Central Asian leaders are walking into a potential trap, guided by a recent rush of Chinese persuasion and engagement to align with the eastern power. A region that even within the last few years championed a form of non-alignment among large powers—a balancing act Kazakhstan termed “multi-vector diplomacy”—today risks becoming increasingly dependent on, and therein possibly beholden to, Beijing.

Five Central Asian leaders—from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan—just visited Xi’an in central China to meet Chinese leader Xi Jinping for the C+C5. The new China-led summit is aimed at elevating regional ties with Beijing, and it is the first of three events this year that brings Central Asian leaders face to face with Xi. At the summit, the Chinese leader took steps to persuade the Central Asian countries that, in this polarizing world, they can count on China and they are at one with the Chinese “common destiny.”

There were inducements to help with this persuasion. Kazakhstan and China signed a deal for a new industrial transfer program, and Beijing pledged to support Kazakh businesses operating in China and to increase the number of tourists visiting the country. Kyrgyzstan and China have announced a new investment fund, extended an invitation for China to open branches of its banks in the country, and added Kyrgyzstan to China’s list of countries Chinese nationals are allowed to visit as tourists. Looking at the bilateral statements coming out of the Xi’an Summit, the China-Uzbekistan statement has twenty-eight items, the China-Kazakhstan statement seven, China-Kyrgyzstan eleven, and China-Tajikistan eighteen. Most importantly, China is planning to open a C+C5 secretariat with nineteen separate channels of direct engagement with the region, moving away from its long preference of working bilaterally to instead attempt to tie the whole of Central Asia’s outlook to China no matter what domestic political changes occur there.

Central Asian countries vary in their receptiveness to China’s overtures. For example, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have previously shown greater reluctance to engage with Beijing than some of their neighbors. But there is a clear region-wide trend of closer alignment with the large power to the east.

At the same time China is ramping up its persuasion campaign, the opportunities for Central Asian countries to cooperate with foreign actors other than Beijing have shrunk. Russia is embroiled in its war with Ukraine. The United States’ exit from Afghanistan reduced attention to the wider region from Washington. Moreover, recent programs intended to increase cooperation with Central Asia led by Turkey, India, the European Union, and the United States are not matching up to growing Chinese initiatives across all sectors working to forge deep regional dependence on China.

There’s more. China is exporting its governance style—which easily accommodates authoritarian practices—to Central Asia. By oppressing civil society, detaining or expelling journalists, and arresting leaders of protests ahead of and after demonstrations, Central Asian governments have shown their preference for a governance style based on the one that they perceive as successful in China.

China has also made economic-integration efforts that feed the local rent-seeking appetite, discouraging region-wide commitments to reforms and to developmental aid from the international community that is conditioned on reforms. In Kyrgyzstan alone, between 2014 and 2019, there were five major corruption scandals involving a Chinese company and elite-level local politicians, including two former prime ministers and two former mayors of large cities.

China actively works to sustain its dominance in commodity trade with Central Asia via its state-subsidized railway which has, in the past decade, discouraged Central Asia from investing in a new trade route—the Middle Corridor, which connects the region to Europe via the Caspian Sea—therein disincentivizing trade with Europe.

While some European countries have been willing to transfer industrial technology to the region, China has been more active in such cooperation in recent years. There are fifty-six active Chinese industrial transfer programs for Kazakhstan, perhaps a dozen projects in Uzbekistan, forty in discussion with Kyrgyzstan, and several in Tajikistan. These include the recent setting up of a nuclear-rod production line in Kazakhstan, which contains the world’s second largest uranium reserves.

In the area of education, China is offering a number and variety of programs to the region, directly competing with other foreign actors for the brightest Central Asian students. It is also experimenting with new vocational initiatives such as the Luban Workshop, China’s skill-training project, in the hopes of deepening trade ties. Its first in Central Asia opened in November in Dushanbe, Tajikistan.

Putting the multi in multi-vector

Despite Central Asia’s desire to prevent any great power from becoming dominant in the region, the “multi-vector” approach has proven difficult to implement in practice as Chinese ambitions and activities have rapidly increased in the region. Internally, Central Asian leaders explain their catering to Chinese interests as a matter of being constrained, that they are landlocked and share a long border with China. Central Asian experts often argue that the region has no choice but to maintain close relations with its giant neighbor.

This rationale amounts to an unnecessary narrowing of possibilities. Compare it to Mongolia, whose prime minister says that, despite dependence on China for trade and Russia for fuel, the country’s policies are not so deeply influenced by Beijing or Moscow. “[Our] people’s mindset and society is very different from those countries,” Prime Minister Luvsannamsrai Oyun-Erdene said earlier this year. Serious commitments to democratic governance since the 1990s and continuous political will have paid off over the years, creating in Mongolia a vibrant civil society and a shift of political identity from Central Asian to Northeast Asian, aligning more with South Korea and Japan. In this way, Mongolia empowers itself to maintain a more independent foreign policy.

What might drive Central Asia to look beyond China? Drastic social changes are one possibility. In fact, Russia’s ongoing aggression toward Ukraine is driving active discussions in Central Asia about decolonization, a topic that would have been considered taboo just one generation ago. Many in Central Asia now recognize that prolonged continuation of Russian influence has had serious consequences to political and social life, and they have turned to revive previously repressed Central Asian languages and national heroes as a step toward more autonomy.

As the region further detaches from its history under Soviet imperialism, Central Asian countries will likely undertake an even greater search for national identity. China, foreseeing such a search beginning, has paid serious efforts to promoting select stories that depict “harmonious Silk Roads.” However, this is a strange concept to impose on Central Asians as many grew up learning that the Great Wall of China was built after continual attacks from Turkic tribes. China’s abuses toward the Turkic population in Xinjiang, most notably the Uyghurs, have not yet stopped Central Asian elites from supporting Beijing internationally; however, Turkey and other actors have in comparison much better appeal and authenticity when it comes to historical ties, language, and cultural affinity with the region. Led by Turkey, the Organization of Turkic States could grow into another serious vector for Central Asia moving forward to rebuild its Turkic identity, develop stronger relations in the region, and be empowered to implement a foreign policy and development pathway less in the shadow of China or Russia.

Given time, Central Asians may find their historical roots and culture inseparable from their Turkic counterparts in Xinjiang. It could become clearer to Central Asian countries that their own historical experiences with the Russian Empire are no different than the experience of those in Xinjiang under Chinese rule. Acknowledging this would also encourage Central Asian countries to look for connections beyond Beijing.

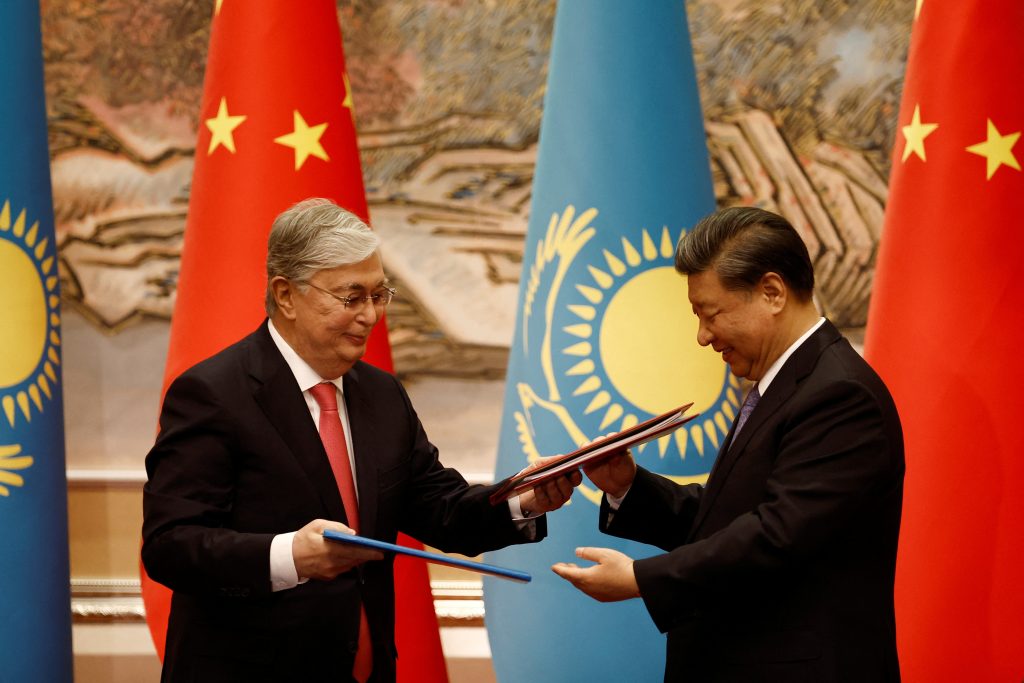

The photos of leaders shaking hands in Xi’an may bolster the impression that China has secured Central Asian loyalty. If so, it might only be for the short term. Sooner or later, the landlocked region will likely step back from an overly China-driven diplomacy. When that happens, Central Asian countries could focus more on cultivating and balancing multiple options abroad and on developing their regional identity, foreign-policy strategy, trade independence, and security.

Niva Yau is a nonresident fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub. Her research work focuses on China-Central Asia relations and China’s new overseas security management infrastructure and initiatives. She is based in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan.

Further reading

Sat, May 20, 2023

The US can help Central Asia avoid China’s awkward embrace

New Atlanticist By John E. Herbst, Andrew D’Anieri

China just wrapped up a summit with Central Asian countries, but the US should not cede the territory. Washington should energize economic and security cooperation.

Fri, Oct 7, 2022

What Xi Jinping’s third term means for the world

Issue Brief By Michael Schuman

It has been widely believed for some time, both inside and outside of China, that current Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping will break with modern precedent and extend his reign into a third, five-year term. Xi, who also serves as the country’s president, has been working toward this outcome for years.

Thu, Mar 30, 2023

Experts react: Your guide to the Taiwanese president’s trip to the US and Central America

New Atlanticist By

President Tsai Ing-wen's trip comes as US tensions with China are nearing a boiling point, and Taiwan is hustling to hang on to its allies in Latin America.

Image: Chinese President Xi Jinping and Kazakhstan's President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev exchange documents during a signing ceremony, ahead of the China-Central Asia Summit in Xian, Shaanxi province, China May 17, 2023.