As tensions escalate in the Eastern Mediterranean, Turkey is widely viewed as the troublemaker, apparently grabbing oil and gas in Greek and Cypriot waters in a “neo-Ottoman” quest for lost glory. Athens and Nicosia have described Ankara’s actions as clear-cut violations of international law, which require Turkey to be punished. France has quickly jumped in to support Greece and Cyprus, not only diplomatically but militarily too. The legal picture, however, is more nuanced. Germany recognizes that the situation merits mediation between Greece and Turkey. France, Greece, and the rest of the EU should embrace this approach, and be willing along with Turkey to make serious concessions. One major area of compromise may need to be Cyprus. If the dispute there remains unsolved, it will remain a regional flashpoint and threaten a comprehensive Greece-Turkey rapprochement.

During a September 10 summit of the EuroMed7 on Corsica, French President Emmanuel Macron and his fellow leaders of Greece, Cyprus, Malta, Italy, Spain, and Portugal noted in their closing statement their “full support and solidarity with Cyprus and Greece” against Turkey’s “confrontational actions,” while urging Turkey to end “unilateral and illegal activities” in the Eastern Mediterranean. Macron went even further on the eve of the summit, arguing, “We Europeans need to be clear and firm with the government of President [Recep Tayyip] Erdoğan, which today is behaving in an unacceptable manner,” and that Turkey was “no longer a partner in the region,” although he would like to “restart a fruitful dialogue” with Ankara.

Macron has repeatedly taken offense in recent months when Turkey has failed to toe France’s policy line in Syria and Libya. In Syria, Turkey’s military operation in the north set off alarm bells in Paris and Washington, but blocked the advance of Russian and Syrian forces in Idlib who had been targeting civilians indiscriminately. In Libya, Turkish military support forced Russian mercenaries and insurgents led by the warlord Khalifa Haftar, whom France has supported, to retreat from the outskirts of Tripoli back to eastern Libya, protecting the UN-recognized Government of National Accord (GNA). While containing Russian adventurism is a top NATO goal, Macron nevertheless lamented in late August that “Turkey’s strategy in the past few years was not the strategy of a NATO ally.”

When it comes to maritime boundary disputes in the Eastern Mediterranean, the French president is taking a similar approach. But as Macron reflexively echoes Greek and Cypriot condemnation of Turkey and ratchets up tensions, he seems to be ignoring an important international legal provision that calls for equitable resolutions of disputes over exclusive economic zones (EEZs).

The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) defines an EEZ as a coastal state’s self-declared area above its continental shelf in which it enjoys exclusive rights to develop marine resources, including on and under the seabed, up to a maximum of 200 miles from the coastal state’s shoreline, including islands. This is not to be confused with a territorial sea, which UNCLOS defines as a state’s sovereign territory on the seabed, sea surface, and the airspace above, which can extend to a maximum of twelve miles from shore.

Countries unilaterally declare their own EEZs and then register them with the United Nations. Inevitably, disputes arise among neighboring states when their respective EEZ claims overlap. Article 59 of UNCLOS stipulates that such conflicts “should be resolved on the basis of equity and in the light of all the relevant circumstances, taking into account the respective importance of the interests involved to the parties as well as to the international community as a whole.”

For the past few decades, Greece and Turkey have been trying to work through their conflicting maritime claims in the Aegean Sea in pursuit of an equitable solution, though not without acrimony. They have agreed that Aegean islands will have no EEZs, despite the 200 miles allowed under UNCLOS, so that Greek islands lying just off Turkey’s coast will not deny Turkey any EEZ throughout much of the Aegean. At the same time, Athens has indicated that it might unilaterally extend its Aegean islands’ territorial seas from the six miles allowed prior to 1982 under international law to the twelve miles permitted under UNCLOS. Ankara, which has not signed onto UNCLOS, warns that any such move would constitute a cause for war.

Greece and Turkey have found even less common ground on their dispute over Kastellorizo (or Meis in Turkish), a tiny Greek island located far to the east of the Aegean that hugs Turkey’s Anatolian coast. Athens insists Kastellorizo enjoys a full EEZ of 200 miles, in accordance with UNCLOS. As the map below indicates, this approach results in a massive EEZ for Kastellorizo, leaving Turkey, the country with the longest coastline in the Eastern Mediterranean, with one of the region’s smallest EEZs.

Rejecting this outcome as unreasonable and unfair, Turkey argues that only a country’s mainland can generate an EEZ, while islands cannot. Ankara thus calls for bilateral negotiations with Athens to reach a “reasonable” solution. An official statement by the Turkish Foreign Ministry’s spokesman on July 22 summed up his government’s frustration: “The argument that an island of ten square kilometers, located only two kilometers away from Anatolia and 580 kilometers from the Greek mainland should generate a continental shelf area of 40,000 square kilometers is neither rational nor in line with international law.” Athens, however, has generally rejected such talks.

While President Macron staunchly supports the positions of Greece and Cyprus, German Chancellor Angela Merkel stepped into the diplomatic breach in July, convincing President Erdoğan to suspend exploration for oil and gas just south of Kastellorizo by Turkey’s national oil company, TPAO, in exchange for Athens’s agreement to negotiate with Ankara over conflicting EEZ claims there. Germany then facilitated several meetings among senior Turkish and Greek officials, who agreed to reinvigorate their dialogue.

On August 6, however, hours before release of a joint statement about this new round of talks, Greece announced that it had signed a maritime-boundary agreement with Egypt that conflicts with Turkey’s claims. This agreement, in turn, was in response to a November 2019 maritime-boundary delimitation accord between Turkey and Libya according to which Turkey expanded its EEZ claim significantly at Greece’s expense by denying an EEZ for Crete (as well as Rhodes). Crete carries particular emotional weight in Greece, being the country’s largest island, the mythical birthplace of Zeus, and the center of Europe’s first civilization, the Minoans.

Turkey responded to the Greece-Egypt agreement by restarting TPAO’s exploration activities near Kastellorizo, under escort by Turkish Navy warships. Greek warships regularly shadow them, while French and Greek warplanes conduct joint military exercises in the area. In mid-August, a Greek warship collided with a Turkish Navy vessel escorting TPAO’s seismic-survey ship, Oruc Reis. Meanwhile, President Erdoğan warned on September 5 that Greece (and Cyprus) “will understand that Turkey has the political, economic, and military strength to tear up immoral maps and documents….They will either understand the language of politics and diplomacy, or on the field through bitter experiences.” Erdoğan added ominously, “We are ready for every possibility and every consequence.”

Stemming this dangerous action-reaction cycle requires urgent international mediation. The European Union is reportedly preparing such an effort, which will include both positive incentives and tough new sanctions on Turkey should talks fail. NATO has also started talks between Turkey and Greece on military deconfliction in the Eastern Mediterranean.

An initial de-escalatory goal of EU-led talks could be for Turkey to extend indefinitely TPAO’s September 12 suspension of Oruc Reis’s exploration near Kastellorizo and perhaps recognize the special case of an EEZ for Crete in exchange for Athens accepting no EEZ for Kastellorizo.

Were Ankara to agree to some sort of special economic rights for Crete, it would mark a major concession, breaking with Turkey’s longstanding position that islands are not entitled to EEZs. Eliciting such a concession will require Greece to agree to Turkey’s insistence on discussing the “full range of issues” dividing them in the Eastern Mediterranean. Chief among these is Cyprus, where Turkey has not legally recognized the Government of the Republic of Cyprus since 1974. UN-led mediation between the Government of the Republic of Cyprus (supported by Greece and a member of the EU) and the Turkish Cypriot community (supported by Turkey) has so far been unsuccessful in reuniting the island.

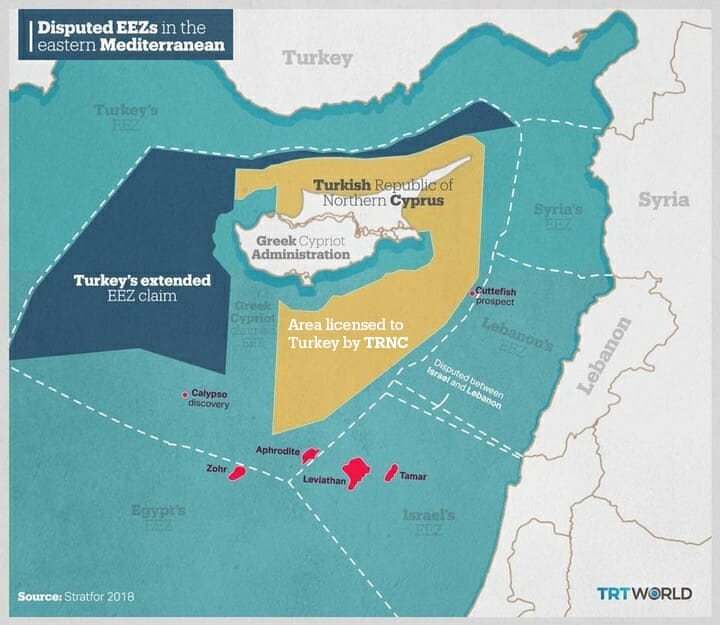

This political division of Cyprus results in competing EEZ claims as depicted in the map below.

The Greek Cypriot authorities in Nicosia, who are the internationally recognized government of an EU member state, claim an EEZ that surrounds the entire island, and which is defined by delimitation agreements with Egypt in 2003, Lebanon in 2007, and Israel in 2010. Nicosia subsequently licensed several hydrocarbon-exploration blocks to international oil companies in waters south of the island. These companies began seismic surveys and drilling in 2011. In response, Turkey and the Turkish Cypriot leaders signed a maritime-boundary delimitation agreement in 2011, resulting in their own EEZ claims and licensing hydrocarbon-exploration blocks in waters also claimed by Nicosia.

The Turkish government maintains that it showed restraint by refraining from any challenges at sea to the above actions by Nicosia from 2003 to 2011. Moreover, TPAO waited an additional seven years to begin drilling, helping provide space for the latest round of UN-brokered talks aimed at reunifying Cyprus in a bi-zonal, bi-communal federation. Those talks collapsed, however, in the summer of 2017 and TPAO started drilling a year later.

The political, economic, and legal disputes dividing Cyprus long predate current tensions between Turkey and Greece over Kastellorizo and Crete, and will require an intensive and sustained diplomatic effort by the EU and perhaps the United States to prevent crises from recurring in the Eastern Mediterranean.

France, Greece, and the entire EU should embrace this de-escalatory approach, recognizing that the entire transatlantic community will be strategically better off with a strong Greece-Turkey relationship that ensures a fair system for sharing Eastern Mediterranean energy resources.

Matthew Bryza is a senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center. He served as a US diplomat for over two decades, including as US ambassador to Azerbaijan and deputy assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasian affairs. He is also the CEO of Lamor Turkey, a Finnish-Turkish joint venture providing environmental solutions, and a board member of Turcas Petrol, a publicly-traded Turkish energy company invested in gasoline stations (with Shell), electricity generation (with RWE), and geothermal power.

The views expressed in TURKEYSource are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

Further reading:

Image: Greece's Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, Italy's Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte, Cyprus' President Nikos Anastasiadis, France's President Emmanuel Macron, Portugal's Prime Minister Antonio Costa, Spain's Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez, and Malta's Prime Minister Robert Abela pose after the closing of the seventh MED7 Mediterranean countries summit in Porticcio, on the Mediterranean Island of Corsica, France September 10, 2020. Ludovic Marin/Pool via REUTERS