Zelimkhan Khangoshvili was walking through a Berlin park on his way home from midday prayers at a local mosque on August 23, 2019 when his past finally caught up with him. A Georgian national and ethnic Chechen who had fought in Chechnya’s post-Soviet wars of independence and the 2008 Russo-Georgian War, Khangoshvili was trailed by a Russian on an electric bicycle who shot him twice in the head and once in the shoulder, killing him instantly. The assassin was arrested by German authorities within a few hours of the murder, having been spotted throwing his gun and wig into a nearby river.

This operation was shocking in its brazenness, but it was hardly unprecedented. On the contrary, it fitted neatly into a broader pattern of international attacks perpetrated by Kremlin agents in recent years. Targeted assassinations are nothing new in the intelligence world, but the air of plausible deniability exhibited in the past seems to have disappeared today. What’s more, killings like the Berlin attack fly in the face of Russia’s international commitments and cause significant damage to the Russian government’s credibility. Nevertheless, the death toll continues to mount.

Crucially, these murders demonstrate the Kremlin’s readiness to hunt down foes across the globe with little regard for the laws of host countries. They allow Russia to intimidate perceived traitors while sending a chilling message of defiance to the country’s international adversaries, and reflect the increasingly hostile dynamic between Russia and the West since the 2014 invasion of Ukraine. This trend has not gone unnoticed. Indeed, the Russian appetite for state-sanctioned assassinations has now become so pronounced that lawyers in the MH17 trial, which is currently underway in the Netherlands, recently cited it as the key reason to maintain the anonymity of witnesses.

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

Calder Walton, the Assistant Director of Harvard University’s Applied History Project and a Fellow of the Intelligence Project, says this pattern of Russian attacks may be a strong example of a troubling new reality. “Are we now in a situation in international relations where assassination is becoming much more of an open or, dare I say it, routine phenomenon in world affairs? It does seem that there’s been a change,” he notes.

As the United States government’s January 2020 killing of Iranian general Qasim Soleimani demonstrated, the Kremlin does not have a monopoly on targeted assassinations on foreign soil. However, while the US has made no effort to disguise its responsibility for the attack that killed Soleimani or similar drone strikes, there’s a substantive difference in the Kremlin’s goals and targets.

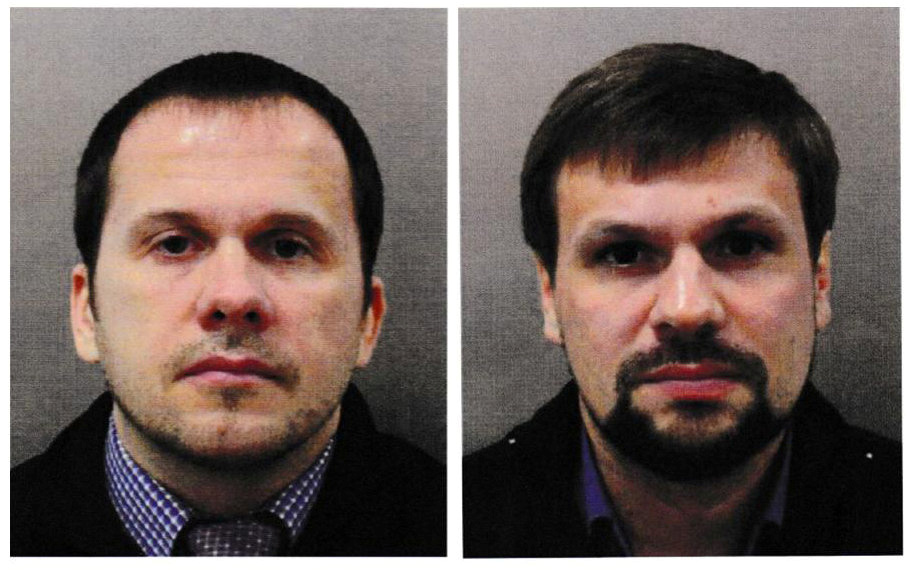

Many victims of Putin’s assassins serve as useful symbols of what happens to anyone accused of betraying or otherwise cheating the Kremlin. Sergei Skripal, who survived being poisoned by two Kremlin agents during a spring 2018 operation in Salisbury, England, had earlier been imprisoned by the Russian government for slipping state secrets to the West. Meanwhile, the 2015 poisoning of Bulgarian Emilian Gebrev has been linked to his role in the arms trade, where he frequently foiled Russian attempts to make deals in Africa and Asia.

These assassination attempts do not always end in the death of the target. Both Skripal and Gebrev survived, as have numerous other targets, suggesting a decline in professionalism as Russia seeks to deploy greater numbers of assassins abroad. Still, even unsuccessful operations may have their uses as far as the Kremlin is concerned. “I think there’s also an element of sticking two fingers up at Western countries here, as if Russia is saying ‘we don’t even really care if this works or not,’” Walton says.

A key question is whether such sloppiness is intentional or not. “I think it was a little bit of a sloppy tradecraft with Skripal,” says Atlantic Council Senior Fellow Alexander Vershbow, who served as the US ambassador to Russia from 2001-2004. “But they also don’t seem to care that much. It enhances the fear they want to instill in their enemies. The brazenness, I think, is what’s most striking these days. And that they actually want us to know that they did it.”

Eurasia Center events

Soviet hit squads had been a routine feature of the first Cold War. Following a brief lull during the 1990s, President Putin reopened the door to Kremlin assassinations on foreign soil when he backed a new Russian law in 2006 authorizing extrajudicial killings abroad under the guise of “combating extremism and terrorism.” The troubling nature of this law was raised early on by London-based Russian defector Alexander Litvinenko, who warned that it could be used to target Putin’s personal enemies. Within months, Litvinenko was dead. The use of a rare radioactive poison to kill Litvinenko turned his death into a protracted public execution that served the Kremlin’s purposes admirably. It left exiled opponents of the Putin regime in no doubt of the fate that might await them, while allowing Moscow to protest its innocence.

Putin’s use of international assassinations has escalated significantly in the years following 2014. The Russian seizure of Crimea six years ago and subsequent military intervention in eastern Ukraine are watershed moments in the history of Moscow’s post-Soviet relations with the Western world. Ever since, the Kremlin has engaged in an escalating campaign of hybrid hostilities against the West. Targeted assassinations are only part of this global confrontation, which also includes everything from cyber-attacks and disinformation campaigns to election meddling.

Russia has already paid a price for its increasingly aggressive actions, with the post-2014 spree of Kremlin-linked killings proving particularly damaging to the country’s international standing. The US government expelled 60 Russian diplomats and closed a Seattle consulate in 2018 in response to the Skripal poisoning, something shown by Walton’s research to have had a serious effect on the capabilities of Russian services to operate abroad. The US and its partners now need to increase the pressure on the Kremlin over these killings. Sanctions and expulsions should remain part of the solution, but they obviously haven’t proven a strong enough deterrent to stop further waves of attacks.

With the Kremlin’s use of assassins throughout the Western world in danger of becoming the new normal, fresh options should be explored that will introduce escalating costs on Putin’s regime while also galvanizing public opinion. The Kremlin clearly sees these killings as an effective way of intimidating opponents and displaying its impunity on the international stage. If the West wants to regain the initiative in the hybrid war against Russia, targeting Putin’s not-so-secret assassins might be a good place to start.

Doug Klain is a program assistant at the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center. He tweets @DougKlain.

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

Image: Alexander Petrov and Ruslan Boshirov, who were formally accused of attempting to murder former Russian intelligence officer Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia in Salisbury, are seen in an image handed out by the Metropolitan Police in London, Britain September 5, 2018.