On July 29, 2021, the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center hosted the second launch of its report, reimagining the US-India trade relationship, curated by South Asia Center non-resident senior fellows Ridhika Batra, Mark Linscott, Harsha Vardhana Singh, and non-resident fellow Anand Raghuraman. The panelists included Suhail Nathani, managing partner at Economic Laws Practice; Shamika Ravi, director of research at Brookings Institution India Center; and Soumaya Keynes, Europe economics editor at The Economist. Non-resident senior fellow Ridhika Batra moderated the discussion, and introductory remarks were made by Irfan Nooruddin, director of the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

This conversation aims to identify Indian perspectives in understanding the US-India bilateral trade relationship, and is a part of the South Asia Center’s US-India Trade Initiative.

The US-India trade relationship through an Indian Lens

The discussion began with an introduction to the current state of the bilateral trade relationship and how Indian institutions differ from those in the US. As mentioned in the report, Shamika Ravi highlighted the role of “institutional biases” and “historical baggage,” in creating hurdles for trade, including a declining trade to GDP ratio and India’s continued struggles with trade negotiations. She attributed this to a lack of technical details and empirical evidence available in the domestic context, which has allowed for a sense of fear and uncertainty to grow. Likewise, Dr Ravi also points to the complexity of the Indian economy, where individual states play a significant role in negotiations. Mr Suhail Nathani further added to this point, highlighting the role of political changes in both countries that continuously affect the trade dynamic. Mr Nathani also expanded on India’s structural and historical realities, which have made trade agreements difficult. In particular, he highlighted how historically, trade has been limited to its use as a tool for diplomacy. Similarly, it has also been limited to traditional industries due to protectionist policies in India. Furthermore, the relationship has also faced significant barriers surrounding issues such as digital trade and data localization.

Despite being the largest global democracies, and aligned on various matters, the US-India trade relationship faces significant obstacles. The question remains- how can these two countries build a stronger, more fruitful relationship on the trade front? Evident from the discussion, great potential does exist. In particular, Dr Ravi stresses the importance of increasing empirical knowledge and research to expand the relationship and reduce the uncertainty surrounding trade. Likewise, as mentioned in the report, Dr Ravi also stressed the notion present in the report that “India is not a priority for the US,” thus, both panelists agreed that incrementalism or slowly building the relationship is a steadfast approach. Likewise, Mr Nathani also highlights the various area opportunities for trade negotiations, which extend to climate change, technology, and healthcare, particularly evident during the pandemic.

China and Beyond: Assessing the role of geopolitics in the US-India Trade Relationship.

Geopolitics is crucial to understanding how the US and India engage in trade. China’s rising role in the region, and the formation of the QUAD, have created new avenues for engagement. Ms Soumaya Keynes highlighted this reality, asking the panelists to expand on how the US and China’s “geopolitical rivalry” influences the US-India trade relationship. Dr Ravi identified China as the “converging point” in the relationship, bringing India and the US’s strategic interests in alignment with its trade interests. Likewise, according to Dr Ravi, China’s role in the region has influenced India’s policies greatly, from supply chain disruption to border issues. Mr Nathani also highlighted how the local telecommunication industry has seen an immense shift in response to this “geopolitical reality.” The audience also partook in the discussion, inquiring, “had there been no emergence of China as a threat to the US supremacy and global word order, would the US still be interested?” Mr Nathani emphasized the India centric perspective stating that while China does play a role in the US’s policy toward India, India is still one of the largest markets in the world, and the two nations have many fronts to negotiate on, including trade and even carbon pollution, harboring what he described as a “natural” connection.

Later in the discussion, the panelists moved beyond China, looking at how broader geopolitical opportunities have arisen in the past few years, with an emphasis on the QUAD. Ms Batra asked the panelists what possible benefits could come from trade discussed by the four countries– Australia, Japan, India, and the US. Dr Ravi responded by highlighting the rising activity within the QUAD due to the pandemic and vaccine diplomacy. While she is optimistic regarding the frequency of meetings, she underscored her concerns regarding India’s interests being overlooked within these meetings; thus, concrete steps, which are clearly communicated, are essential, she states. Ms Keynes also asked the panelists about the potential of a US-India digital agreement. Both panelists were in consensus regarding the risk and hesitation from the Indian side on allowing large-scale digital access. Dr Ravi highlights that there is already “a considerable push back from the Indian technology industry,” with a heavy focus on local strategic interests. Mr Nathani echoed this sentiment, stating that it may be difficult to negotiate at this point in time.

Looking towards the future of the US-India Trade Relationship

Various issues were highlighted regarding the US-India trade relationship, with the second half of the discussion looking at future steps and options for India. Ms Batra asked both panelists to expand on the current gaps within the trade realm, focusing on the lack of data and motivation in India’s decision-making. Dr Ravi echoed this concern, highlighting the lack of data and research. While new centers and research have begun to emerge in India, she shared that there is not enough “real-time” data to enact meaningful policies. Likewise, Ms. Batra also asked about the gaps in expectations in the trade relationship. Mr Nathani responded that despite having ample “synergy” and opportunities to connect through the diaspora, the two economies cannot understand one another’s “trading patterns.” India’s strong domestic lobby and hierarchical institutional structure make negotiations difficult with the US, which is far more open in its negotiation style. Thus he proposed that a more diverse group of people come together to drive successful future discussions.

Moreover, Ms Batra brought the current US political climate into the spotlight, asking the panelists their perspectives on the shifting agenda of the USTR under the Biden administration, focusing on issues such as labor and the environment. Dr Ravi viewed this shift as a new variable that only heightens uncertainty between the two nations, given the increased stakeholders. Ms Batra also directed the conversation to examine the changing role of the WTO and whether bilateral trade agreements would be the future rather than multilateral agreements. Mr Nathani responded by outlining how the WTO will play a limited role in the short to medium term, given there has been little consensus on trade, thus bilateral needs to be developed to allow for multilateral relationships to also work in the future.

Lastly, the panelists looked at non-resident senior fellow and co-author of the report, Mark Linscott’s question regarding the on-ground reality of incrementalism within the trade relationship. Dr Ravi shared her opinion on the importance of incrementalism, given that in India, despite the challenges surrounding it, small gains and detail-oriented agreements hold great value and should be the focus within this relationship.

Both panelists highlighted the immense importance of trade to both countries. As Dr Ravi points out, trade can bring about positive changes to the “real economy,” in the form of jobs and technology transfer, therefore, it must be brought to the forefront of domestic and international discussions. Furthermore, as pointed out by Mr Nathani, trade extends into our lives in an increasingly intersectional manner- from health to security. Hence, understanding the trade relationship is complex, and its solutions extend beyond mere cooperation. It requires clear communication and understanding of the various stakeholders involved. Likewise, the relationship demands an approach that is mindful of the structural and political differences of the two nations, as highlighted by the panelists. Overall, the event highlighted the current challenges that remain in the relationship, helped construct the possibilities for what can be done to expand trade opportunities for India, and paved the way for an insightful and more nuanced perspective on the US-India trade relationship.

Ayra Khan is a research assistant at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center

The South Asia Center is the hub for the Atlantic Council’s analysis of the political, social, geographical, and cultural diversity of the region. At the intersection of South Asia and its geopolitics, SAC cultivates dialogue to shape policy and forge ties between the region and the global community.

Related Content

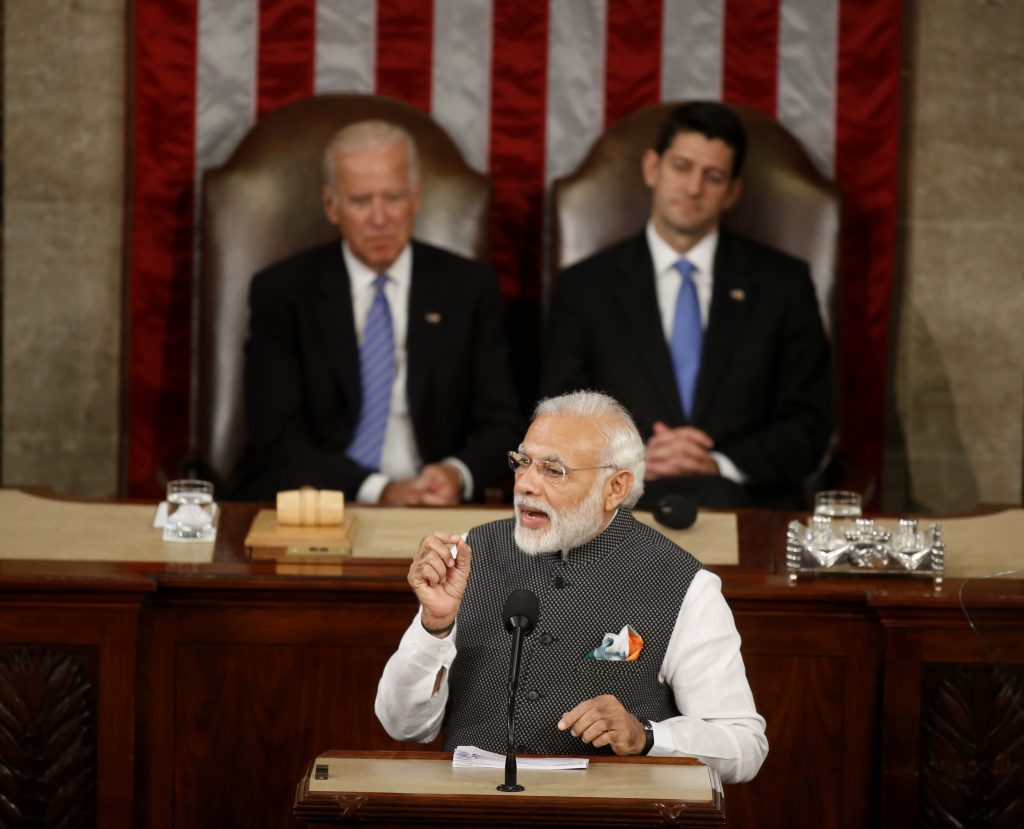

Image: U.S. Vice President Joe Biden (L) and Speaker of the House Paul Ryan look on as India Prime Minister Narendra Modi addresses a joint meeting of Congress in the House Chamber on Capitol Hill in Washington, U.S., June 8, 2016. REUTERS/Carlos Barria