How regime security is set to dominate Saudi-UAE interaction over economic competition and political rivalry

The Visions strategies aimed at diversifying the economies of the Middle East—particularly those of all the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) rentier states—have brought to the fore the divergent objectives of Saudi Arabia’s and the United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) economic policies. These differences are relevant and worth investigating in order to understand the complexity of the relationship. However, in spite of that, it is important to note that the Saudi-UAE relationship can still be considered durable due to shared imperatives surrounding regime security.

One of the primary irritants in their bilateral relations has been oil policy. Saudi Arabia prefers an extended transition towards renewables while the UAE has relatively smaller oil reserves (about one hundred billion barrels, ranking it number six globally). With greater access to sovereign wealth funds, the UAE has gained an advantage in the economic diversification process, although all the GCC states still have some way to go in achieving diversification based on goods and services rather than hydrocarbons and their derivatives. Since Russia was brought into a leadership role alongside Saudi Arabia in OPEC+ in 2016, the UAE has been left with unused oil capacity, which is potentially worth an additional $50 billion annually. This raises questions about the UAE’s membership in OPEC+ and its overall stance towards the kingdom.

Political struggles between Saudia Arabia and the UAE have existed since the founding of the latter in 1971, with territorial disputes and dynastic competition being major facets. About 20 percent of the Shaybah oil field is said to be claimed by Abu Dhabi; the 1974 Treaty of Jeddah failed to sustain a final agreement due to a discrepancy between the oral and the written agreement. This lack of consensus has led to tensions on more than one occasion, especially after President Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan assumed office in 2004 and sought to revive Abu Dhabi’s claims.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, in this new climate, the Dolphin Gas Project—launched in 1999 and envisaged as a pan-GCC project that was later narrowed into cross-border gas transmission from Qatar—was opposed by the kingdom on several occasions. Still, Qatar, the UAE, and Oman were able to begin limited operations in 2007. A proposed 2005 maritime causeway project to link the UAE and Qatar was also resisted, since it would limit Saudi Arabia’s unfettered sea-lane access. It has since come under further doubt due to the prolonged GCC crisis.

Intensifying economic competition

Saudi and UAE economic competition intensified after Saudi Arabia shifted gears in 2016 to pursue its Vision 2030 objectives. Riyadh has introduced a raft of new investment policies, including import rules that exclude goods made in free zones—a key aspect of the UAE economy—and those using Israeli input from preferential tariffs. Other changes include the domicile of regional headquarters and tax breaks.

The Saudi launch of national champions, such as Riyadh Air, is expected to fly to a hundred destinations over the coming years (once operational). It will raise the stakes for the UAE’s flag carriers—Emirates Airline and Etihad Airways—and Qatar’s flag carrier—Qatar Airways—which have been used to feed each respective nation’s tourism industries and bolster their statuses as international hubs. Saudi strategic investments in international sports such as Formula One and golf, as well as megaprojects such as Neom (a planned smart city in Tabuk Province in northwestern Saudi Arabia), will have a similar effect on heightening intra-GCC competition, mostly vis-à-vis Dubai.

Sign up for the MENASource newsletter, highlighting pieces that follow democratic transitions and economic changes throughout the region.

At the same time, the UAE has quickly adapted to changing conditions. It has signed Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreements (CEPAs) that cover many aspects of trade with Israel, India, Indonesia, and Turkey. This contrasts the slower progress of GCC Free Trade Agreement negotiations with major partners, such as the European Union and China.

Additionally, UAE President Zayed has promoted his brother Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed to the position of co-vice president alongside Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid al-Maktoum—thereby consolidating the rule of the Bani Fatima (the six sons of Fatima bint Mubarak Al Ketbi, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan’s most prominent wife). The move also helps to de-personalize the MBS-Zayed leadership dynamic. Given the amount of double hatting—one individual with two different roles—and the amount of crossover between politics and business in the Emirates, this is an important consideration to reduce the potential for bleed-through between politics and economics and vice-versa.

However, there are still likely to be further pinch points pending MBS’ successful rollout of multi-billion dollar megaprojects, such as Neom, the launch and expansion of nascent industries, and whether political consolidation and social engineering prove sustainable.

The preeminence of security concerns

The Middle East has been a critical area of Saudi and UAE interaction and cooperation, especially at the onset of the 2011 Arab Spring, when they activated the GCC’s Peninsula Shield Force (PSF) to respond to the uprising in Bahrain. The PSF guarded key installations, freeing up Bahraini security services to crack down on protesters. Furthermore, Egypt’s Gulf Arab neighbors, along with Kuwait, responded in unison with a variety of economic statecraft in support of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in 2013. This measure was taken after the military seized power in Egypt due to their deep misgivings about the former Muslim Brotherhood-led government and the central role that Qatar had played in Cairo’s political economy.

Given the limitations of GCC cooperation, Saudi Arabia and the UAE formed an informal security alliance in Yemen in 2015 to roll back a Houthi insurgency and restore the internationally recognized government of then-President Abd Rabbu Mansur Hadi. Despite the UAE’s withdrawal from the war in 2019, its legacy continues through ongoing relations with the Southern Transitional Council and influence in the south, including on the island of Socotra and around the Bab al-Mandab Strait and the Red Sea. This protects the UAE’s maritime and commercial interests and gives it further leverage over the future of Yemen. The UAE’s position contrasts with the kingdom’s, which looks set on maintaining Yemeni territorial integrity.

Nevertheless, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are still politically aligned on most issues, including diplomacy with Iran, Turkey, and Syria. There may also be some coordination in theaters, such as in Sudan, where a conflict broke out on April 15 due to an escalating power struggle between Sudan’s de-facto leader and army chief, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) led by General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (also known as Hemedti). Saudi Arabia has taken the lead in mediation given the UAE’s perceived bias in favor of Hemedti.

Fundamentally, it is not economics nor regional politics that are the determining factors in the Saudi-UAE bilateral relationship. Instead, it is the persistent need to maintain regime security during this period of uncertainty that supplants all other concerns and defines the way these two states interact with each other.

Robert Mason is the author of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates: Foreign Policy and Strategic Alliances in an Uncertain World.

Further reading

Mon, Aug 2, 2021

Saudi Arabia and the UAE are economic frenemies. And that’s a good thing.

MENASource By Amjad Ahmad

Both Riyadh and Abu Dhabi have wisely made the economy the focal point of their strategies for the future, as evidenced by national policy changes and a reduction in foreign adventures. Ending the Qatar blockade, and opening a dialogue with adversarial neighbors like Iran and Turkey is linked to long-term economic ambitions.

Thu, Dec 15, 2022

No, Xi’s visit to Riyadh wasn’t because of bad US-Saudi relations. It’s about much more.

MENASource By Jonathan Fulton

Given the bad state of US-Saudi relations, it is natural to see Xi’s visit in the context of geopolitical competition between Washington and Beijing, but that framework misses the bigger picture.

Tue, Apr 26, 2022

Russia’s war in Ukraine is making Saudi Arabia and the UAE rethink how they deal with US pressure over China

MENASource By Ahmed Aboudouh

Ukraine has plenty of lessons about the GCC and China’s growing strategic alignment with the US.

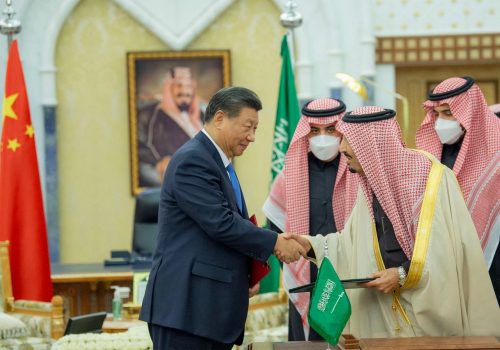

Image: Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman receives The President of the United Arab Emirates, Sheikh Mohammed Bin Zayed Al-Nahyan, in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, July 16, 2022. Saudi Press Agency/Handout via REUTERS