Benjamin Franklin is famous as a great eighteenth century inventor and scientist, perhaps remembered most vividly for flying a kite in a storm to prove that lightning is electricity. Yet he was also one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, contributing greatly to conceptualizing the American nation as well as serving in Europe as the first United States ambassador to France.

In the book Corruption in America, Zephyr Teachout narrates the interesting story of how a development during Franklin’s stint in France exemplified the young American nation’s efforts to create safeguards against corruption.

When Franklin left Paris in 1785, French monarch Louis XVI gifted him a portrait of himself surrounded by more than four hundred high-quality diamonds, and held in a golden case. It immediately became the most expensive property Franklin owned.

Such gifts were considered part of routine state etiquette towards parting diplomats in Europe. However, the United States, just ten years old at the time and seeking to rid itself of what it saw as European decadence and moral stagnation, created an explicit rule in the Articles of Confederation, the predecessor document to the US Constitution, against such gifts. This lives on today as the Foreign Emoluments Clause, which states that “no Person holding any (government office) shall, without the Consent of the Congress, accept (any gift) whatsoever, from any King, Prince, or foreign State.”

As deposed Pakistani prime minister Imran Khan’s toshakhana (official gifts repository) scandal continues, one can do worse than to think about a young United States’ concerns about public gifts and corruption.

Corruption is often defined as the misuse of public office for private gain, but one reason that debate about corruption never ends is that the term corruption means different things to different people. Some people consider only the breaking of law by public office holders as corruption. In this narrow, legalistic sense, Khan does not appear to have been in the wrong: he is said to have declared the gifts he received from foreign governments to authorities, and paid the mandated (and heavily discounted) amount office holders are obliged to pay in order to convert gifts received in their public capacities into private property. It is from this perspective that Khan could dismiss the scandal as he did, claiming “mera taufa, meri marzi” (“my gift, my will”).

Others consider corruption beyond this narrow, transactional sense of the word, to encompass activities in which public office holders behave selfishly against the broader public interest. This perspective looks beyond whether the official followed the letter of the law to ask if he or she followed the spirit of public service. Taking this view, we must ask: did Khan act in the public interest by claiming these gifts at a discount? And was his Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) government’s stance on toshakhana policies keeping with its self-proclaimed stance against corruption?

There are two major concerns when setting toshakhana policies: first, they must be supportive of healthy relations between Pakistan and countries with whom Pakistani diplomats and national leaders interact; second, as with any other government’s function, any accruing benefits should flow to the most deserving Pakistanis. The PTI’s record was problematic on both counts.

First, Khan’s government had adopted the stance that official gifts from other countries must be kept classified in order to protect our relations with them from excessive media scrutiny and debate. This is strange, if not downright absurd. If Pakistan took a page from the United States’ Founding Fathers’ playbook, it would frame gifts as flowing to the nation by making them public and subject to parliamentary oversight. The nation would thus have no reason to suspect that these gifts are the currency of murky external influence over national leaders: making gift receipts public would glorify, rather than embarrass, the benefactor nation.

Second, by raising the amount leaders have to pay to claim ownership over an official gift to 50 percent, Khan had moved in the right direction compared to previous governments. But why stop at 50 percent? Why were public officials still allowed to benefit privately from holding office?

Imran Khan has historically discussed corruption in broad and moralistic terms: material corruption is preceded by moral corruption. Anti-corruption is the fight between haq (righteousness) and batil (evil). And so without the acceptance of blatant bribes or theft from the public, there can be no corruption. This narrative has resonated deeply with a nation ground down by decades of blatant corruption. Indeed, top members of the present coalition government have previously been indicted for the illegal retention of foreign gifts themselves.

Yet for Pakistan to move forward, Khan’s supporters and critics alike have to recognize that anti-corruption is not simply about enforcing the law and chasing money trails, but about creating rules and laws that bind rulers’ hands before the fact and stop poor behavior from occurring in the first place.

In fifty or one hundred years, whether Imran Khan dipped into the toshakhana more than he should have will be a footnote in Pakistan’s history. What will matter instead is whether, like the United States’ Founding Fathers more than two centuries ago, Pakistan is able to put a governance architecture in place that compels future leaders to hold the interests of the average Pakistani supreme in their actions in office.

Dr. Ali Hasanain is the Head of the Economics Department at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) and a non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

The South Asia Center is the hub for the Atlantic Council’s analysis of the political, social, geographical, and cultural diversity of the region. At the intersection of South Asia and its geopolitics, SAC cultivates dialogue to shape policy and forge ties between the region and the global community.

Related content

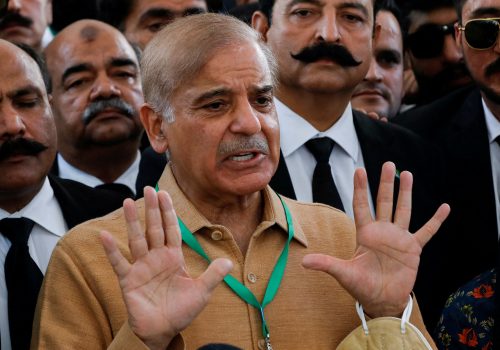

Image: Pakistan's Prime Minister Imran Khan speaks during a session at the 50th World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos, Switzerland, January 22, 2020. REUTERS/Denis Balibouse