On December 4, 2020, Dhaka followed through on its promise to move refugees from Cox’s Bazar to Bhasan Char, starting a new, unpredictable chapter in the Rohingya crisis. Nearly 2,000 families have been relocated already, and upwards of 100,000 refugees are estimated to be sent to the islet by the end of this year.

The relocation, which was supposedly initiated to address overcrowding in Kutapalong, drew widespread condemnation from rights groups, and with good cause. Till date, United Nations (UN) officials have not been granted access to conduct independent technical assessments and journalists have been barred from speaking to refugees. Although officials maintain that refugees were consulted before being relocated, testimonies indicate that consent was uninformed at best, if not outright coerced.

The islet of Bhasan Char, fifty miles away from Kutapalong, is remote and flood prone. Until a few years ago, the only inhabitants on the islet were nomadic herders and bands of pirates who roamed the nearby waters. Since 2018, however, Bangladesh has invested almost $350 million to make Bhasan Char habitable; it has constructed concrete shelters, erected a flood protection barrier, ensured fresh water supply, and increased military presence in the area. In response to the accusations of the islet being akin to a “prison,” Bangladeshi Foreign Minister AK Abdul Momen recently called Bhasan Char a “beautiful resort 100 times better than the camps.”

While comparisons to resorts might be far fetched, Momen is not entirely wrong. In Cox’s Bazar’s squalid camps, life for refugees remains crippled. A recent report by Asia Foundation found that nearly three in four refugee households are currently in debt from loans they had taken after arriving in Bangladesh. In recent months, gang violence over control of a burgeoning drug trade has killed at least seven, and forced hundreds of families to flee their shelters. Mired in precarity, refugees are falling prey to the lure of smugglers and traffickers, who promise a way out of debt and joblessness.

However, Bhasan Char does not solve these problems as much as it relocates them. Separating some refugees from others does not address the underlying drivers of crime within the refugee camps. If anything, relocation splinters aid response, and further attenuates humanitarian space.

In particular, housing aid-dependent communities in an islet puts humanitarian actors in an unenviable position. Should aid agencies provide relief to refugees and risk legitimizing a move decried by rights groups, the United Nations, and the United States? The United States remains the most generous financial donor to the Rohingya crisis response, and the incoming Biden administration is already being lobbied to take a more active role in the crisis. As it stands, Dhaka has enlisted 22 domestic NGOs to provide basic services, although significant doubt remains on whether these organizations will be able to raise enough funds to fulfill their mandate. Speaking on condition of anonymity, an aid worker told me that,“the provision of services abets long-term displacement and raises ethical debates whether agencies not doing so would lead to more death, conflict, and violence in the short term.”

Importantly, Bhasan Char signifies a disconcerting shift in Bangladesh’s response to the refugees with long-term implications. Three years later, the crisis in Cox’s Bazar has progressed from an acute emergency to that of prolonged displacement. In the camps, a relatively young Rohingya community wants access to employment and education— children want to be able to go to schools and adults want access to jobs. There is an increasing demand for local participation to inform the design and implementation of effective inter-sectoral programming. Simply put, the Rohingya want to have a say in the decisions that shape their lives. On the other hand, confronted with a costly project of little political value, Dhaka’s response looks increasingly aligned toward protecting the interests of the state irrespective of the needs of refugees. The fencing in of the camps, the regulation of mobile connectivity, the relocation of refugees to Bhasan Char— these actions constitute a statement of intent: the Rohingya can stay, but on Bangladesh’s terms.

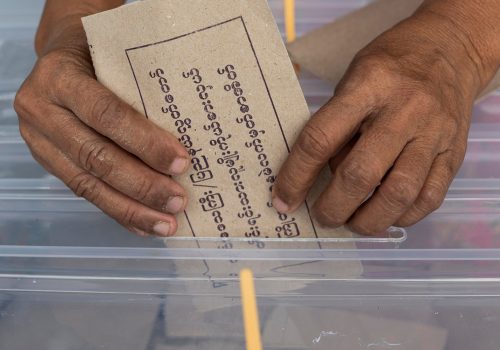

For the one million Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, this translates to having their lives suspended in a web of apathy, injustice, and bureaucracy. Three years on, Bangladesh maintains that repatriation of refugees is the only acceptable solution to the refugee crisis. Increasingly, this seems to be a position based on belief, not evidence. Indeed, despite an injunction by the International Court of Justice, genocide continues in Rakhine, and the recently concluded elections were marred by overtones of anti-Rohingya animus. All the evidence on hand points to an inconvenient truth: for the foreseeable future, the Rohingya will remain in Bangladesh.

To ensure that the Rohingya stay with dignity, a responsive situational approach needs to be adopted that centers the needs, demands, and preferences of the refugees. Basic rights— education, healthcare, movement— need to be protected, not curbed. Synergies between aid and development need to be encouraged, not stifled. Aid dependency needs to be reduced in favor of the economic empowerment of refugees. While Bangladesh has legitimate security concerns linked to the refugee camps, restrictive policies— relocation included— are counterproductive to addressing such risks and could be detrimental to its own interests in the long run.

A more holistic refugee response requires money, of which $600 million has already been pledged. But it also necessitates that the money be spent wisely. In this case, a whole of society approach might prove useful, whereby the host community in Teknaf and Ukhiya are included as active beneficiaries of developmental projects in the region. However, none of this will happen unless common sense policy that responds to evidence and need, rather than shortsightedness and fear, is adopted.

Imrul Islam holds an M.A in Conflict Resolution from Georgetown University and works at The Bridge Initiative in Washington, DC.

The South Asia Center is the hub for the Atlantic Council’s analysis of the political, social, geographical, and cultural diversity of the region. At the intersection of South Asia and its geopolitics, SAC cultivates dialogue to shape policy and forge ties between the region and the global community.

Related Content

Image: Rohingya refugees sit on wooden benches of a navy vessel on their way to the Bhasan Char island in Noakhali district, Bangladesh, December 29, 2020. REUTERS/Mohammad Ponir Hossain