The Biden administration has taken a noticeable step back from economic statecraft in the Middle East as part of a larger trend of disengagement from the region. This move has wide ramifications: It has jeopardized US efforts to counter illicit finance globally and has left a vacuum that US adversaries—particularly China—are eager to fill.

For roughly two decades, cooperation on sanctions and anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) served as a cornerstone of US relations with the countries in the Middle East, particularly in the Gulf. Over that time, successive US administrations invested heavily in bolstering institutional capacity to identify and disrupt terrorist financing in the Middle East. The United States provided technical assistance to local financial regulators and law enforcement partners and encouraged them to comply with international standards and best practices on AML/CFT. Washington has also supported efforts to strengthen policies and enforcement mechanisms needed to fight financial crime, with the goal of building sustainable, effective partnerships in the region that could enhance the scope and power of its own sanctions programs and AML/CFT efforts.

Years of deep collaboration proved to be more than just diplomatic show—the United States took coordinated action with Qatar against a network of Hezbollah financiers, stood up a Gulf-wide coalition to formalize cooperation on countering terrorist financing, and worked jointly with the Iraqi government to prevent leaders of the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham from accessing the global financial system.

Despite assurances from the Biden team that the United States remains committed to the Middle East, however, US engagement—and with it, US influence—is waning. The changing international playing field, with Russia’s war in Ukraine and the United States’ simmering tensions with China, has driven much of this change. Washington has limited bandwidth to prioritize Middle East policy, even on issues like AML/CFT and sanctions that once drove the regional agenda. And clumsy missteps and miscalculations under the current White House, such as US President Joe Biden’s widely criticized visit to Saudi Arabia last year, have likely reinforced this geopolitical realignment.

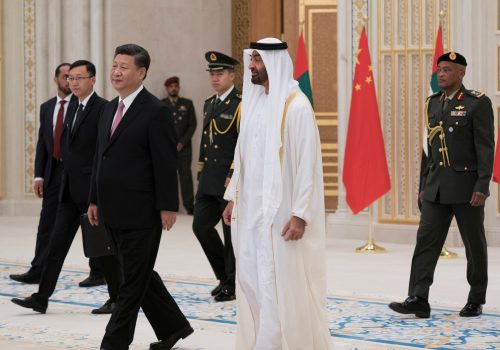

Beijing waits in the wings

Ironically, as the Biden administration rebalances its strategic priorities to focus on allies in the Asia-Pacific region—with the hopes of countering China—it has left the back door unguarded in the Middle East. China has stepped in to fill the void, building on its trade and investment-centered international playbook but with none of the same commitment to international norms and standards surrounding counter-illicit finance that the United States demands of its allies. It’s a development that further weakens US relationships in the Middle East but also puts US national-security interests at stake.

Most notably, China’s recent diplomatic outreach to the region has chipped away at US geopolitical leverage in the Middle East. For example, in March, China brokered a deal in which long-standing rivals Saudi Arabia and Iran agreed to restore relations. While it remains to be seen how committed Riyadh and Tehran are to rapprochement over the longer term, Beijing’s role in brokering the deal has elevated its diplomatic profile in the region and sidelined Washington in the process.

The deal also raises important questions about whether the Biden administration will be able to maintain a sufficiently broad coalition against Iran, as Saudi Arabia is one of the coalition’s key members. With no signs of progress on talks to reenter the landmark Iran nuclear agreement, the United States will continue to rely on sanctions to try to force change in Tehran. But China’s diplomatic rise—and its role in these talks—may weaken the effectiveness of US sanctions on Iran, as isolating Iran from the global economy becomes more difficult.

This is already happening: For instance, the Treasury Department recently sanctioned a China-based network for selling and shipping aerospace components to Iran that could be used in unmanned aerial vehicles. One Iranian company receiving the parts produces a type of unmanned aerial vehicle that has been exported to Russia for use in the invasion of Ukraine. Procurement networks like these will be increasingly difficult to target effectively as China extends its reach in the Middle East.

Officials in the Middle East have taken note of Washington’s pivot away from the region and are exploring expanded economic ties with Beijing. In February, the Central Bank of Iraq announced that it would allow trade with China to be settled directly in yuan in an attempt to improve access to foreign currency. The move comes after reports last year indicated that Saudi Arabia was in talks with China about pricing some of its oil sales in yuan. The yuan is still far from being internationalized, and most global trade—especially in the energy and commodity markets—remains dollar-pegged. But a gradual shift toward yuan settlement in the Middle East is a concerning trend. This should give the Biden administration pause before further retreating from the region; while China’s ability to create a parallel financial system that doesn’t rely as heavily on the US dollar is far from a foregone conclusion, even modest steps in this direction could erode the effectiveness of US sanctions globally.

Beijing’s desire to use the yuan as a foreign-policy tool with Middle East partners has extended even into the digital realm. In 2022, the Digital Currency Research Institute of the People’s Bank of China and the Central Bank of the United Arab Emirates, along with two other central banks, launched a pilot through the Bank of International Settlements to develop a prototype for an interoperable wholesale central bank digital currency (CBDC). The project, called mBridge, is exploring whether CBDCs can facilitate inexpensive and immediate cross-border transactions and address frictions in today’s cross-border payment systems. Yet the long-term geopolitical motivations cannot be ignored. Although China’s own CBDC—the digital yuan, or e-CNY—is mainly used for domestic retail payments and is only in its early stages of development, Beijing is laying the groundwork to influence how international standards around digital currencies are shaped, potentially edging out the United States from playing a leading role in this effort.

A legacy at stake

The Biden administration’s shift away from the Middle East is, at least in part, a necessary correction from the Donald Trump presidency—a period in which US fawning over autocrats in the region held Washington back from addressing thorny human-rights and governance challenges. But the pendulum may have swung too far: Washington’s current approach threatens to chip away at a critical piece of its bilateral relationships across the Middle East, undo years of meaningful progress on developing effective counter-illicit finance regimes in the region, and weaken US AML/CFT and sanctions efforts globally.

US national security is dependent on a robust, global infrastructure to protect against illicit finance threats. That infrastructure relies on cooperative action, information sharing, and joint standard setting. Yet as Beijing courts countries in the Middle East with its “no strings attached” approach, there is increasingly less incentive on the part of governments in the region to uphold and enforce US sanctions programs or support counter-illicit finance efforts. It’s a trend that should be deeply concerning for US national-security interests.

In public remarks last month, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said the United States is seeking “healthy competition” with China. But that will take more than enhancing US hard-power capabilities and increasing diplomatic engagement in China’s backyard. To maintain its global leadership position, the United States must adopt a broad strategic effort, both geographically and functionally. In this case, that means remaining engaged with Middle East partners who were main characters in the United States’ alliances in the post-9/11 years. And it means investing in all forms of engagement, particularly economic statecraft.

Otherwise, future US administrations may look back decades from now, wondering how and why partners in the Middle East built stronger bridges to Beijing, leaving Washington without an invite to the majles.

Lesley Chavkin is a nonresident senior fellow with the Economic Statecraft Initiative of the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center and served as the US Treasury Department’s financial attaché to Qatar and Kuwait from 2017 to 2020.

Further reading

Wed, Apr 5, 2023

China is getting comfortable with the Gulf Cooperation Council. The West must pragmatically adapt to its growing regional influence.

MENASource By Joseph Webster, Joze Pelayo

The US and its allies and partners must pragmatically adapt to China’s growing regional influence by providing credible alternatives to Beijing.

Thu, Jan 27, 2022

China is trying to create a wedge between the US and Gulf allies. Washington should take note.

MENASource By Jonathan Fulton

Recent events indicate that leaders in Beijing are no longer satisfied with the logic of strategic hedging and are pursuing a more muscular approach to the Gulf.

Thu, Feb 3, 2022

China may now feel confident to challenge the US in the Gulf. Here’s why it won’t succeed.

MENASource By Ahmed Aboudouh

Despite China’s growing aggressive approach towards the United States in the region, it has no detailed plan to execute it successfully.

Image: US President Joe Biden boards a plane following an Arab summit at King Abdulaziz International Airport, in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, on July 16, 2022. Photo via REUTERS/Evelyn Hockstein.