Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has left it with few friends, but Azerbaijan is an important exception. In fact, Moscow and Baku are effectively allies now. Just two days before the February 2022 invasion, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev signed a wide-ranging political-military agreement, following which Aliyev declared that the pact “brings our relations to the level of an alliance.” A few months later, Azerbaijan signed an intelligence-sharing agreement with Russia.

This has proven catastrophic for Armenia, which has maintained close security ties with Russia since joining the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) in 1992. In September 2022, Azerbaijan launched what the European Parliament called a “large-scale military aggression” against Armenia and, according to Armenia’s foreign minister, took over 150 square kilometers of Armenian territory. But the CSTO—to which Azerbaijan does not belong—refused to intervene on Armenia’s behalf. Washington stepped in to broker a ceasefire, and the European Union (EU) followed suit by sending a monitoring mission to the Armenian-Azerbaijani border, much to Russia’s and Azerbaijan’s discontent.

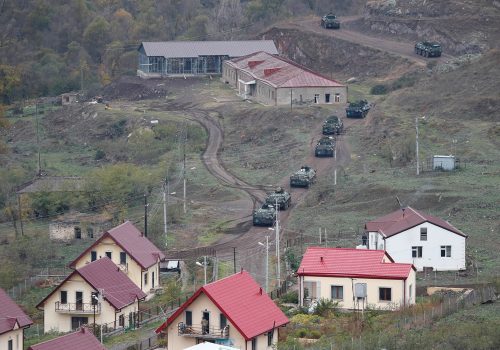

The Putin-Aliyev partnership has also spelled disaster for the breakaway republic of Nagorno-Karabakh, whose remaining 120,000 ethnic Armenians live under Russian protection after Azerbaijan’s 2020 offensive to reclaim the territory. Forty-four days and thousands of deaths later, Russia brokered a ceasefire stipulating the five-year deployment of 1,960 Russian armed peacekeepers along the line of contact in Nagorno-Karabakh and in control of the “Lachin Corridor,” the only road linking it to Armenia. At the time, analysts opined that Putin’s imposition had cemented Russia’s role in the region. According to the decree authorizing the deployment, Russia’s reason for sending peacekeeping troops was to “prevent the mass death of the civilian population of Nagorno-Karabakh.”

But the deployment has not prevented Azerbaijan from continuing to try to expel ethnic Armenians from what’s left of Nagorno-Karabakh. Last December, a group of Azerbaijanis set up a roadblock along the Lachin Corridor claiming to advocate for environmental rights in the region. But the roadblock in effect slowed the flow of goods into Nagorno-Karabakh, creating a humanitarian crisis. The United States and the EU, as well as Human Rights Watch and others, have called for Azerbaijan to unblock the Lachin Corridor. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) has ordered Azerbaijan to do the same.

Instead, Azerbaijan solidified the blockade by installing an armed checkpoint at the mouth of the Lachin Corridor, thus effectively seizing control over it. The move was further condemned by the United States and EU, and led Armenia to seek renewed intervention from the ICJ. Russia issued tepid statements and then replaced its peacekeeping force commander in Nagorno-Karabakh. But such a fundamental change in the regime over the Lachin Corridor could not possibly exist without approval—however tacit—from the Kremlin. Video footage taken last month purports to show Russian peacekeepers accompanying Azerbaijani forces to install a concrete barrier near the checkpoint and hoist an Azerbaijani flag in adjacent Armenian territory.

Since the blockade began, traffic along the Lachin Corridor has been reduced to an all-time low. This makes it more difficult for essential humanitarian aid to pass into Nagorno-Karabakh. In the last seven months, Nagorno-Karabakh has turned into an open-air prison, with ethnic Armenian inhabitants increasingly deprived of food and medicine, and energy resources almost entirely drained. They may soon be forced to flee their ancestral homeland for good just to survive.

What the United States should—and shouldn’t—do

In May, Aliyev demanded the surrender of Nagorno-Karabakh authorities, suggesting that he might offer them amnesty should they accept Azerbaijani rule. Oddly, the US State Department praised Aliyev’s remarks on amnesty, glossing over other parts of his speech in which he threatened violence if the authorities did not surrender: “[E]veryone knows perfectly well that we have all the opportunities to carry out any operation in that region today… Either they will bend their necks and come themselves or things will develop differently now.”

But Washington’s seemingly tactful acquiescence to Azerbaijan’s growing aggression against Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh in fact hurts US efforts to curb malign Russian influence and end Moscow’s war on Ukraine. The Russo-Azeri pact provides for enhanced economic ties, including in the gas and energy sectors, and has proven successful in helping preemptively circumvent Western sanctions against Russia. A deal between Baku and Brussels in July 2022 to double the flow of gas to Europe to wean it off Russian gas was soon followed by a deal in November 2022 between Baku and Moscow to increase gas imports from Russia to enable Azerbaijan to meet its new obligations to Europe.

In May, Russia and Iran agreed to complete a railroad that would link Russia to the Persian Gulf through Azerbaijan, thus providing a route through which Iran can directly send Russia more weapons and drones. One week later, during a summit of the Eurasian Economic Union, in which Aliyev participated as a guest for the first time, Putin stated that cooperation on developing this North-South railway is carried out “in close partnership with Azerbaijan.” Baku knows it can play both sides because it has backing from Moscow, while the West is blinded by non-Russian energy imports and dreams of regional stability.

If the West seeks to reduce tensions in the South Caucasus, it needs to step up its pressure on Azerbaijan. In the short term, this might include the threat of sanctions in response to further military action against Armenia and the continued refusal to unblock the Lachin Corridor, as well as lending support to Russia. By law, Azerbaijan cannot receive US military or foreign assistance unless it eschews military force to solve its disputes with Armenia, but the White House keeps letting Azerbaijan off the hook by waiving Section 907 of the Freedom Support Act and sending millions of dollars in military aid to Baku. Washington should treat Baku’s actions against Armenia as attempts at coercion, just as it does with Russian aggression against Ukraine.

For its part, Armenia has sought to unwind some of its security arrangements with Russia. Yerevan has refused to host CSTO military drills, send a representative to serve as CSTO deputy secretary general, sign a CSTO declaration to provide defense aid to Armenia, or accept the deployment of a CSTO monitoring mission in lieu of the EU-led mission. Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has even threatened to terminate or freeze Armenia’s CSTO membership.

Even so, the West cannot reasonably expect Armenia to leave the CSTO and break with Russia without significantly helping Armenia diversify and mitigate its security, energy, and economic reliance on the Kremlin. As part of this, the United States may want to consider inviting Armenia to become a Major Non-NATO Ally. Washington should provide training and equipment to enhance Armenia’s defense capabilities and help it develop a more robust and independent security apparatus. The United States could also push forward on the prospect of building a small modular nuclear power plant in Armenia, providing an incentive for Armenia to decide against partnering with Russia on energy.

The West has stepped up its diplomatic efforts to facilitate a peace treaty between Armenia and Azerbaijan, which is good, but these efforts should not come at the cost of abetting the unfolding humanitarian disaster in Nagorno-Karabakh. Now is the time to compel Baku to cease its bellicose rhetoric and consent to an international presence in Nagorno-Karabakh to mediate dialogue with residents there and promote a more meaningful transition from war to lasting peace.

Sheila Paylan is a human rights lawyer and former legal advisor to the United Nations. She is currently a senior fellow in international law at the Applied Policy Research Institute of Armenia.

Further reading

Tue, Jul 20, 2021

Infrastructure cooperation could hold the key to Armenia’s future security

UkraineAlert By

As the South Caucasus looks to move on following last year's Nagorno-Karabakh War, shared infrastructure projects could help foster greater regional stability and improve the chances for a sustainable peace.

Fri, Nov 13, 2020

Peace at last? Assessing the ceasefire in Nagorno-Karabakh

New Atlanticist By Andrew D’Anieri

After six weeks of warfare, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Russia agreed to a peace deal on November 10 that seems to be more durable than prior agreements. The war leaves Armenia and Azerbaijan with dramatically different domestic situations and a new regional security order, with Russia and Turkey as major players and the United States and Europe on the periphery.

Mon, Nov 9, 2020

Nagorno-Karabakh: An unexpected conflict that tests and perplexes Iran

IranSource By Borzou Daragahi

More likely than not, a resurrection of a decades-old war on Iran’s sleepy northern border between two countries friendly to Iran was not high on the agenda of imminent threats—if on the list at all.

Image: Russian President Vladimir Putin shakes hands with Azeri President Ilham Aliyev ahead of a meeting of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) leaders in Saint Petersburg, Russia, December 26, 2022.