The confirmation of President-elect Joe Biden’s victory was met with deep sighs of relief in European capitals. US President Donald J. Trump’s tenure has traumatized the old continent, and many leaders are looking forward to repairing their relationships with the United States through the next occupant of the White House.

While Western Europe is looking forward to the next four years, the reaction is more mixed as one moves east. Even beyond the countries whose leaders have embraced Trump, such as Hungary, Poland, and Slovenia, Biden’s victory raised questions more broadly for the capitals of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). The reason is simple: The Trump administration—despite (and perhaps because of) its confrontational rhetoric towards Europe and the European Union (EU) in general—intensified cooperation with Central and Eastern Europe.

With Biden’s election, some in CEE fear the return of the years led by former US President Barack Obama, when many believed Washington (initially) sacrificed the region’s interests in the name of a reset with Moscow. The scar is deep. Regional governments warned the Obama administration that Russia was still a threat. In June 2009, leaders such as Václav Havel and Lech Wałęsa sent a public letter to Obama outlining the dangers of resetting relations with Moscow—all to no avail. Some in Obama’s White House (though not Antony Blinken, who was then working for Vice President Biden) were angered by that letter. A few months later, Obama shelved plans for building a missile-defense shield in Central Europe, which led to a major setback in the region’s transatlantic relations. To be fair, it is worth noting that after Russian President Vladimir Putin’s attack on Ukraine, the Obama administration supported a joint NATO-US effort to send troops to Poland and the Baltic states to defend against potential Russian aggression.

Great-power competition in Central and Eastern Europe

As the Trump administration took over in 2017, it placed renewed importance on Central and Eastern Europe, as it recognized that the region was one of the areas where Moscow and Beijing were challenging the US-led global order. The 2017 appointment of Wess Mitchell, whose views on the need to prioritize relations with CEE were very influential, as assistant secretary for Europe and Eurasia at the US Department of State pointed further toward a US pivot framed by renewed great-power competition. The need to compete with a rising China and Russia throughout the globe was also underlined in the 2017 US National Security Strategy and the 2018 US National Defense Strategy.

Active cooperation between the United States and the region began to develop in the fields of diplomacy, security, digital communications, and economics. These new transatlantic ties were not always visible on the surface, but the increasing number of bilateral high-level meetings and the relocation of US military forces to Poland provide some clues. The United States also made a significant commitment to support the Three Seas Initiative (3SI), which aims to bolster cross-border energy, transportation, and digital infrastructure among the twelve countries circumscribed by the Adriatic, Baltic, and Black Seas. Rather than viewing the project as an internal European matter, Washington saw the effort through the strategic lens of renewed great-power competition: It provided an alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative and helped counter Russian efforts to destabilize the region. 3SI has gradually gained support across the US political spectrum, illustrated by a November bipartisan resolution in the US House of Representatives and comments made by longtime Biden adviser (and Atlantic Council fellow) Michael Carpenter.

Biden and Central and Eastern Europe

The Trump administration had some good foreign-policy instincts such as certain steps on China or rapprochement between Israel and Muslim countries. Among them was also this renewed engagement in Central Europe, which Biden should not hesitate to continue. While the mechanism of engagement may need adjusting—perhaps with a broader toolbox—the substance should remain.

Biden’s main partners in Europe will certainly be Berlin, Brussels, and Paris. But this doesn’t mean that the capitals to Berlin’s east should view Biden’s arrival with concern. It is good for Europe as a whole for its main powerhouses to repair their relationships with Washington. But the new administration must also ensure that it doesn’t forget about CEE.

So far, the messages from Biden’s advisers are promising, and the president-elect was among the strongest supporters of the region’s accession to NATO when the US Congress discussed the issue in the 1990s. Biden was also Obama’s interlocutor with the Balkans, Central Europe, and the Baltics, so he understands the issues at stake. But the most encouraging signal of continued US engagement in the region is that the Biden administration seems set to continue to focus on great-power competition. Geopolitics will not go away under the new administration.

While Biden may prove to be tougher on Moscow and less pointlessly adversarial with Beijing, the broad contours of US policy towards these competitors will likely remain the same. The Biden administration is unlikely to return to the fallacy that China’s economic integration means the country is headed for a political and strategic convergence with Europe, the United States, and Asian democracies. CEE countries should also welcome a more principled and assertive US approach on Russia. More digestible rhetoric on China, without giving up the pressure, would make it easier to broaden transatlantic cooperation in this field, as many Europeans are progressively waking up to the challenge coming from Beijing. Diversification of supply chains from China may help CEE manufacturing, which some of the region’s governments now appreciate.

Energy, and in particular nuclear power, will likely be a focal point for the United States in the years ahead as Beijing and Moscow attempt to use this area to increase their influence in Central Europe. China and Russia are bidding—alongside the United States—for contracts to build new nuclear reactors. In 2014, the Hungarian government opted, without a proper tender, for Russian state-owned company Rosatom to expand its Paks nuclear plant with two water-water energetic reactors (VVER). In the Czech Republic, there’s an ongoing debate over whether to allow Russian and Chinese companies to compete for new reactors at the Soviet-built Dukovany power plant. The Russian proposal is expected to be technically and financially competitive, but Czech security and intelligence analysts warn against such a long-term energy marriage. They recently scored points when the government announced that it would postpone the tender to the period after the fall 2021 elections. Poland seems to have already picked the United States to become its major partner for building six to nine nuclear reactors. Washington is also close to sealing agreements on nuclear-energy cooperation with Romania and a few other countries, although those agreements are mostly non-binding. Russia and China’s contest here is far from over. Nord Stream II will of course also be a problem, but given the anticipated strengthening of US-German ties, this issue may be treated more delicately in the years ahead.

The Trump administration’s pivot to CEE didn’t avoid controversies. The president himself occasionally referred to former US President George W. Bush’s dichotomy between the old and the new Europe, though he had no interest in cultivating special ties with nationalist governments. For some in the Trump camp, and perhaps the president himself, cooperation with Central Europe was partly motivated by an ideological affinity for the Hungarian and Polish governments and by a desire to use CEE as a wedge against the EU. Biden seems to be the right person to be able to fix some of the hostile, damaging rhetoric from Trump about the EU and bring relations here to a higher level. On the one hand, he should maintain some of the positive elements of Trump’s policy toward Central Europe, but he’ll need to balance these with his more values-based approach. He is thus likely to bring to Central Europe a new policy blend bridging Obama’s “values promotion” with Trump’s “security commitments.”

The region’s homework

Even in the case of such an appropriate policy blend, however, Central Europe must do its part. There are two crucial conditions for success: The first is related to the region’s behavior, and the second relates to Europe as a whole.

Biden will view his partners through the lens of shared liberal values—such as democracy, human rights, and rule of law—in contrast to the transactional and realist approach of Trump. Therefore, some countries—in particular, Hungary and Poland—might attract undesirable attention from the new administration when taking steps widely perceived as confronting liberal democratic principles.

It’s up to the region, not the United States, to decide which way this will be resolved. The upcoming US administration seems to be ready to turn the page, despite the fact that Budapest, and to a lesser extent Warsaw, made an open bet on Trump. The future course of relations will depend on how these capitals engage with the new administration and how they respond to key value-based expectations from Washington.

Warsaw, utterly transatlanticist, should have less of a problem. Indeed, outreach has already been made to the Biden transition team. Strong opposition voices in Poland are calling on Biden to opt first for a conciliatory approach and motivate the government in Warsaw to grant concessions where they are most needed. Hungary may be a bigger question mark, especially if Budapest continues to push against US interests in certain foreign-policy areas (e.g. the Paks nuclear-power plant or NATO engagement with Ukraine and Turkey) without constructive outreach more broadly.

If some regional capitals choose a confrontational approach, it may present challenges for the region as a whole. Washington likes to categorize and its busy diplomats often prefer to deal with smaller countries grouped into regional blocs. The troubles of a single Visegrád Group (V4) country can therefore potentially cripple the effectiveness of the group as a shared diplomatic tool. This is worth bearing in mind as each country pursues bilateral relations with the new administration. These ties should be rooted in politics based on shared values. Should problems occur, other V4 countries would have to make an extra effort and create a counter-narrative, not by pointing out the neighbor but rather by becoming proactive role models and showing that politics based on shared values works. Those from the region who are ready to use the “power of example”—to quote Biden’s victory speech—will conversely, however, need effective support. This is the space for EU and US involvement.

The second important condition to get Biden’s presidency right applies more generally to Europe. While Biden’s victory—coupled with his subsequent nomination of Blinken, a Europeanist and defender of transatlantic relations, for secretary of state—has placed European capitals at ease, there is the danger that Europe could waste the opportunity to reinvent itself. Europe can’t continue as if the Trump era did not exist. Look around: Voices that are challenging European values—at home and abroad—are still gaining ground. Biden’s presidency is a four-year-wide window of opportunity to push back against them and work to counter future populist mandates.

The entire US political landscape will be transformed by an unprecedented combination of the three major crises in the country (health, economic, and social) and challenges for the US abroad. In the next election, Europe may not get the type of Democrat it has grown used to. Europe knows little about Vice President-elect Kamala Harris and vice versa; future candidates may continue this trend. Europe, and within that Central Europe, must seize the opportunity presented by Biden’s presidency to strengthen ties and at the same time become more autonomous.

In the mother tongue of Europe’s political culture, Biden’s victory could be described as a pharmakon. The Greek etymology here points to both the remedy and the poison. The actual meaning depends on the perspective, on how Europe will administer Biden’s pharmakon. European administrations should apply it in a proper way, take it seriously, and become more active, responsive, and responsible—or the damage of the last four years will become more permanent, including for the central part of the continent.

Petr Tůma is a visiting fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Future Europe Initiative.

Further reading

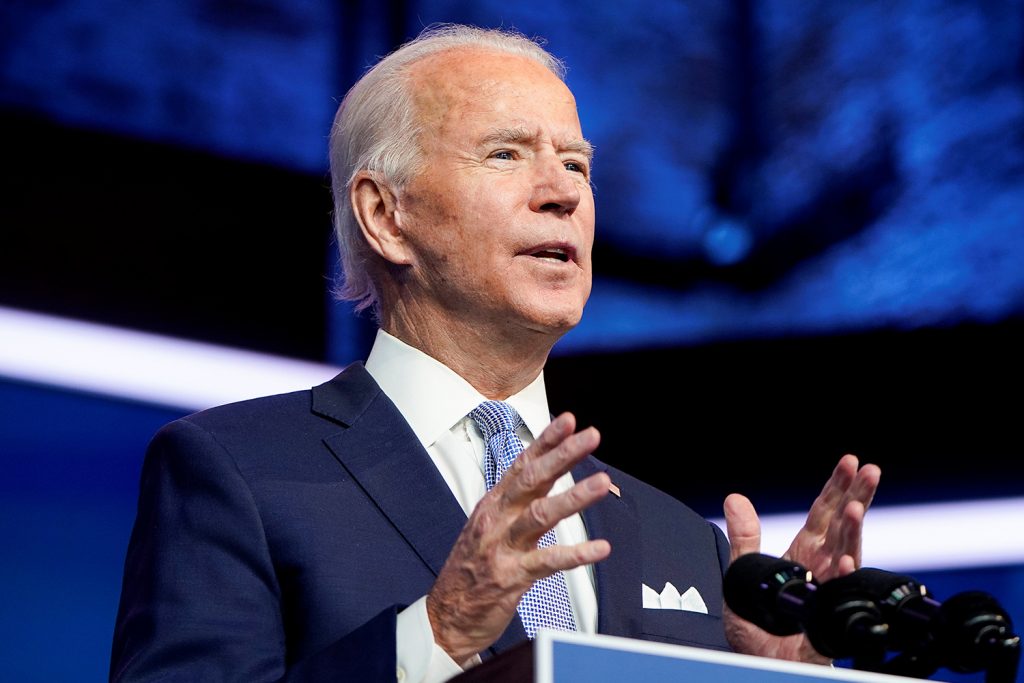

Image: REUTERS/Joshua Roberts