As the new Biden administration attempts to rehabilitate relationships with US allies and partners, it faces two stark options on the way forward economically. The first approach is quite conventional: treating trade as a mostly separate issue without regard to diplomatic or security concerns. The second is to fold its trade policy into a larger overall approach to US global interests and geopolitics. If the Biden administration chooses a conventional approach to trade policy, it will not only deprive itself of a powerful instrument to shape international relations, but also put US interests and the Western liberal order at a disadvantage.

The transatlantic relationship is one of the most important partnerships the United States must solidify in the coming years. China is competing with the United States to shape the world according to its own vision of order, based on the values and interests of the Chinese Communist Party. The way the United States and the European Union (EU) interact in the economic domain will affect the extent to which the Atlantic alliance can establish a global order in which the vital interests of liberal democratic powers are secure. This alliance is about Western unity, not just military-strategic cooperation.

The key challenge for the United States will be to structure the Euro-American economic relationship with an eye to this emerging Chinese order. This will require re-examining the effects that evolving transatlantic trade and investment dynamics have had on the strategic dimensions of the alliance.

Increasing economic interdependence may improve diplomatic relations, but that is not a given. In fact, the ever-increasing volume of trade and investments across the Atlantic has not strengthened strategic ties—and perhaps has even weakened them. Nor has growing US-Chinese economic interdependence brought about an alignment of political and strategic interests across the Pacific. Europe and the United States have been at loggerheads economically for more than half a century, if not longer. Contentious issues have ranged from chlorinated chicken, genetically modified organisms (GMOs), and hormone beef, to digital tax and data privacy; from steel and gas to audiovisual markets; and from financial sanctions to cars and airplanes, among others. These flashpoints have emerged because of the deepening economic link across the Atlantic and have threatened to sour diplomatic relationships rather than reinforce them.

These trade conflicts have driven a wedge between Europe and the United States, weakening the strategic potential of the transatlantic relationship. Even though many European governments appear willing to engage the United States despite these conflicts, European populations are divided, in part as a result of their strong reactions to these trade disputes. When Europe’s populations are confronted with the negative aspects of US business practices and economic globalization, they can become disenchanted with all facets of US engagement.

The export of American popular culture may also actually undermine US strategic interests. In Europe, the presence of American cultural products and business has triggered violent protests and stirred hot emotions. French farmers attacked McDonald’s in 1999, Spanish protesters destroyed Levi’s stores in 2010, and Italians nowadays fear the disruptive effect of Amazon on their traditional communities, just to give a few examples. Such protests are not without political consequences.

The prospect of more transatlantic trade in the last decade was met with similar reactions. The EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) and Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) negotiations became rallying points for anti-globalist movements, while reinforcing the political base of far-left and far-right movements. Some have argued that the socio-economic consequences of globalization have undermined the political center, giving more room to populist parties that are often both anti-Atlanticist and Eurosceptical. The weaker the political center becomes, the narrower the margin for allied diplomacy and Western unity in the face of China’s emergence.

In confronting the rise of China, the United States and the EU must establish a Western vision of global order that provides security to liberal democracies before considering ambitious lists of separate agenda items. Establishing a high-level dialogue on overall political objectives should be the first priority, as well as developing a joint understanding, or strategic concept, of how the United States and the EU can use their economic power to strengthen the Western order. Such a dialogue needs to include a critical assessment of the assumptions that have informed the Western approach for decades but may have ended up weakening the transatlantic bond.

Instead of striving for greater mutual economic engagement, the United States and the EU, perhaps together with Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) partners, should seek a common approach to third parties. This could include the creation of joint rules on strategic economic issues such as foreign direct investment, technical norms, information security, banking rules, and so forth. Those concrete policy issues, however, are a second step and should not be confused with strategy. Reaching that shared vision will be the most important step both sides of the Atlantic can take to put their relationship back on track.

Elmar Hellendoorn is a nonresident senior fellow in the GeoEconomics Center and the Future Europe Initiative. He provides strategic advice and insight on the nexus of geopolitics, global markets, and technology. For over a decade, he was an advisor across the Netherlands’ government, where he pioneered economic security as a policy theme.

Further reading

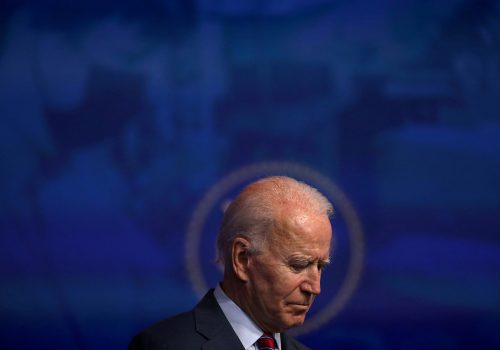

Image: REUTERS/Francois Lenoir