Intelligence services can be a double-edged sword during peace negotiations. The United States, as it pushes for a political settlement and withdraws its troops from Afghanistan, needs to leave a credible and professional Afghan intelligence partner behind with whom it must partner for counter-terrorism (CT) missions post-withdrawal. Offshoring this crucial sector to Afghanistan’s neighbors will prove disastrous. In a country like Afghanistan, which is overrun with intelligence schemes, operatives, and an ongoing intelligence proxy war mostly waged and supported by its neighbours, the art of intelligence has the final say in battlefield gains and war strategy. Access to information and the quality of intelligence will ultimately define the winners and losers of this war.

Recently, a wave of assassinations, targeted killings, and skyrocketing battlefield casualties have raised alarm bells across Afghan society, including government officials, members of the Afghan security forces, human rights activists, academics, religious leaders, and the ulema. Given the grave implications of these repeated and systematic intelligence failures, there are growing calls for a comprehensive overhaul of the Afghan intelligence services in preparation for a potential peace settlement.

The current failure of the intelligence sector is not surprising. Although the geography and politics of Afghanistan have been intertwined with intelligence and intelligence work for generations—from the time of envoys and emissaries of the British Raj and the court of Russian Czars who were part of influence and counter-influence operations, to dissidents from the Russian, British, and Persian empires who sought refuge in Afghanistan, to Alexander the Great, Timur the Lame, and Hitler’s Gestapo who sent delegations to use Afghanistan as a corridor to infiltrate and challenge each other’s spheres of influence—Afghans themselves have mostly been bystanders, retaining little agency as they either benefitted from or were victimized by these shadowy machinations.

Although this history has made Afghans resilient survivors, it has also made them poor intelligence players, a legacy that continues to have significant repercussions today. In Afghanistan’s war, good intelligence is the difference between victory or defeat on the battlefield. Despite its critical importance, the development and professionalization of the Afghan intelligence services has been largely neglected since the US intervention. As a result, this sector remains the most under-invested and politicized area of the Afghan security landscape, lacking both a professional and well-trained apparatus as well as a clear mandate for domestic and foreign intelligence operations. Afghan security forces, along with their foreign partners and allies, have remained overly reliant on technology and signals intelligence like Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR), with little eyes and ears on the ground. This reality stands in sharp contrast to the highly effective human intelligence and counter-intelligence services of the Taliban.

Although President Ashraf Ghani will be remembered for his resolve and determination to reform the Afghan security sector—as he has taken some bold steps to reform the army and police—the Afghan intelligence community remains classical, obsolete, and in dire need of reform. Now is the time to carefully assess the field, reform the Afghan intelligence apparatus, and lay a strong foundation in preparation for peace.

The Afghan intelligence landscape

Afghanistan is infested with intelligence operatives pursuing various objectives and agendas, most of which are related to counter-terrorism. Most prominent among them are the various American and NATO country agencies, followed closely by those of Afghanistan’s neighbors and other regional countries. All of these actors are vying for dominance and foreknowledge of each other’s activities. While Afghan agencies are also present, they have been mostly concentrated in urban centers and are over-reliant on their foreign partners for resources and guidance.

Afghans need to take back control from the unwanted number of intelligence operatives and players operating on its soil, dominate its intelligence space, and choreograph it in a way that serves its national security interests. This can be achieved through bilateral and multilateral collaboration and partnerships with allies and friendly countries.

The pyramid of institutions and the need for professionalization

Afghan intelligence institutions are organized like a pyramid. At the top of this pyramid sits the National Directorate of Security (NDS), an oversized and over-mandated agency. Next on the pyramid sits the Directorate of Military Intelligence (DMI) and the Directorate of Police Intelligence (DPI), which serve as two separate institutions and quasi wings of the NDS, dealing with military and criminal-civilian intelligence issues. In between these two levels, there are several intelligence sharing centers meant to ensure timely delivery, coordination, and dissemination of intelligence products at the tactical, operational, and strategic levels.

Although the NDS has undergone many reforms and a democratization process, its dark past makes progress difficult. The Soviet-era predecessor of NDS—known as KhAD—was known for arbitrary arrests, disappearances, solitary confinements, and notorious torture techniques learned from its Soviet KGB counterpart. Today, many KGB trained cadres remain. Complicating matters, in addition to these Soviet-era trained officers who comprise the bulk of the personnel, there are at least three other generations of officers operating within the intelligence apparatus, including mujahidin intelligence operatives, civilians who have changed professions, and finally, a new generation of western-trained intelligence officers. All of these groups have been trained in different schools and with different work ethics, intelligence work cultures, and methods of operation. This makes it extremely difficult to cobble together a cohesive force.

Investing in a single professional training infrastructure to prepare future cadres of Afghan intelligence officers to operate as a cohesive force should be a high priority.

Division of labor: Military and civilian intelligence versus domestic and foreign intelligence

Sitting atop the Afghan intelligence agencies pyramid, the NDS is currently overburdened with too many tasks—both domestic and foreign—as it also deals with civilian intelligence matters. Although it has become the center of gravity of all intelligence matters, the NDS lacks the capacity and resources to manage all of its responsibilities.

To make this institution and the Afghan intelligence community more effective and efficient, the entire Afghan intelligence landscape will have to be re-organized. Different bodies will require clearly delineated responsibilities and authorities, all of which should be based on new legal foundations. As part of this re-organization, the Afghan intelligence community needs to establish a separate foreign intelligence agency, given that most of its threats emanate from outside of its borders. Specific agencies dealing with civilian and law enforcement intelligence matters also need to be established.

From intelligence development to policymaking: Fixing incoherent systems and processes

One of the fundamental problems within the Afghan intelligence community is that raw and unprocessed information is often presented as a final intelligence product for policy makers. This has had disastrous consequences, highlighting deep flaws in all stages of the intelligence development cycle from collection to analysis to dissemination.

At present, Afghanistan lacks a streamlined national security structure that rationalizes the intelligence and military products into recommendations and decisions. A lack of differentiation between tactical, operational, and strategic intelligence and their appropriate contexts is clearly evident. This matter is complicated by a dependency on foreign partners for technical and professional assistance, which further impedes matters related to policy development and decision making.

With its defense, intelligence, and foreign policy systems so fragmented and disorganized, Afghan leaders are currently unable to strategically pursue national security interests, and it is not uncommon to observe varying policy positions announced by different national security organs over the same matter. To address this shortcoming, the Afghan government and its allies have established a number of intelligence coordination centers. However, these centers often act as “post offices” rather than effective processing and dissemination centers able to pass information on to policy makers in a timely manner.

The enemies within: Counter-intelligence

One of the main challenges facing the Afghan intelligence community following the US intervention has been the politicizing of its institutions, which are seen as lacking professional integrity. Although this has changed over time in certain sectors, little time and few resources have been devoted to shoring up the capacity and professionalism of counter-intelligence capabilities of the Afghan agencies. Rampant politicizing and a lack of capacity have left many key Afghan institutions prone to infiltration by the Taliban and other regional nonstate actors, with terrible consequences including a plethora of green on green (Afghan military on Afghan military) and green on blue (Afghan military on foreign forces) insider attacks. When these attacks started, both Afghans and their international counterparts struggled to deploy resources to counter them. This gap was not limited to military counter-intelligence and was equally felt across the intelligence services spectrum, including within national security and civilian spheres.

The United States and its NATO allies need to assist and invest in human and technical counter-intelligence capabilities of its Afghan partners specifically considering the risks of terrorists infiltrating Afghan services.

Peacetime intelligence infrastructure for counter-terrorism

Throughout the war, Afghan intelligence services have worked tirelessly to protect and preserve Afghan territorial integrity and sovereignty. They have also played a key role in the global war on terror. With the peace deal on the horizon, the Afghan intelligence community still has an important role to play and needs to begin acting as an enabler of peace rather than a a spoiler. By providing credible intelligence on spoilers and splinter groups on either side of the negotiations, they can play an important role as a catalyst to the Afghan peace process.

Once a peace deal is reached, any post-peace settlement Afghan government, along with its international allies, will need to preserve the professional body and forces of this important sector. It will, however, need to be fundamentally overhauled, re-organized, and modernized to be able to meet the challenges of the post-peace settlement environment. Chief among these challenges will be the process of integrating the Taliban intelligence apparatus into these new reformulated and reorganized institutions.

In addition, the United States and its NATO allies—as traditional partners and foundational allies of the Afghan intelligence community—will have to invest heavily on building up the counter-terrorism capabilities of the Afghan agencies that will serve as credible partners in counter-terrorism efforts after the US withdrawal. The NDS and its sister institutions will need long-term technical and financial support from the United States and NATO allies on this and other areas.

Oversight and democratic control

The current legal framework of the Afghan intelligence apparatus is outdated and must be brought up to date to ensure professionalism, transparency, and accountability. The post-peace Afghan government will need to appoint a commission to undertake the task of fundamentally reviewing, revising, and updating the legal framework and policy foundations of the entire intelligence sector.

The Afghan intelligence community must take this opportunity to shed its dark legacy and rebrand itself as a professional and apolitical sector committed and loyal to the Afghan nation. More democratic oversight will go a long way towards achieving this goal. In this respect, the Afghan parliament and presidency will have an important role to play. Bringing in the right legislation and policy instruments will help to create the appropriate balance between transparency and secrecy in the Afghan intelligence community.

Policy recommendations

The Afghan intelligence community needs to be overhauled and re-organized along these lines with the following five key elements:

- Update the legal and policy framework and foundations of the entire intelligence community of Afghanistan and re-organize the Afghan intelligence sector with clearly defined mandates for all of its agencies. This includes clear delineation of military and civilian intelligence work and domestic from foreign intelligence in the context of the Afghan peace talks and beyond.

- Design and implement a comprehensive investment program on technical capabilities and human resource capacities of the Afghan intelligence community.

- Establish robust and multi-layered democratic oversight of the Afghan intelligence community to ensure civilian and political oversight and hold them accountable for democratic controls.

- Establish a Joint Intelligence Committee of all the intelligence chiefs of Afghanistan under the chairmanship of the Afghan President as the commander in chief for better intelligence sharing, coordination, and decision making at the strategic level.

- Separate domestic and foreign intelligence and establish two separate agencies for these areas.

- Invest substantial financial, human, and technical resources on counter-intelligence capabilities of Afghan institutions through a well-thought-out investment plan.

The United States and its NATO partners cannot and should not outsource counter-terrorism and intelligence operations inside Afghanistan to Afghan neighbors. History has proven that offshoring counter-terrorism missions for Afghanistan has failed miserably, and it simply the wrong national security strategy to pursue. Afghan agencies are capable enough to partner with US and western agencies to tackle terrorism and other geopolitical threats. To do this, they need a robust and multifaceted re-investment and re-branding program to turn into long-term professional intelligence partners for the west and the region.

Tamim Asey is the founder and executive chairman of the Institute of War and Peace Studies in Kabul, Afghanistan, the former Afghan deputy minister of defense, and an expert adviser on the Atlantic Council’s Strategic Dialogues on Afghanistan.

The South Asia Center is the hub for the Atlantic Council’s analysis of the political, social, geographical, and cultural diversity of the region. At the intersection of South Asia and its geopolitics, SAC cultivates dialogue to shape policy and forge ties between the region and the global community.

Related Content

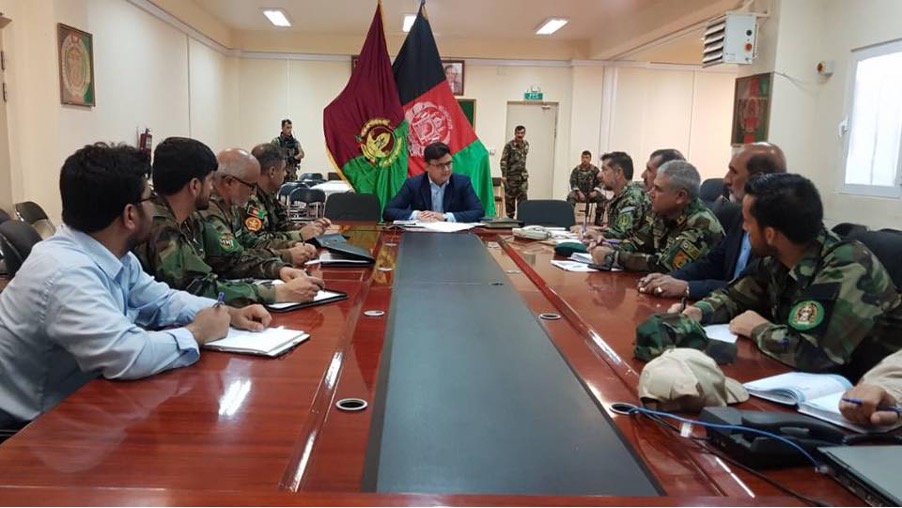

Image: PERSONAL COPY: The author discussing the security and intelligence landscape of southern Afghanistan with members of the Afghan military at the 205th Atal Corps in Kandahar province.