When Russia invaded Ukraine, Germany painfully realized that its business-oriented approach to geopolitics and Moscow had failed. Decades-long criticism of Germany’s energy ties with Russia, and its failure to meet the 2 percent gross domestic product (GDP) defense target for NATO members, had come to a head. Against this backdrop, Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s Zeitenwende speech to the German Bundestag on February 27, 2022—three days after the invasion—was a political Produnova: an inherent admission of failure, countered by a forward somersault on policy. He announced a one hundred billion euro special defense fund and vowed to exceed NATO’s annual spending goal, send arms exports to Ukraine, and reduce energy imports from Russia.

A year ago, commenting on this policy shift, I wondered: “When the dust settles, and the adrenaline and euphoria dissipate… Will this change last?”

Undoubtedly, Germany has come a long way. It has cut its Russian natural gas imports, is a significant contributor of military aid to Ukraine, has approved the purchase of F-35 fighter jets from the United States, and is now sending Leopard tanks to Ukraine. However, these have arguably been tactical responses to political pressure and situational developments. Doubts remain about whether the Zeitenwende is a structural and mentality change in foreign and security policy.

Even if the spirit is willing, the flesh is weak. That is hampering the implementation of key Zeitenwende elements.

First, Germany’s bureaucratic procurement processes are likely to wear the special defense fund down. Meanwhile, inflation has eaten into it—one hundred billion euros already has been reduced to roughly eighty-seven billion.

Second, Germany remains unlikely to meet the 2 percent NATO spending target. It is expected to come in just below 2 percent until 2027, after which defense spending is expected to fall back to around 1.2 percent of GDP. In order to really modernize its military, Berlin needs a long-term fix. Yet unlike Japan, which intends to increase defense spending via taxation, Germany has no structural solution for a permanent increase of the defense budget. Without this, the special defense fund would be nothing more than a flash in the pan.

This conundrum is taking place in the context of an increasing budgetary struggle within Germany’s government coalition. Greens and the liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP) have already locked horns over the 2024 budget. This fight between Economy Minister Robert Habeck (Greens) and Finance Minister Christian Lindner (FDP) has come out into the open, with the former calling for an increase in tax revenues and the latter ruling out tax increases and intending to stick to Germany’s constitutional debt brake (which limits budgetary room for maneuver to increase defense spending). This struggle is very likely to increase over the coming years, as different demands—ranging from social support measures and Germany’s green energy transformation to the need to increase defense spending—will be placed on the budget.

Third, if the Zeitenwende is a structural and mentality change in German foreign and security policy, then it should be about more than just getting the military back in shape. It must include structural proposals for strengthening Germany’s intelligence services, cyber capabilities, and resilience to hybrid threats. However, there has been little focus on these aspects so far.

There is great hope that Germany’s national security strategy will address these questions. But so far, the strategy has been delayed due to political fighting between parties of the ruling coalition. Structural proposals, such as the establishment of a US-style national security council, have been scrapped.

Lastly, the real test of Germany’s Zeitenwende will be China. Here too, there are disagreements within the German government coalition and business community. One leading figure of the chancellor’s Social Democratic Party has argued that “just because the ‘change through trade’ policy failed with [Vladimir] Putin doesn’t mean it has to fail with Beijing,” while a number of German corporations are doubling down on their presence in China. For some, old habits die hard.

In spite of this, there is an overall understanding in the German government that it is not wise to be economically dependent on China. “Diversification” has become the narrative with regard to Beijing. However, what about deterrence?

Diversification is a defensive and trade-oriented policy. It aims to reduce economic risks from China, while enhancing economic opportunities in the rest of Asia. It comes across as a salesperson’s approach to geopolitics, an evolution of—rather than a break with—Germany’s “change through trade” mentality.

De-risking economic ties with China is important, and so is greater political and security engagement in Asia. As highlighted by Liana Fix and Thorsten Benner in Foreign Affairs: “Instead of ‘change through trade,’ Germany—in conjunction with other Western partners—will need to employ a ‘peace through strength’ approach to dealing with Russia and China.” Increased political visits to Asian partners and recent arms exports to Singapore and India have been successful steps in this direction.

Yogi Berra once quipped: “In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. But in practice there is.” It’s been a year since Scholz announced the Zeitenwende. In that year, a lot has happened. At the same time, there have been areas where little progress has been made. The Zeitenwende remains under construction.

Roderick Kefferpütz is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center and a senior analyst at the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS).

Further reading

Thu, Feb 23, 2023

Zeiten-when? Scholz needs to stop standing in the way of Germany’s foreign-policy turning point.

New Atlanticist By

The Zeitenwende is the chancellor’s brainchild, yet he has been its major roadblock. Scholz has habitually hesitated when faced with key decisions.

Thu, Feb 2, 2023

In 2022, the war in Ukraine awakened Europe. Here’s how it must adapt in 2023.

New Atlanticist By

How will the EU continue to bolster its security? Can Brussels forge a new path toward better relations with its partners? Our experts give their recommendations on how to get there.

Fri, Jan 20, 2023

Like it or not, Europe can only tackle its big challenges with Franco-German consensus

New Atlanticist By Marie Jourdain, Jörn Fleck

The January 22 France-Germany summit, amid bumpy relations between the two powers, comes at a pivotal time for Europe and the transatlantic alliance.

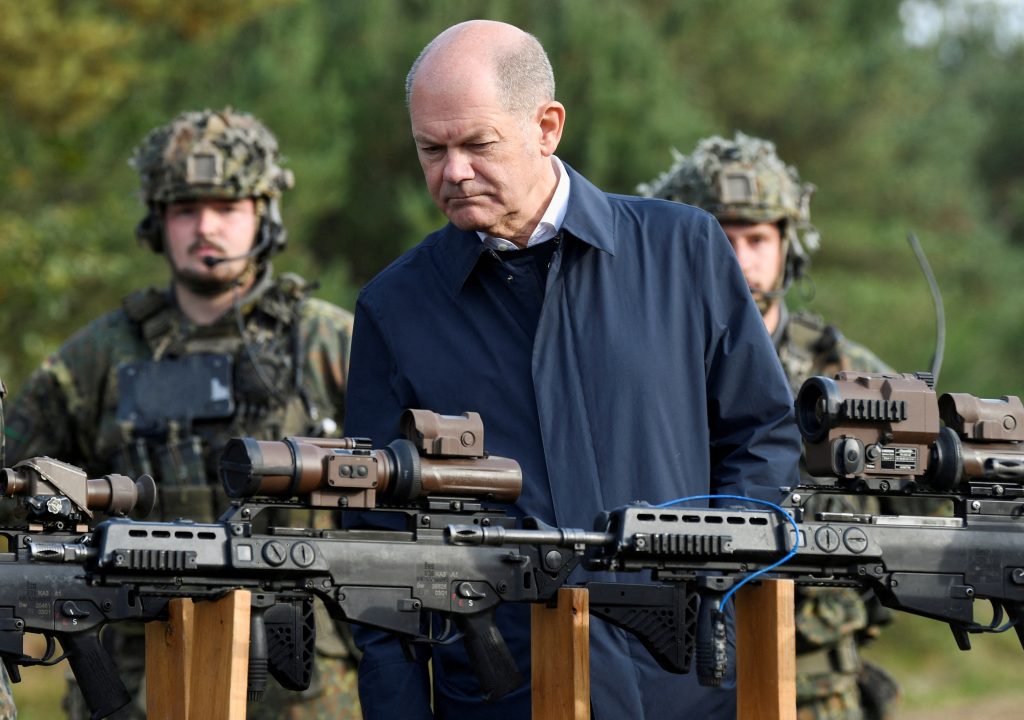

Image: German Chancellor Olaf Scholz looks at weapons during a visit to a military base of the German army Bundeswehr in Bergen, Germany, October 17, 2022. REUTERS/Fabian Bimmer TPX IMAGES OF THE DAY