The populist Prime Minister of Pakistan Imran Khan, who promised a “Naya (New) Pakistan” Pakistan, has been removed from office by a vote of no confidence in parliament, the first ever in Pakistan’s fraught political history. He is succeeded by Shehbaz Sharif, the younger brother of former prime minister Nawaz Sharif of the Pakistan Muslim League, Nawaz Group. Ironically, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari of the Pakistan People’s Party proclaimed “welcome back to ‘Purana’ (Old) Pakistan!” This change maintains a streak that no Pakistani prime minister has ever completed his or her full five-year term. Khan’s government has been replaced by an alliance of parties of different political stripes, glued together by their desire to oust Imran Khan. Most of them are dynasts. Most of them have been ruling the country off and on before Khan broke their oligopoly of power as the disruptive Trumpian outsider. But, in the end what put paid to his tenuous hold on power was not so much the political opposition but the withdrawal of support from the powerful Pakistan army chief General Qamer Javed Bajwa, whose intelligence agencies had enabled Khan’s victory in the 2018 elections and who now publicly took a “neutral” position.

This emboldened the opposition and led to an open break within the Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaaf of Imran Khan, already fractured by internal dissent. The Khan-military misalliance was doomed to fail as he increasingly asserted himself on the basis of his perceived appeal to Pakistani youth, retired military, and even among younger military officers belonging to a generation that knew Khan as the cricket hero who won the World Cup for Pakistan in 1992. Khan, the aging pop idol, captured the imagination of the country’s dominant demographic, its youth. With a median age of 23 years, most of the population of over 220 million is in the youth category.

Imran Khan confused his 2018 victory, aided by the military, with a genuine electoral mandate. Yet, his was a coalition government dependent on allies, who in the end deserted him. Earlier, with financial and political support from wealthy businessmen patrons like Jehangir Tareen and Aleem Khan, he cobbled together a winning combination of so-called “electables” who were themselves members of and professional turncoats in Pakistani politics, well known for always jumping on the winning party’s bandwagon. In the process, Khan alienated his hardcore PTI supporters. He came into power without a cohesive or coherent program, relying instead on slogans that harkened back to the State of Medina and promising an Islamic welfare state similar to the one Prophet Muhammad established. He personally represented a break with the dynastic politics of the past (though his party was riddled with dynasts) and his personal reputation of being uncorrupt helped him win over the youth and urban elites. But very soon he became the target of accusations that he allowed his newly acquired third wife, a spiritual guide whom he consulted before he married her, to conduct bribery directly and through her friends and former husband and his family. The Covid 19 pandemic and global inflation, among other things, added to his economic woes. He handled the Covid situation very well. But Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves went on a serious downslide, down to two months of imports. The $6 billion IMF program was effectively suspended. Foreign Direct Investment declined. Domestic inflation reached 15 percent for fuel and food. Deficit financing to fund his welfare schemes in electioneering before the next set of national polls became a drain on resources. He faced rising fiscal and current account deficits and the Pakistani rupee tumbled against the dollar. The global Covid pandemic and worldwide inflation resulting from the Russian invasion of Ukraine exacerbated his economic woes.

Khan struggled against these odds to maintain his hold on power, even as his relationship with the military deteriorated. He added to his difficulties by presenting a narrative of victimhood in which he was the target of American moves to remove him from power, citing a report by his ambassador in Washington DC about a threat from a senior State department official. This “letter” that he brandished in public, without disclosing its contents, became his proof of a conspiracy against him as a champion of Islam. Relations with the United States suffered even more. The ensuing uproar alarmed even the army, leading the army chief to declare publicly the importance of Pakistan’s relations with the United States.

The cliche in Pakistan that most civilian governments peddle is “We are on the same page“ with the army. Sometimes the military reciprocates in this charade. The reality is that they may be on the same page but are reading different books. Khan’s fate was sealed when he broke with Bajwa.

They had been drifting apart on a number of issues. Economics and trade was one issue. Bajwa saw regional connectivity, including trade with India, as critical to economic growth and growing the economic pie (with more resources available for its defense). Khan chose to cut ties with India and play to the populist Islamist gallery on the disputed territory of Kashmir. Similarly on the US relationship, the army wanted to maintain and grow that relationship since it prefers advanced Western equipment and training. The proximate cause of the split was the replacement of Khan’s apparent favorite Director General of the powerful Inter-Services Intelligence directorate (ISI), Lt. Gen. Faiz Hameed, by Lt. Gen. Nadeem Ahmed Anjum in November 2021. Imran Khan wanted to keep Hameed at ISI for some time to ensure his own re-election and there were rumors rampant that he wanted Hameed to replace Bajwa when Bajwa’s second term ended in November 2022. Khan embarrassed Bajwa by retaining Hameed for a while. He said he wanted to interview the candidates that Bajwa put up. Eventually Hameed left and Bajwa’s original choice was appointed DGISI. But the damage to the relationship had been done. Khan added to the confusion by sharing publicly that he had not yet focused on an extension for Bajwa in November this year, feeding the idea that Bajwa may have sought another extension. Not a smart move to win or retain the favor of his own patron!

Bajwa resisted the lure of an open confrontation with the prime minister in this political brinksmanship and maintained a stoic silence in public while briefing journalists and opinion leaders in private about his concerns. One such session included an elucidation by Bajwa of the damage done to foreign relations by Khan’s Trumpian disregard for facts and shoot-from-the-hip style of diplomacy that had angered friends and patrons like Saudi Arabia and China. Khan’s acolytes continued to belabor the complaint that US President Joseph Biden had failed to telephone call after taking over the White House.

Against this backdrop, the opposition took the battle to parliament and with the help of breakaway segments of Khan’s coalition launched a vote of no confidence that Khan tried to deflect with an unconstitutional move to disband parliament. The Supreme Court overturned Khan’s gambit to retain power. Khan lost the confidence vote in parliament but failed to show up himself, getting most of his party loyalists to resign their seats. This move in itself may well allow the new government, if it so chooses, to stage quick by-elections, build on their current momentum and consolidate their hold on power.

Now, Khan is relying on street demonstrations to show his strength. But without the institutional backing of the powerful army, he faces an uphill task as a new Ancien Regime tries to pull the country of its economic hole. Khan will be taking a huge risk by creating street unrest and inciting the urban youth and middle class against the army. If the economy continues to tumble and political and social unrest grows, the situation may become ripe for a military intervention again. Not something that most thinking Pakistanis nor even sagacious military commanders desire, given their experience of past military rule.

A better scenario would include a serious effort to rebuild the economy, revive the IMF program, reinvigorate foreign direct investment, and then have a vigorous political campaign in which Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif can point to his successes and Imran Khan can make his case for reinstatement. Prime Minister Sharif has a reputation for getting things done in the Punjab. He now has an opportunity to perform on a larger stage. His first speech in parliament gave the right signals of unity not division and bringing along the less powerful provinces. Meanwhile, Pakistanis will be keeping an eye on the army, under a new chief, to provide security for a free and fair elections, without putting its fingers on the scale of public opinion.

Shuja Nawaz, Distinguished Fellow, South Asia Center, Atlantic Council, Washington DC. Author recently of The Battle for Pakistan: The Bitter US Friendship and a Tough Neighborhood (Penguin Random House, and Liberty Books, Pakistan, 2019, and Rowman and Littlefield 2021). www.shujanawaz.com

The South Asia Center is the hub for the Atlantic Council’s analysis of the political, social, geographical, and cultural diversity of the region. At the intersection of South Asia and its geopolitics, SAC cultivates dialogue to shape policy and forge ties between the region and the global community.

Related content

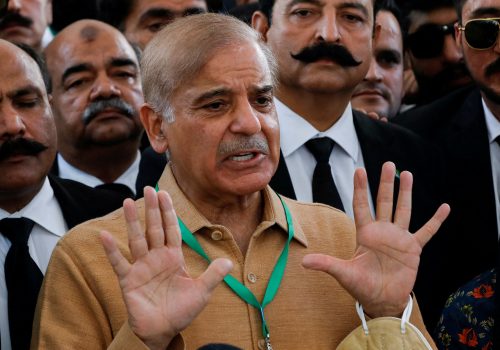

Image: Cricket star-turned-politician Imran Khan, chairman of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party, spoke to journalists in Islamabad after casting his vote in Pakistan’s general election on July 25. Khan declared victory on July 26, but his rivals alleged widespread vote rigging. (Reuters/Athit Perawongmetha)