June 29, 2023

How to advance women’s rights in Afghanistan

Top lines

- Terrorist groups and extremist ideology will fill the social vacuum created by the erasure of Afghanistan’s women.

- Providing Afghan women with rights and opportunities must be at the top of the regional and global security agenda.

- Shifting from humanitarian aid to economic development projects could give the West leverage over the Taliban and is better for the long-term health of the country.

Roya Rahmani and Melanne Verveer discuss Afghan women as the way forward and how the international community should engage now, nearly two years after the fall of Kabul. (Rahmani and Verveer’s biographies are below.)

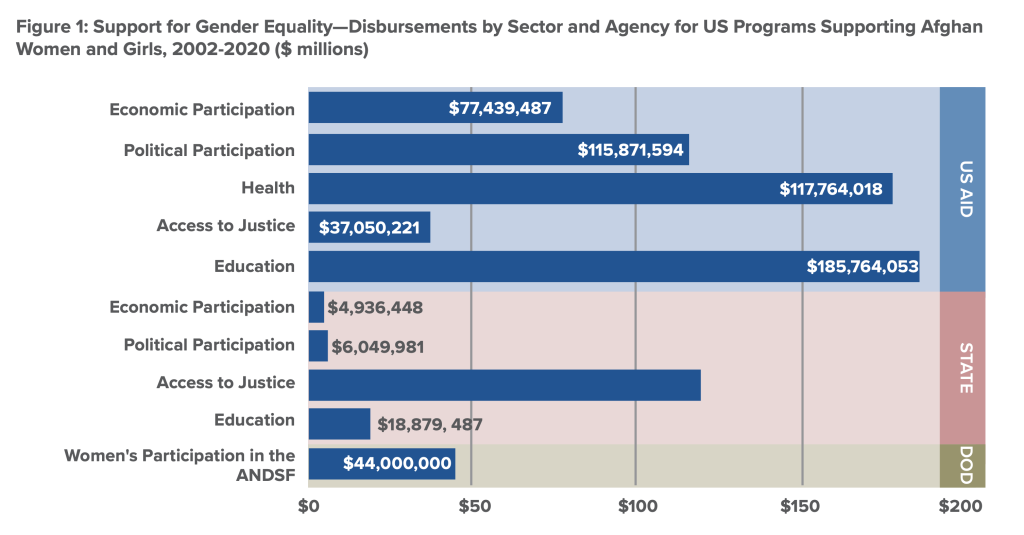

Worth a thousand words

The diagnosis

- During the twenty-year US intervention in Afghanistan, metrics gauging women’s health and education and women’s presence in local and national politics all improved.

- Since August 2021, those gains are at risk of reversal. Women’s rights have deteriorated, and the international community’s efforts to engage with the Taliban and support Afghan women have been unsuccessful.

- Carrots such as international recognition and sticks such as public condemnations and threats of NGO withdrawal have proven ineffective, yet these strategies are endlessly recycled.

- The international community and multilateral organizations remain disengaged from strategic policymaking, passively supplying humanitarian aid without directing funding toward strategic future goals.

- The West lacks both knowledge of and leverage over Afghanistan’s leadership.

The prescription

Establish a more robust forum for international consultation. Ad hoc consultations aren’t working: Regular meetings of experienced representatives need to be established. The core group should include the United States, the United Kingdom, several European Union countries, key Islamic countries such as Qatar and Indonesia, and NGO and multilateral representatives with on-the-ground knowledge.

Keep security strategy at the heart of engagement. Place the security implications of women’s oppression on every agenda of every meeting. As society disintegrates further, more room is created for terrorist groups to flourish, as shown by the growth of the Islamic State group’s offshoot ISIS-K.

Send female diplomats and delegations from Islamic countries. Bilateral engagement should feature overwhelmingly female delegations and prioritize consultative meetings with Afghan women to hear their perspectives on community needs. Furthermore, Islamic countries and organizations need to be key partners in the West’s efforts for humanitarian relief and overall engagement. Not only do they have the expertise and credibility needed to engage and advise on practical mechanisms for the implementation of programming, but direct engagement between more moderate Islamic countries and the Taliban could be influential. Qatar is a particularly important partner because of its role as an international interlocutor with access to the highest ranks of the Taliban.

Use aid as leverage by strategizing beyond immediate relief. Shifting Western aid from a focus on emergency humanitarian assistance to more sustainable, large-scale economic development initiatives reorients the sense of dependency from the people to the Taliban regime, which also creates a new potential point of leverage for the international community. Donors should craft aid distribution networks that are more local and grassroots, and use creative approaches to keep women at the center of all aid initiatives. This could mean developing aid programs specifically for widows, forming local partnerships that explicitly require the adoption of female-specific tasks.

Take advantage of the internet, and prioritize development projects that keep Afghans connected. Unlike during the 1990s Taliban regime, most Afghans have a mobile phone, internet access, and social media. These new tools must be used proactively by the international community to disseminate key information about the Taliban’s failures, coordinate mobilization, and provide educational resources. Development projects focused on connectivity and subsidizing local media will help keep information flowing into and out of Afghanistan.

Bottom lines

A personal note

“While the regime stays in power, concrete steps have to be taken within the current context to counteract urgent security threats, provide critical aid, get children back in schools after a year-and-a-half gap, and address other imminent issues. Recycling policies from 1996 will not work. After twenty years of societal transformation, Afghanistan is a fundamentally different place.

Without innovation, no progress can be made.

Similarly, without engagement, no progress can be made.

Like other Afghan women, my entire life has been shaped by one conflict after another. Born on the eve of the Saur Revolution, I lived through the Soviet invasion, the Civil War, and the Taliban’s 1990s rule. Until the intervention, each chapter that unfolded was heartbreak anew. The revival of democracy and freedom brought hope. The Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan in 2021 was even more painful and shocking than anything before because it shattered an era that had been characterized by so much progress.

I have fought for women’s rights my whole life: the right to go to school and have an income, a voice, and autonomy. I am deeply disturbed and angered by what Afghan women are currently experiencing, and I share the instinctive desire to disengage from Afghanistan entirely given the Taliban’s inhumanity—or at the very least condition aid on women’s rights. However, this does nothing to address the ongoing humanitarian crisis. People simply suffer. Ultimately, we must be doing all that is possible to save lives. It is my hope that this report can help to make the road ahead clearer. The futures of so many Afghans—young girls banned from school, women imprisoned in their own homes, and an entire generation whose dreams have been crushed—depend on what we do now.”

—Roya Rahmani

Like what you read? Check out the full report here:

Ambassador Roya Rahmani has over twenty years’ experience working with governments, nongovernmental organizations, and the private sector. She currently serves as a distinguished fellow at Georgetown University’s Global Institute for Women Peace and Security, the chair of Delphos International LTD, a global financial advisory firm based in Washington, DC, and a senior adviser at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center. Rahmani was the first woman to serve as Afghanistan’s ambassador to the United States of America and held the role from 2018 to 2021. She was also the first woman to serve as Afghanistan’s ambassador to Indonesia, serving from 2016 to 2018. She holds a bachelor’s degree in software engineering from McGill University and a master’s degree in public administration from Columbia University.

Ambassador Melanne Verveer is executive director of the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace & Security, and board director at the Atlantic Council. Verveer previously served as the first US Ambassador for Global Women’s Issues, a position to which she was nominated by President Barack Obama in 2009. She coordinated foreign policy issues and activities relating to the political, economic and social advancement of women, traveling to nearly sixty countries. She worked to ensure that women’s participation and rights are fully integrated into US foreign policy, and she played a leadership role in the administration’s development of the US National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security. President Obama also appointed her to serve as the US Representative to the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women.

The South Asia Center (SAC) is the hub for the Atlantic Council’s analysis of the political, social, geographical, and cultural diversity of the region.

At the intersection of South Asia and its geopolitics, SAC cultivates dialogue to shape policy and forge ties between the region and the global community.

Related content

Image: Afghan women attend the inauguration of a women's library in Kabul, Afghanistan, August 24, 2022. REUTERS/Ali Khara