On Saturday, Germany’s center-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU) will elect a new leader to replace the retiring Angela Merkel. This means, with federal elections scheduled for September, that the party could be selecting the next German chancellor. The vote comes after Merkel’s chosen successor, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer (commonly known as AKK) resigned as party chair almost a year ago. She had been unable to control internal party divisions and master the coalition-building that has been so characteristic of Merkel during her eighteen years at the party’s helm.

Since then, the pandemic has repeatedly delayed the CDU’s selection of a new leader while drastically changing the domestic political outlook. Merkel’s management of the crisis has resulted in her approval ratings surging to new highs and helped her party recover from all-time lows in pre-pandemic polls. But whether any of the candidates can preserve, let alone expand, the new lease on life that Merkel’s resurgent popularity has lent the Christian Democrats in a Superwahljahr—a super election year of four state ballots and a federal election—is highly questionable.

Whatever the outcome on Saturday, it will likely mark the beginning of the end for the sober leadership style, centrist compromises, and coalition-building approach to governing country and party that so defined Merkel, Germany, and the CDU for much of her chancellorship. None of this should make even critics of her status-quo politics delight. And unlike the previous four German elections, when Merkel’s candidacy was a foregone conclusion, the 2021 CDU leadership contest might not determine Germany’s next chancellor.

Here’s a rundown of what to expect from the leadership vote, what to know about Merkel’s potential successors and the political dynamics behind the contest, and what all of this could mean for German politics.

Why the vote matters

Traditionally, the party chair of the CDU in an election year ends up being the candidate for chancellor for the party’s joint national list with its “sister party” in Bavaria, the Christian Social Union (CSU). But tradition might not hold in 2021.

After years of disagreements between the two sister parties over the 2015 refugee crisis —and despite a recent rapprochement—it seems like this setup won’t be automatic this time. A decision on the joint CDU/CSU Spitzenkandidat, or lead candidate, is expected sometime in March or April.

The leadership ballot is also a vote on Merkel’s centrist course, the electoral coalition she assembled as chancellor over the last 16 years, and the future positioning of the party in a transforming political landscape in Germany. For the first time in postwar German history, the CDU has a party challenger on its right flank in the populist, extremist Alternative for Germany (AfD). At the same time, from the left, the surging Greens are appealing to the centrist, female, and migrant vote that Merkel brought into the CDU tent.

With a conservative pitted against two moderates, the leadership vote thus also implies a strategic choice for the party post-Merkel. Should it return to its roots and sharpen its conservative profile to regain voters lost to the AfD on the right, which in turn would risk alienating the CDU’s broader electoral coalition of the last decade? Or should it double down on Merkel’s strategy of moving to the middle and write off its most conservative voters as a loss to its challenger on the right?

How the vote will work

On Saturday, the second day of the largely virtual party convention, 1,001 officials from local CDU chapters will vote digitally on three candidates. If no candidate secures an absolute majority in the first round, the two leading contenders will move to a second round. The virtual format will make situational swings, backroom deals, and leadership influence more difficult to predict than usual. We’ll know the winner at the end of the day. However, party bylaws require the virtual ballot to be confirmed by a subsequent mail-in vote, so the formal announcement will come on January 22.

Assessing the candidates

The field includes three official candidates and is notable for its lack of diversity: All three contenders are Catholic men who hail from Germany’s most populous state and the CDU’s largest state chapter, North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW).

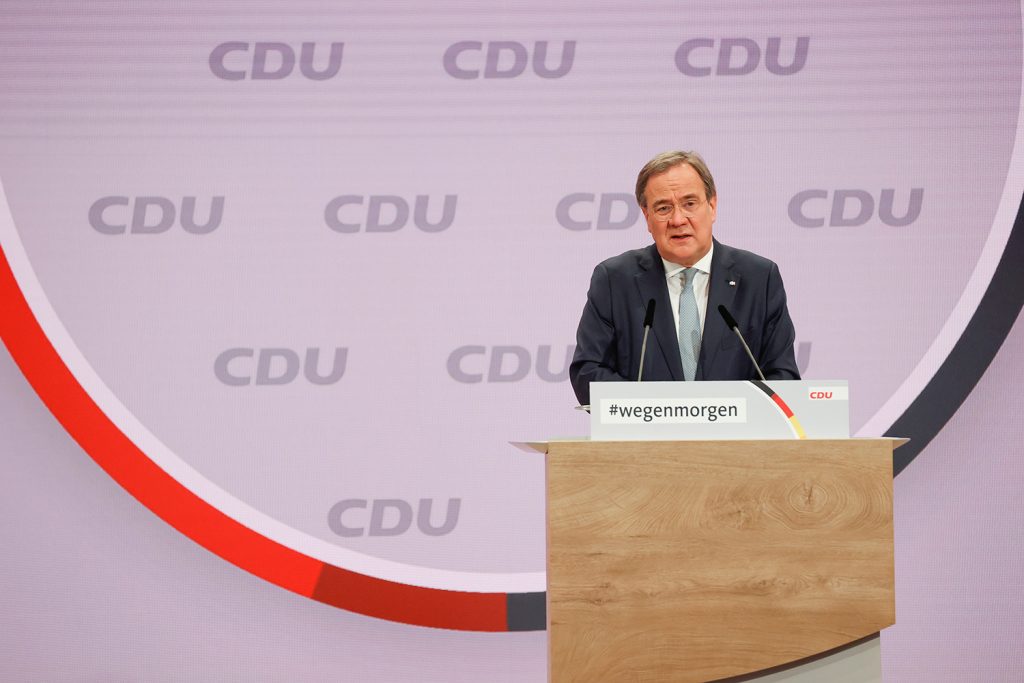

Armin Laschet: The continuity and consensus candidate

As prime minister of NRW, Laschet is the only candidate in a government office with executive powers. But he appears to have undermined his initial frontrunner status with weak crisis management during the pandemic. He has positioned himself as a champion of German business and export interests, evident in a reluctance to oppose China, Russia, and Nord Stream II, the controversial Russian gas pipeline. In an impressive move, he co-opted up-and-coming conservative hopeful Jens Spahn as his deputy candidate to shore up his support among traditionalists. The consensus option, Laschet is seen as a staunch Merkel ally in her moderate mold and a proponent of continuity in her centrist course. But he lacks the long-time chancellor’s political instincts and coalition-building genius.

- Pros: Laschet can leverage support from CDU leadership and the party’s largest state chapter in NRW, his executive experience, and his consensus appeal. His positions and style will make him a more compatible partner in a potential CDU-Greens coalition at the federal level.

- Cons: Conservative CDU rank-and-file oppose his pro-Merkel course of continuity. Few in the CDU and beyond see him as a strong nationwide candidate.

- What Brussels and DC might see: In the past, Laschet has expressed accommodating positions toward Russian President Vladimir Putin, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, and China, though it’s unclear how much these views would survive an ascendancy to CDU leadership or the German chancellorship. As a former member of the European Parliament, NRW governor, and native of the border town of Aachen, he knows the European Union (EU) well and thinks in European rather than more parochial terms—reflexes he has shown amid the pandemic by working closely with the neighboring Dutch and Belgian governments on cross-border travel and trade with his state.

Friedrich Merz: The pro-business, back to the future conservative

The economic liberal is the favorite of influential conservative and pro-business constituencies thanks to his promises to return the CDU to a more traditional posture. (He once argued that Germans should be able to figure out their tax returns on a beer coaster.) Outmaneuvered by Merkel in the early 2000s, he left politics for 15 years to work for a US hedge fund. Merz is often portrayed by his critics as an out-of-touch and gaffe-prone wealthy elitist unable to connect with the average voter’s concerns. His conservative views and values are often seen by moderates in his own party and the general public as out of step with the times. There are also doubts about whether he can handle a transformed German political and media landscape after such a long absence. Nevertheless, he has energized the CDU’s rank-and-file and its youth organization by promoting a more conservative profile for the party. He narrowly lost the 2018 leadership contest to AKK. There are also doubts about whether he can handle a transformed German political and media landscape after such a long absence.

- Pros: Merz’s plans to shift the CDU to a more conservative stance has the support of the party’s rank-and-file and youth movement as well as influential pro-business and conservative groups. He has some of the strongest appeal among conservative voters and could regain voters lost to the right-wing AfD.

- Cons: Merz’s conservative shift will concern the current CDU leadership. Such a shift would be detrimental to Merkel’s carefully constructed centrist national voter coalition, which has won her and the party successive elections. As a party leader and chancellor candidate, he would likely push mainstream voters to the Greens in the upcoming federal election and be a difficult partner in a CDU-Greens coalition. Few party officials may want to run the risk of having him trying to settle scores with an outgoing but popular Merkel in an election year.

- What Brussels and DC might see: Despite a short stint as a member of the European Parliament, Merz lacks a sophisticated understanding of today’s EU politics and has been a fiscal hawk on Eurozone policy. DC might take more favorably to his Wall Street connections, Atlanticist credentials, and willingness to tell Americans what they want to hear on foreign and defense policy, even if that might not mean committing to any real action on burden-sharing or defense spending.

Norbert Röttgen: The (relatively) progressive geopolitical strategist

The chairman of the Bundestag’s Foreign Affairs Committee, Röttgen has been the long shot-turned-dark horse in the CDU leadership race. He initially entered the contest at the behest of party seniors to keep the race open and competitive but has caught up through hard work, likeability, and his competitors’ poor performances. A relatively progressive intellectual seemingly without much of a base, Röttgen has impressed party members and outsiders with a modernizing approach. As a foreign-policy expert, he has assumed a higher profile thanks to recent debates in Germany over China, the poisoning of Russian dissident Alexei Navalny, and the potential ramifications of Nord Stream II. Röttgen beat Laschet for the NRW-CDU chairmanship in 2010. But he was then succeeded by Laschet as a result of Merkel’s intervention in 2012, following a poor state election performance by the Christian Democrats, which left a fractured relationship between Merkel and Röttgen.

- Pros: Röttgen’s moderate profile and foreign-policy views are highly compatible with a potential Green coalition partnership. His hard work and centrist campaign have surprised many, and he has moved up in the polls. Röttgen might come in second given that party officials get to decide the outcome—not the rank-and-file.

- Cons: Röttgen lacks a strong national profile and broad party base. Few see him as a candidate for chancellor, making a CSU contender for that national office more likely (see below). CDU delegates might not be willing to select Röttgen and give up their party’s claim to a federal candidate.

- What Brussels and DC might see: As a Russia and China hawk, a staunch critic of Nord Stream II, a professed Atlanticist, and a proponent of greater German responsibility in global affairs, Röttgen is what a Biden administration and European allies may want to see in future German leadership. But he has faced few tests under pressure in any of his official positions, and his lack of a party base for his views doesn’t bode well.

Are there any wild cards in the race?

There are persistent rumors that Jens Spahn, the young CDU hopeful and federal health minister, will make a leadership move and could emerge as a surprise candidate on Saturday. But Spahn is under increasing pressure for an allegedly disorganized government approach to the COVID-19 vaccine roll-out. For any leadership bid by Spahn to work, Laschet would have to decide to stay in NRW and let his deputy take the limelight, which seems unlikely at this stage.

Could the chancellor be from the CSU this time?

CSU Chairman and Bavarian state Prime Minister Markus Söder can build on increasingly strong polls at the federal level and his public-relations savvy to make a run at the chancellorship. Despite real questions about his state’s management of the COVID-19 crisis, he’s currently the person among all four candidates most trusted by Germans to hold the role of chancellor, by a wide margin. But Söder, something of a political shapeshifter throughout his career, is awaiting the results of the CDU election and its potential ramifications. Most recently, he has cozied up to Merkel and has even warned the CDU candidates of breaking with her centrist strategy, which is unusual coming from the traditionally more conservative CSU.

A Merz or Laschet victory on Saturday would likely rule out his candidacy, given the egos involved and Söder’s testy relations with both. But a combination of Röttgen as the CDU chairman and Söder as the CDU/CSU chancellor candidate could work well. In the end, however, Bavaria’s leader may choose to stay in Munich and avoid the uncertainty of running for the highest federal office in Berlin—something only two of his CSU predecessors dared to do in postwar history, with both ultimately failing.

What do the polls say?

Most polls of the CDU’s base have Merz ahead of Röttgen, followed by Laschet in third place. None of the three candidates, however, is outperforming Söder in popularity among CDU supporters and the general public. On the flip side, the delegate format at the virtual convention means that polls among CDU members or the general electorate are a poor indicator of how Saturday’s vote will go. During the vote on Saturday, strategic considerations—from general electability and party posture vis-à-vis the Greens, the CSU, and/or the AfD, to compatibility with potential coalition partners—may guide the decisions of mid-level party officials more than the views of the rank-and-file.

Whatever the outcome on Saturday, the search for Merkel’s successor is unlikely to be over. None of the candidates, including Markus Söder, is expected to be able to fill her shoes. But the choice of CDU leader will at least give an initial indication of what strategy the party will pursue in a major election year for Europe’s largest political and economic power—whether it will embrace a new conservatism or a continuation of Merkel’s centrism.

Further reading

Image: The new elected Christian Democratic Union (CDU) party leader Armin Laschet gives a speech during the second day of the party's 33rd congress held online amidst the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, in Berlin, Germany January 16, 2021. Odd Andersen/Pool via REUTERS