The administration of US President Joe Biden has been intent on strengthening its diplomatic position in Asia to counter China’s growing influence. In May, Biden held meetings with leaders from Japan, India, and Australia, during which they discussed an array of China-related geoeconomic issues. In August, Biden hosted the Japanese and South Korean leaders at Camp David to discuss how these countries can bolster their security in Asia. Biden next plans to visit Vietnam on September 10. Other members of the administration have visited the region often this year, too. Just this week, Vice President Kamala Harris traveled to Indonesia for a meeting of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or ASEAN.

These visits build on last year’s US diplomatic initiatives in Asia. In 2022, the Biden administration launched the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity with twelve partners. The initiative seeks to “help lower costs by making [US] supply chains more resilient in the long term.” In addition, the administration announced the ASEAN Comprehensive Strategic Partnership that seeks to establish “deeper bonds with Southeast Asian partners” that the United States will aim to “expand regional diplomatic, development, and economic engagement” in the region.

These successes suggest that the Biden administration is serious about the United States’ role in Asia. But it has too often overlooked China’s bid for a sphere of influence in Central Asia. As the upcoming US-Central Asian summit on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly approaches, the administration should reenergize its engagement with the region, not just because of Beijing’s ambitions there, but also because doing so supports core US interests.

Central Asia’s importance

Sandwiched between Iran, Afghanistan, China, and Russia, the five Central Asian republics—Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan—have a combined population of more than 78 million people, possess a treasure trove of natural resources, and occupy a strategic position at the heart of Eurasia. Central Asian countries manage most of the international fallout from the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan, have absorbed Russians fleeing conscription, and remain an unappreciated link in the international security architecture. An increased Chinese presence in Central Asia would present the People’s Republic of China (PRC) with additional geoeconomic leverage against the West, and it would grant Beijing greater freedom of action in its international designs. Moreover, the PRC could consolidate its already hegemonic monopoly over rare earth elements mining and processing—vital for emerging green technologies—by cutting off an emerging alternative supplier of rare earth elements to the West.

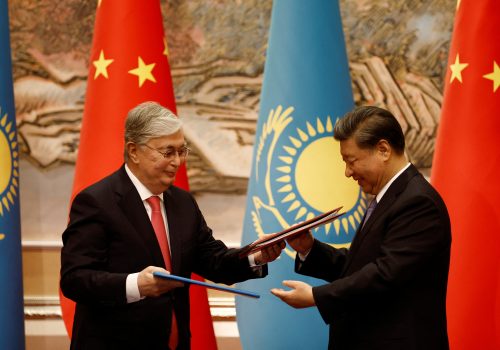

These states have long sought Western influence to stymie their problematic neighbors and solve local issues. Kazakhstan’s founding president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, for example, worked with the United States in the 1990s to dismantle the world’s fourth-largest nuclear arsenal and protect nuclear material from terrorists. Since then, the US-Kazakh relationship has continued. In February of this year, the current president of Kazakhstan, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, praised the US-Kazakh relationship, stating that Kazakhstan appreciates the “continuous and firm support of the United States for [its] independence, territorial integrity, and sovereignty.”

Even more recently, Uzbek Ambassador to the United States Furqat Sidiqov stated that the United States is an important partner, with “long-standing friendship and cooperation.” Turkmen Ambassador to the United States Meret Orazov, too, has voiced appreciation for US consultations with with Central Asian states.

Even though the Biden administration recognizes the region’s geopolitical and geoeconomic potential, action has been lacking. To date, no US president has visited the region, and there are no planned presidential visits in the future. At the same time, Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin lavish attention on the region, creating an easily remedied missed opportunity. A summit in May between Xi and the five Central Asian leaders boosted Chinese investment in the region. Beijing is currently the biggest consumer of Central Asian gas. As Russian influence recedes due to Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine, China, not the United States, is filling the gap.

US actions, by contrast, appear to neglect Central Asia’s strategic location and potential. Since independence, Kazakhstan (the lead diplomatic actor in Central Asia) has followed Nazarbayev’s multi-vector foreign policy doctrine. This doctrine, which advocates cooperation with the West to balance out its neighbors and promote reform, has provided numerous opportunities to the United States and its allies that they are reticent to exploit, such as greater cooperation in the energy sector.

What the United States should do

The United States has taken some actions to increase diplomacy, but not enough. Beginning in 2015, the C5+1 Diplomatic Platform, which includes the five Central Asian republics and the United States, is a good start at enhancing mutual cooperation. The United States and Central Asian countries have formed economic, energy, environmental, and security working groups to help strengthen Central Asia’s position vis-à-vis Russia and China, but these groups often lack direct US cabinet-level involvement, independent decision-making capacity, and adequate funding. It appears, however, that the administration is beginning to place a greater emphasis on this group, as it recently announced the US-Central Asian summit for later this month.

In February, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken visited Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. During the trip, Blinken said that the United States would help these countries “develop the strongest possible capacities for their own security, their growing economic prosperity, and the strength and resilience of their societies.” Blinken spoke wisely, but US action must now follow this rhetoric. For more than thirty years, the United States has been strategically underinvested in a region that is not demanding handouts but basic normalized relations, including permanent normal trade relations. Many of these countries, specifically Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan, cannot normally trade with the United States, despite their adherence to International Monetary Fund and World Trade Organization regulations, because of an archaic law directed at the Soviet Union, the Jackson-Vanik amendment. Originally conceived to protect Soviet Jewish emigres, it became an impediment to US policy when the amendment morphed into a catchall policy for any democratic deficit, while failing to recognize considerable local progress and human rights advances.

Congress repealing the Jackson-Vanik amendment would enable the United States to boost Central Asia’s economy and markets while furthering the US foreign policy objective of countering Chinese influence in the region. Currently, Central Asia relies heavily on Russia to export goods and commodities, including oil. According to a World Bank report released in March, Central Asia has significant natural resources and the human capital to enable mutually beneficial trade.

To counter past mistakes and support stronger ties, the United States should encourage the economic integration of the five Central Asian states and the development of infrastructure on the Caspian Sea. This would enable the Central Asian states to cooperate with the states of the Caucasus to more fully develop the Middle Corridor, a route from Central Asia to the outside world via the Caspian and Caucasus that would enrich the region while bypassing Russia. This has been on Central Asian countries’ agenda since the collapse of the Soviet Union and was one of the goals of Nazarbayev’s multi-vector foreign policy. Helping local actors with this would create a long-term economic basis to balance Chinese and Russian influence in the region.

Lastly, the United States could expand on its work with Central Asia to promote security in the region. Local efforts for nuclear disarmament are already well advanced. When the Soviet Union collapsed, Nazarbayev led the effort to declare the Central Asian Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Treaty. The legally binding treaty states that the five countries will “not manufacture, acquire, test, or possess nuclear weapons.” Authorities from the Central Asian states are cooperating with US officials to prevent nuclear materials from ending up in the hands of non-state actors. This has even led Kazakhstan to cooperate with the International Atomic Energy Agency and countries aspiring for peaceful civilian nuclear power to create a low-enriched uranium bank in 2019. Aside from this nuclear nonproliferation collaboration, the United States has also invited the five Central Asian countries to participate in the State Partnership Program. The program, which was established by the US Department of Defense and Department of State in 1993, seeks to “assist the former Warsaw Pact and Soviet states in their democracy efforts and reform their defense forces.” In the case of Central Asia, the United States is partnering its “military forces through regular exchanges focused on humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, crisis management, border security, [and] officer development.” To date, several US National Guard units are engaged with the military forces from the five Central Asian states. The United States can build on these existing partnerships to enhance security cooperation in the region.

The United States has been repeatedly presented with golden opportunities to more substantially engage with the Central Asian republics, which it has thus far failed to capitalize on. If the United States continues to let opportunities slip by, then it should expect more headlines about Chinese successes in the region. The upcoming C5+1 summit in September provides another such golden opportunity for deeper engagement with Central Asia that the Biden administration should seize while it has the chance.

Mark Temnycky is an accredited freelance journalist covering Eurasian affairs and a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center. He posts on X at @MTemnycky.

Further reading

Mon, Aug 14, 2023

The United States can’t offset its rivals in Central Asia alone. Turkey can help.

TURKEYSource By

Turkey is well-positioned to counter US rivals in Central Asia by expanding its influence and diversifying the region's partners.

Sat, May 20, 2023

How dependent is too dependent on China? Central Asia may soon find out.

New Atlanticist By Niva Yau

A region that even within the last few years championed “multi-vector diplomacy” today risks becoming dangerously dependent on Beijing.

Tue, Mar 28, 2023

Russia’s Ukraine invasion is eroding Kremlin influence in Kazakhstan

UkraineAlert By

The invasion of Ukraine was meant to advance Vladimir Putin’s vision of a revived Russian Empire. Instead, it is forcing other neighboring countries like Kazakhstan to urgently reassess their own relationships with Moscow.

Image: US Secretary of State Antony Blinken shakes hands with Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev during a meeting in Astana, Kazakhstan, February 28, 2023. Olivier Douliery/Pool via REUTERS