplomacy at Purdue University. It was one of many glimpses Raimondo offered into the high-stakes race between the United States and China to dominate tech and other sectors. Stability and security will increasingly be a linchpin of the American pitch to multinational companies.

“What I say to them is: ‘You want to go to places that are working with the United States to align their standards—tech standards, rule of law, transparency, anti-corruption,” Raimondo said, listing the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) as an example of an agreement that stands to benefit US companies interested in leaving China.

The United States is particularly interested in keeping China from building an edge in the advanced microchip technology sector, instituting chip export restrictions while considering further controls on Chinese semiconductor manufacturers. “The most cutting-edge technology in terms of chips has to be in America. It’s not now. It’s in Taiwan,” Raimondo said.

The commerce secretary will continue to play a major role in addressing that challenge as her department works to fortify US leadership in semiconductor research, development, and manufacturing, aided by fifty billion dollars in funding from the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022.

Here are some more highlights from the conversation.

Ambitious agenda

- Raimondo compared advancing chip technology to the Apollo program that succeeded in putting the first people on the moon. “We are soon going to be issuing a real call to the American people to step up. Which is to say, ‘Universities, we’re going to have produce orders of magnitude more engineers, more technicians, more computer scientists.’”

- The fifty billion dollars in CHIPS funding is just the start, Raimondo said, pointing to roughly two hundred billion dollars in total related funding across various US government agencies and plans to exponentially increase the value of that initial investment. “My job is to take that fifty billion and turn it into a couple hundred billion from all sorts of private capital. This has to unlock and crowd in other sources of capital.”

- A decade from now, Raimondo envisions the United States producing a million more engineers per year, 150,000 new manufacturing jobs, hundreds more chip-related startups, and, perhaps most critically, substantially decreasing its dependence on Taiwan for chips. “It’s just a new dawn for innovation,” she said.

Protecting American IP

- The positive effects of those investments will likely depend on whether the US can protect its advancements from foreign governments and companies. While some critics of the CHIPS Act argued there weren’t enough safeguards against intellectual property theft, Raimondo noted that Beijing didn’t seem to feel the same way: “I would say that to Congress, ‘You know how you know this bill is good? China’s lobbying against it.’”

- Raimondo warned that companies with a track record of trying to skirt or violate export controls wouldn’t stand to benefit from CHIPS Act funding. “If you take this money, you can’t be building leading-edge fabs [semiconductor fabrication plants] in China,” she said. “People would be shocked to know how much of the testing of the chips that goes into US military equipment happens in China… If you make the legacy chip in China, let it stay in China. We don’t want those chips coming into our military equipment, airplanes, cars, etc.”

- Creating a system of trust that protects companies with novel intellectual property is critical to the US strategy, Raimondo said. “If you look at the Global South and what China is doing in Africa, it’s insidious because when you change the standards to preference Huawei, or make it harder for a European or US technology provider, that bakes into the system a lack of trust.”

Beyond just chips

- Raimondo drove home the fact that eleven billion dollars of the CHIPS Act funding are dedicated to research and development. “Of all of this, that’s the piece I’m most excited about, because that’s the next generation,” she said. “That’s not building fabs today in the US, that’s: What’s the roadmap for future innovation?”

- That roadmap is important, Raimondo said, because it allows for the innovations to come in other tech sectors, including “AI, pharma, biotech, quantum, machine learning.” In those areas, the United States will need to work with European and Indo-Pacific trade partners to adopt shared standards, she added.

- Data privacy and “data used not for good” will become even more of a challenge, Raimondo said, noting that US soldiers today play video games made by Chinese companies on their phones. “That means China knows where every one of them is,” Raimondo said. “As we move further into what technology is capable of doing, trust becomes so much more important.”

Nick Fouriezos is an Atlanta-based writer with bylines from every US state and six continents. Follow him on Twitter @nick4iezos.

Watch the full event

Further reading

Thu, Sep 22, 2022

The dollar has some would-be rivals. Meet the challengers.

New Atlanticist By Ananya Kumar, Josh Lipsky

What are the realistic alternatives to the dollar that US and allied policymakers should be paying attention to? And how can they respond?

Tue, Aug 30, 2022

Deal or no deal, Chinese firms will still ditch Wall Street

New Atlanticist By Jeremy Mark

Despite a recent US-China agreement designed to end a decade-long auditing dispute, the era of Chinese firms' unfettered access to US equity markets is ending.

Thu, Aug 25, 2022

Delisting Chinese companies from the New York Stock Exchange: Signs of decoupling

Econographics By Hung Tran

China’s decision to delist five companies from the NYSE is motivated by its unwillingness to comply with US regulations.

Image: US Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo speaks about semiconductor chips subsidies during a press briefing at the White House in Washington, DC on September 6, 2022. Photo via REUTERS/Kevin Lamarque.