Alyaksandr Lukashenka’s call on January 10 for closer integration with Russia “without any obstacles whatsoever” is just one example of the beleaguered Belarusian leader’s frantic and increasingly desperate efforts to please Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Another example is Belarus acquiescing to Moscow’s long-standing demand that it export refined petroleum products via Russian ports-something Lukashenka had been resisting for years. Yet another was an agreement allowing Russian’s National Guard troops to operate in Belarus.

The fact that Lukashenka has no place to turn other than Russia has been obvious since the current crackdown on protesters began in August 2020 following a disputed Belarusian presidential election. The Lukshenka regime’s violent response to pro-democracy protests across the country has foreclosed any possibility of rapprochement with the West.

Less obvious has been what Putin would do with this newfound leverage over his wayward client.

Prior to August 2020, the Russian-Belarusian relationship was largely frozen in suspended animation. Putin viewed the relationship as imperial in character and bristled at the disobedience of his perceived junior partner. Lukashenka viewed it as transactional and sought to monetize the relationship. He also flirted with the West when Moscow cut subsidies.

The two men are widely believed to detest each other, but were nevertheless stuck in a dysfunctional marriage that had survived on codependency, mutual convenience, and inertia. This is no longer the case. Putin now clearly has the upper hand. But whether the Kremlin leader can translate that into achieving Russia’s strategic goals in Belarus remains fluid and unclear.

Belarus occupies a central place in Russian strategic thinking and is an essential part of what Moscow considers its “strategic depth,” that is, the existence of dependent satellite buffer states on its Western border. Any move Moscow makes, whether shoring up Lukashenka or replacing him with a more pliant figure, will aim to preserve this “strategic depth.”

The most visible sign so far that the Putin regime is considering looking beyond Lukashenka was a leak in late December 2020 to the Russian investigative news site The Insider of documents allegedly from the Kremlin’s Department for Interregional and Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries. That office, led by Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) General Vladimir Chernov, formulates policy in the former Soviet Union.

The documents note “a growing massive and deep-rooted rejection” of Lukashenka, not only among the Belarusian public but also among the nomenclatura. The leak outlines a policy of forcing the Belarusian leader into constitutional reforms that would establish a parliamentary republic. Moscow would then seek to establish a pro-Russian political party along with accompanying information resources including traditional media, YouTube channels, and Telegram channels, in order to assure Moscow’s control of the newly empowered parliament.

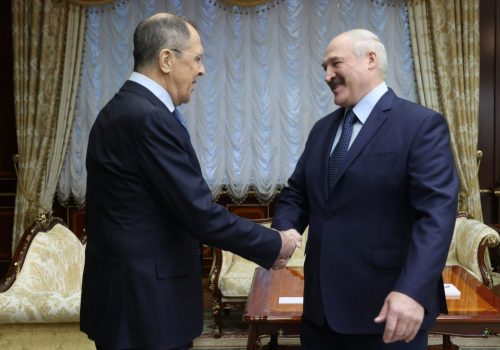

It is unclear if the leak signals a real change in policy or whether it is a psy-op designed to secure Lukashenka’s cooperation. One thing is clear-it did not happen in a vacuum. Moscow has been pressing Lukashenka to implement constitutional reforms, most notably during Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov’s visit to Minsk in November 2020.

Coverage of the recent leak has been accompanied by what appears to be an emerging consensus among Russian commentators, including regime technocrats as well as strident nationalists, that Lukashenka has outlived his usefulness.

Andrei Kortunov, the director of the Russian International Affairs Council who is viewed as a foreign policy liberal, told Voice of America “Putin realizes Lukashenka has turned into a lame duck whose term is expiring and that the political transition in Belarus is already going on. The objective is not to stop it but to make it less painful and more manageable.”

Likewise, economist Yevgeny Gontmakher told Moskovsky Komsomolets that the situation in Belarus “very much recalls the Polish events of the 1970s and 1980s which ended with the collapse of the socialist system throughout Central Europe and then with the disintegration of the USSR.”

If Russia does not change course, he added, “it is obvious that whoever comes to power in Belarus after Lukashenka will not be inclined to support any partnership with Russia, let alone in the framework of a union state.”

Gontmakher also told VTimes that if Lukashenka remains, external sources of financing will be closed and Russia will be responsible for “the support of 9.5 million Belarusians.”

The growing chorus also includes hardliners. Political commentator Aleksandr Nosovich, who is known for his harsh broadsides against the Baltic states, argued in an article in Rubaltic.ru that reforms designed to weaken or remove Lukashenka are necessary. But he added that Moscow needs to be vigilant about preventing the West “from fishing in the murky waters of constitutional reform.”

Eurasia Center events

Talk of a soft coup to replace Lukashenka and mollifying social unrest through constitutional reforms reflects a more nuanced approach that many observers have noted in Moscow’s efforts to control the former Soviet space.

But more blunt and hardline approaches also remain on the table.

In a confidential unpublished report, the Minsk-based Center for Strategic and Foreign Policy Studies wrote that a December 25 meeting of Russia’s Security Council discussed a “tough scenario” that included “intensified protests (this time driven by economic motives) and Lukashenka’s violent overthrow.”

Under this scenario, the Russian armed forces would “play the main role, including sabotage and reconnaissance groups operating under the guise of private military companies and private security companies.”

To be sure, Putin could still stick with Lukashenka. His default setting tends to be conservative and risk averse, unless he believes a client state is in imminent danger of slipping out of Russia’s orbit. The Belarusian leader’s blatant efforts to please Putin appear designed to appeal to this instinct.

What the debate over the Kremlin’s Belarus strategy illustrates is that Russia has few good options. Removing Lukashenka risks setting yet another precedent that a post-Soviet leader can be toppled by a social uprising. Sticking with him places Moscow firmly in opposition to a growing majority of Belarusians.

Brian Whitmore is a nonresident senior fellow at The Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center and an Adjunct Assistant Professor at The University of Texas at Arlington.

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

Image: Russian President Vladimir Putin and Belarus President Alyaksandr Lukashenka pictured during a 2019 meeting in Sochi. (Sergei Chirikov/Pool via REUTERS)